Close

+

Fisheries

+

Silica Sand

+

Phosphate Rock

+

Carbon

HREEs

LREEs

Germanium

Borate

Strontium

Natural Graphite

Bauxite

Indium

Lithium

Coking coal

Flourspar

Baryte

Gallium

Hafnium

Tantalum

Silicon

Phosphate rock

Natural rubber

Titanium

Vanadium

Antimony

Bismuth

Berylium

PGMs

Cobalt

Tungsten

Scandium

Phosphorous

Niobium

Magnesium

Supply risk

Economic importance

↓

Research

…

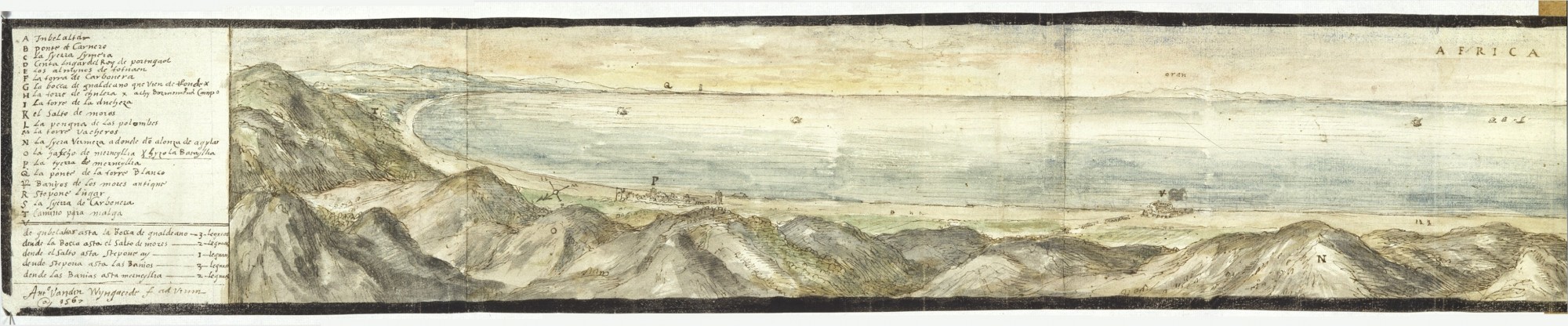

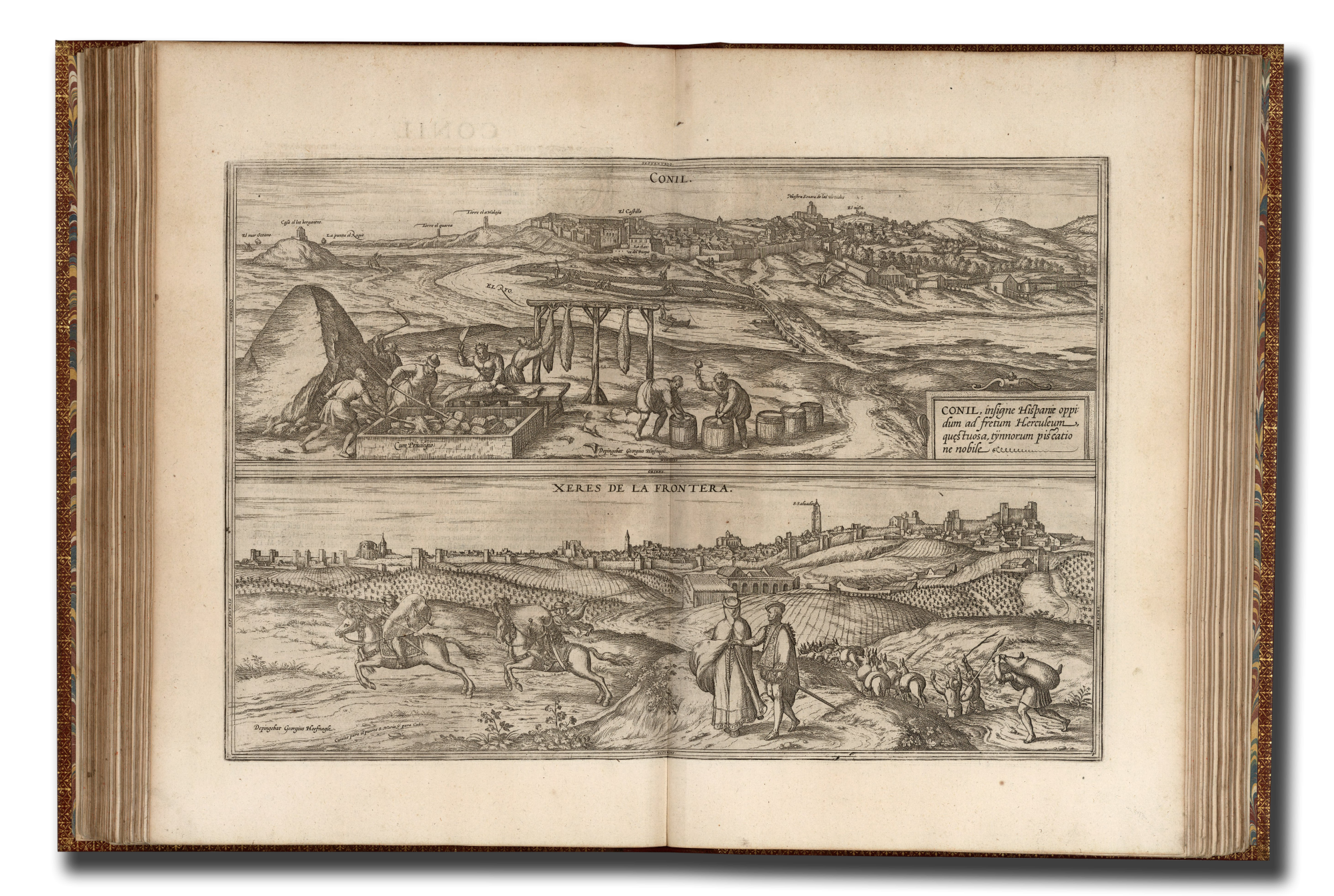

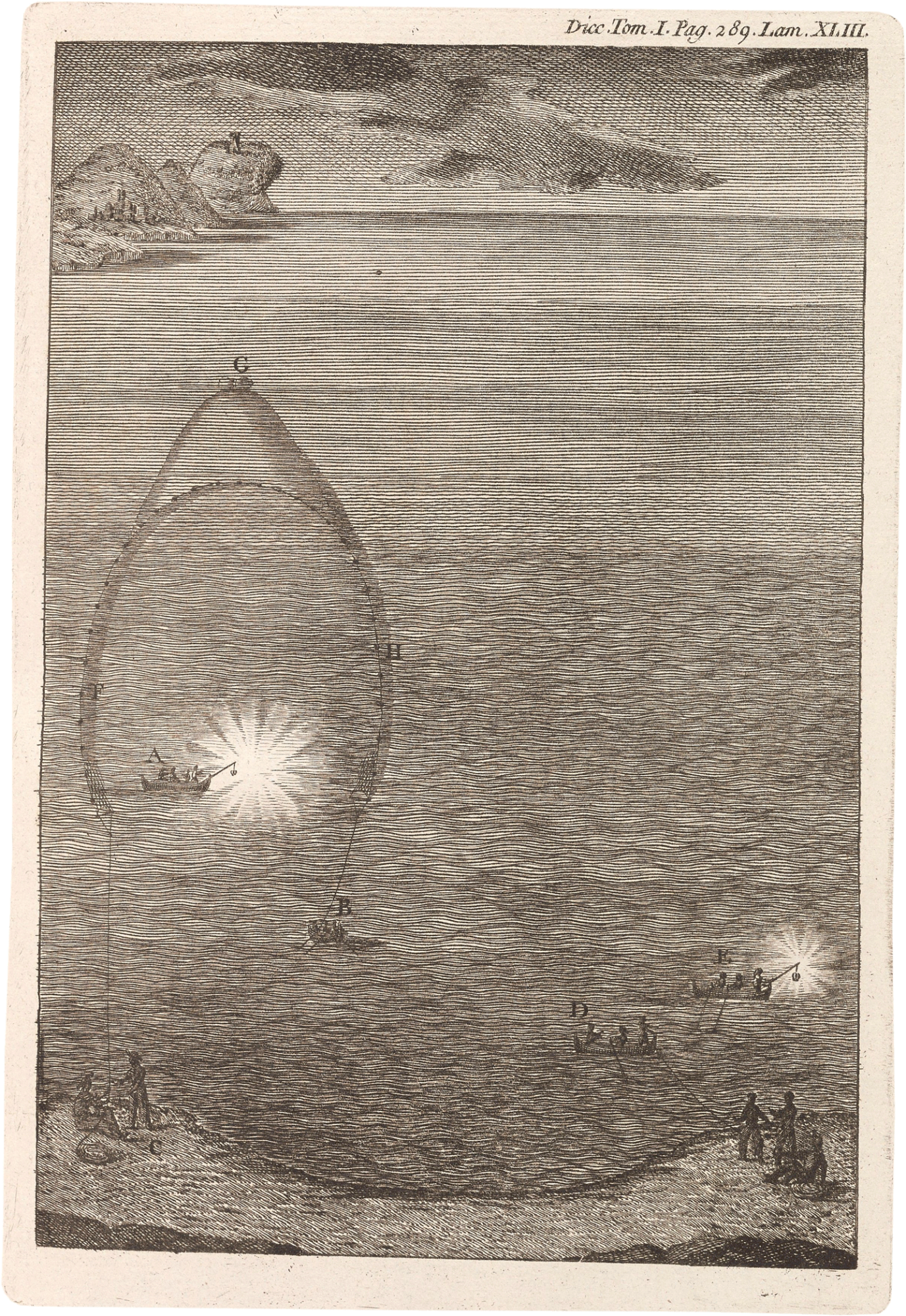

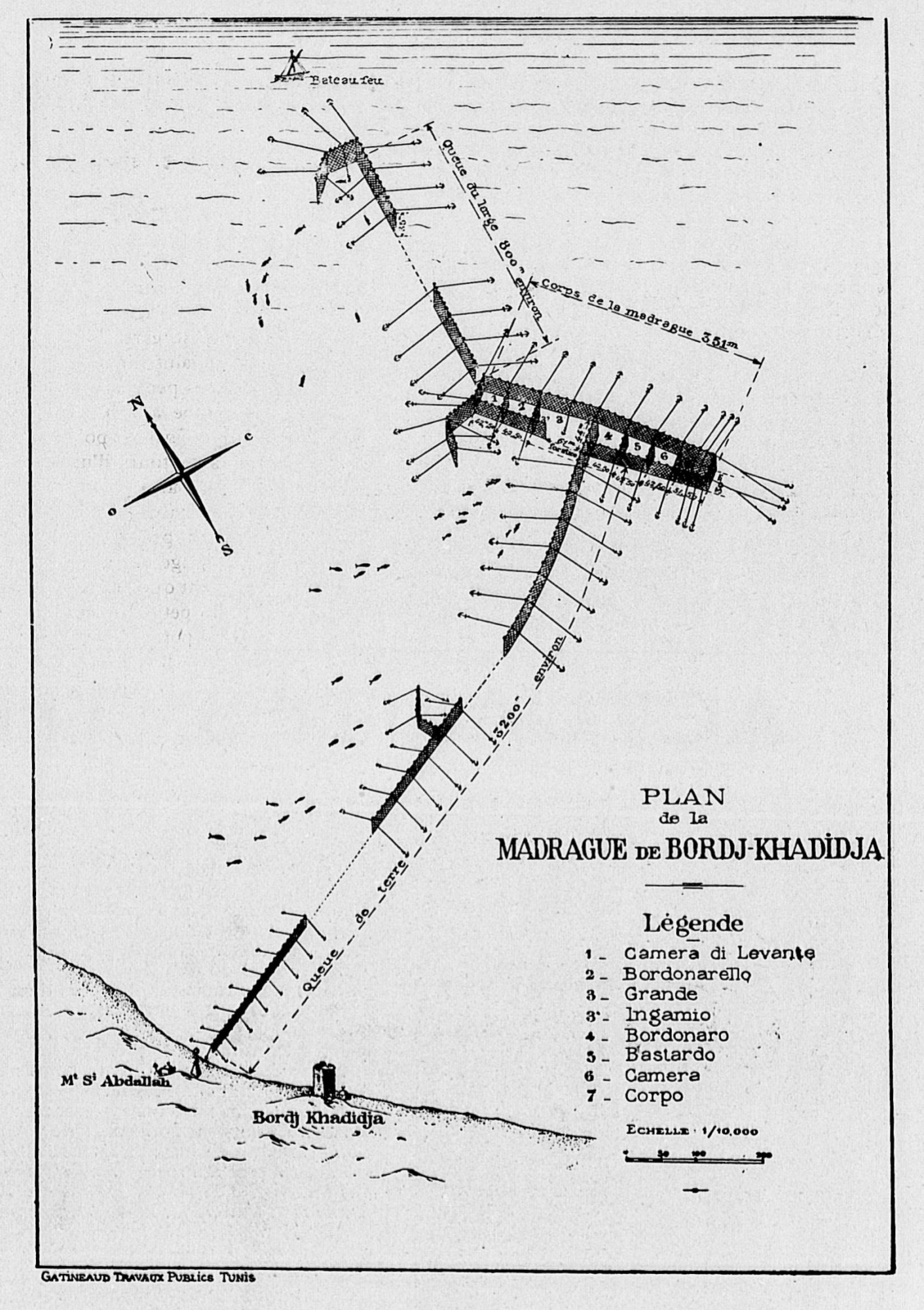

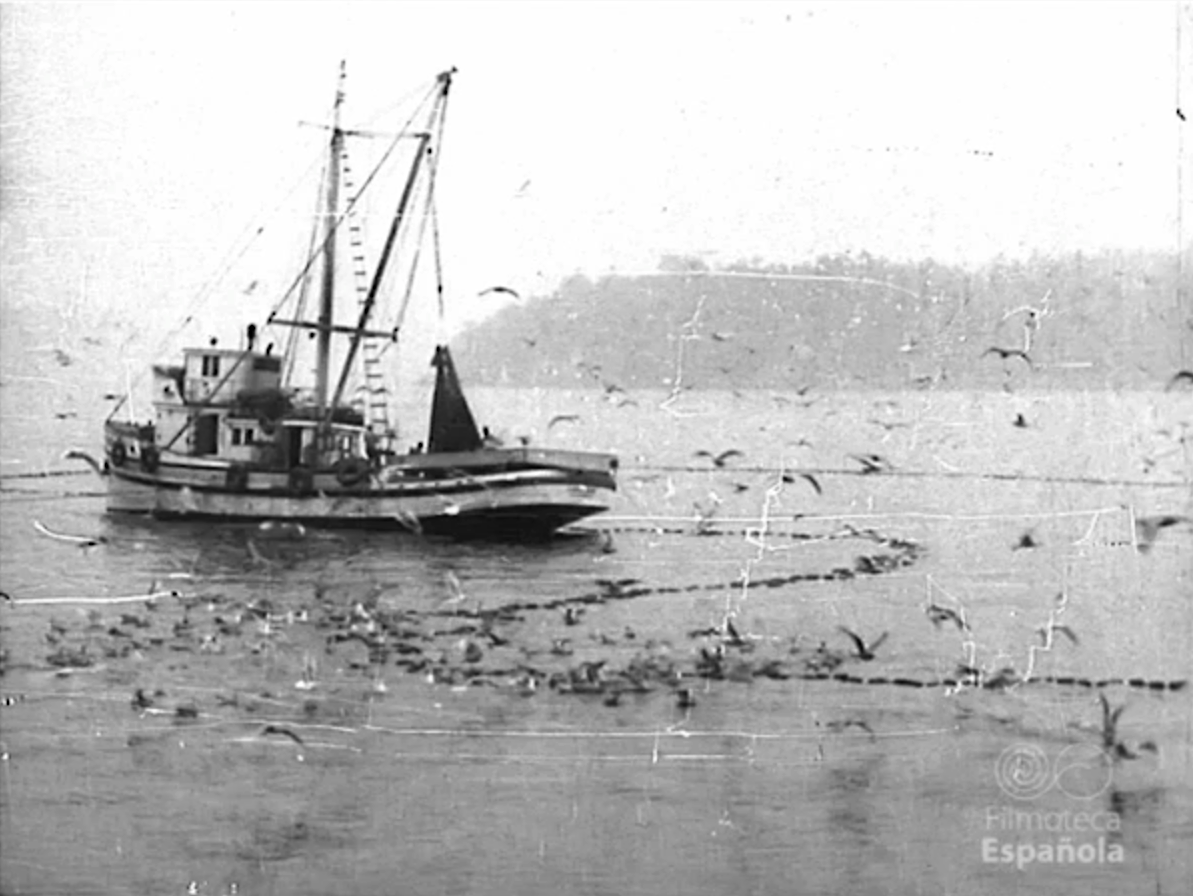

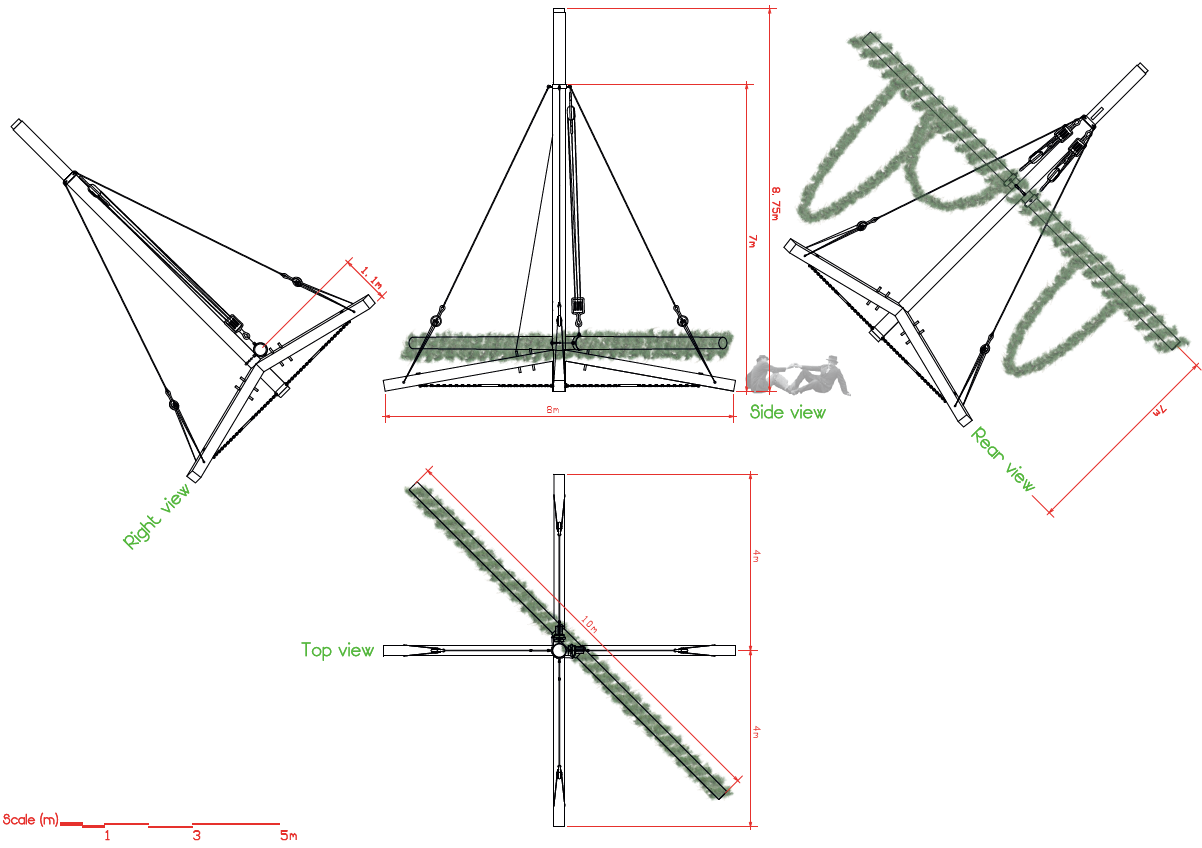

Tuna Watch Tower

Tuna Watch Tower

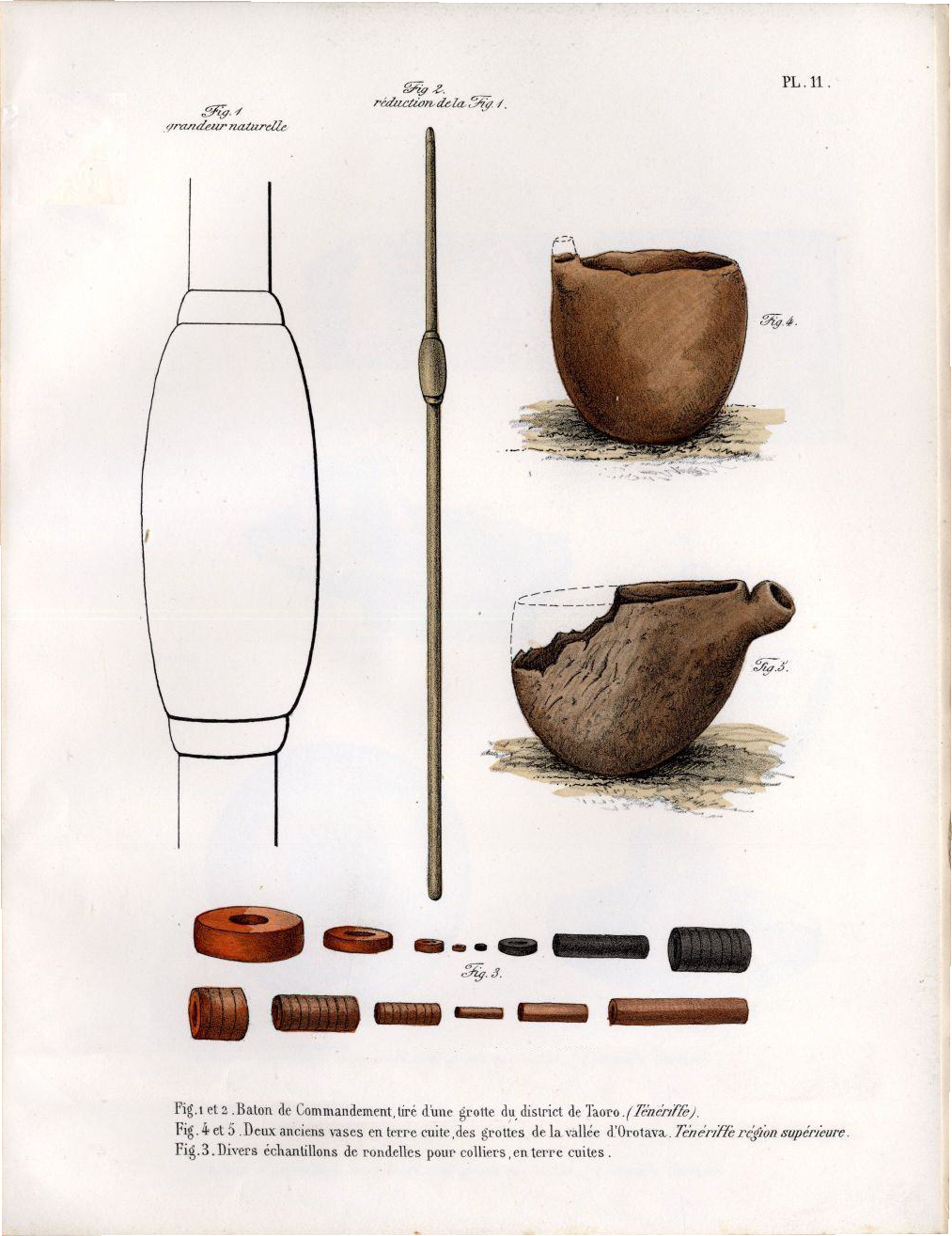

In the 16th century, the Duke of Medina Sidonia ordered the construction of towers with a dual function besides safeguarding: lookouts to aid pelagic fisheries such as anchovy, sardine, mackerel, or tuna. Such towers allowed the sighting of migratory species based on the ability to distinguish target species schools, either by the dark tone on daylight — pesca a la color — or by phosphorescence radiated by fish banks radiate at dark — pesca al arda or ardentía. Land and water crews were alerted with the use of flags and/or smoke in order to coordinate the kettling of fish schools into traps whose fishing rights were an exclusive monopoly of the duchy.

…

Genealogy

Genealogy

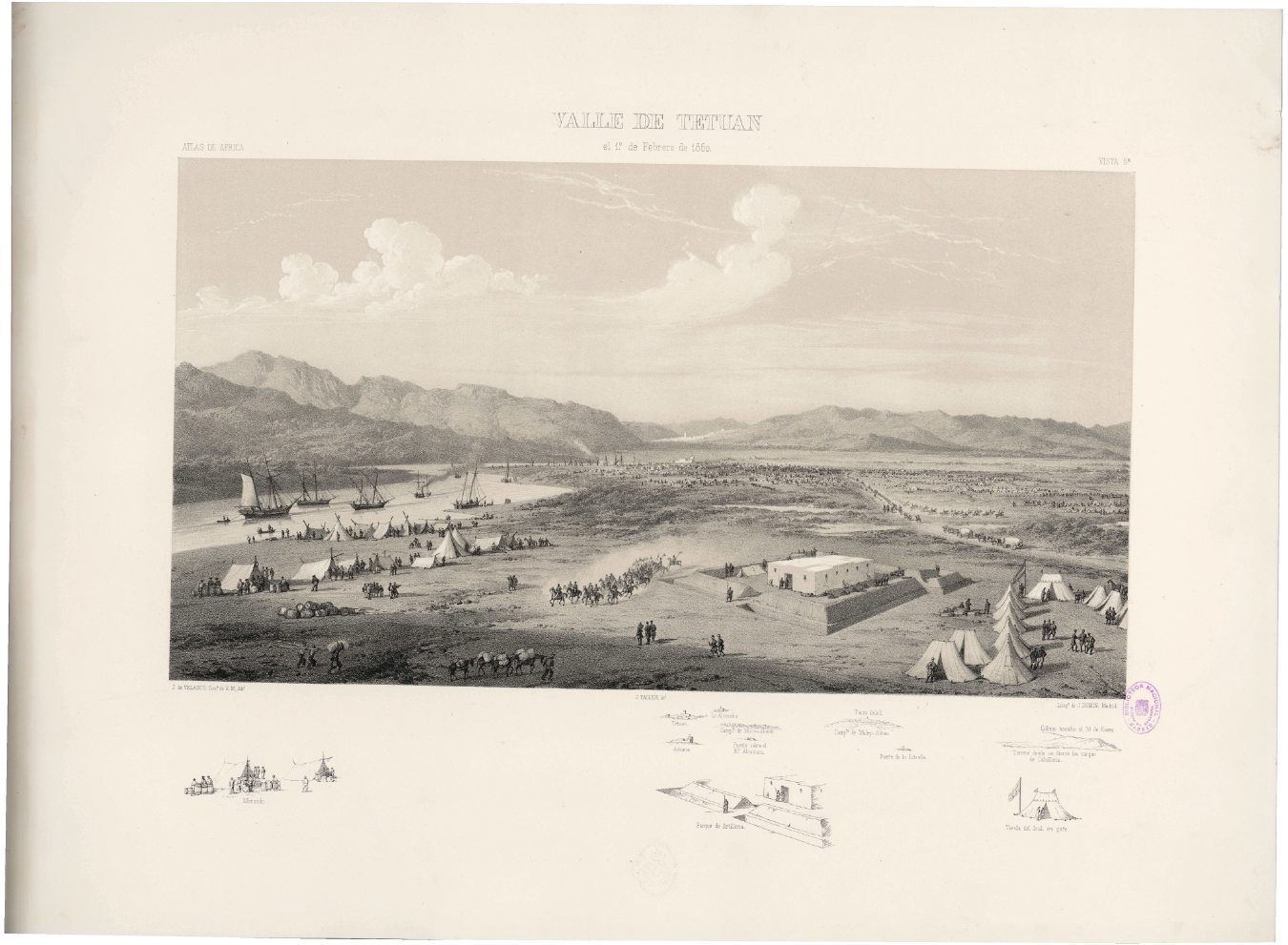

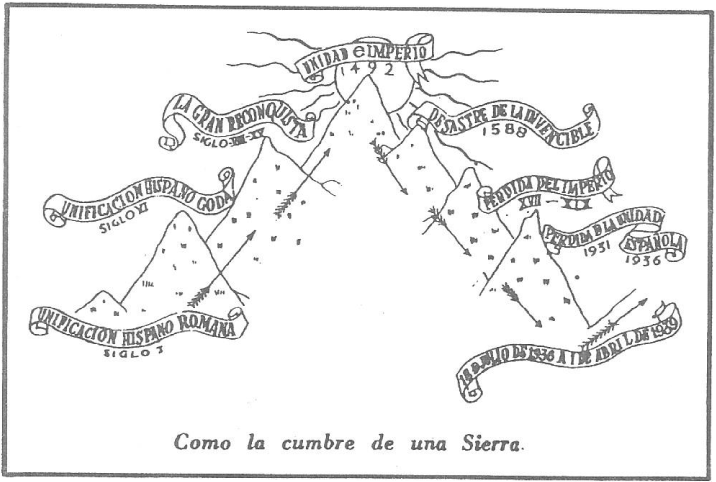

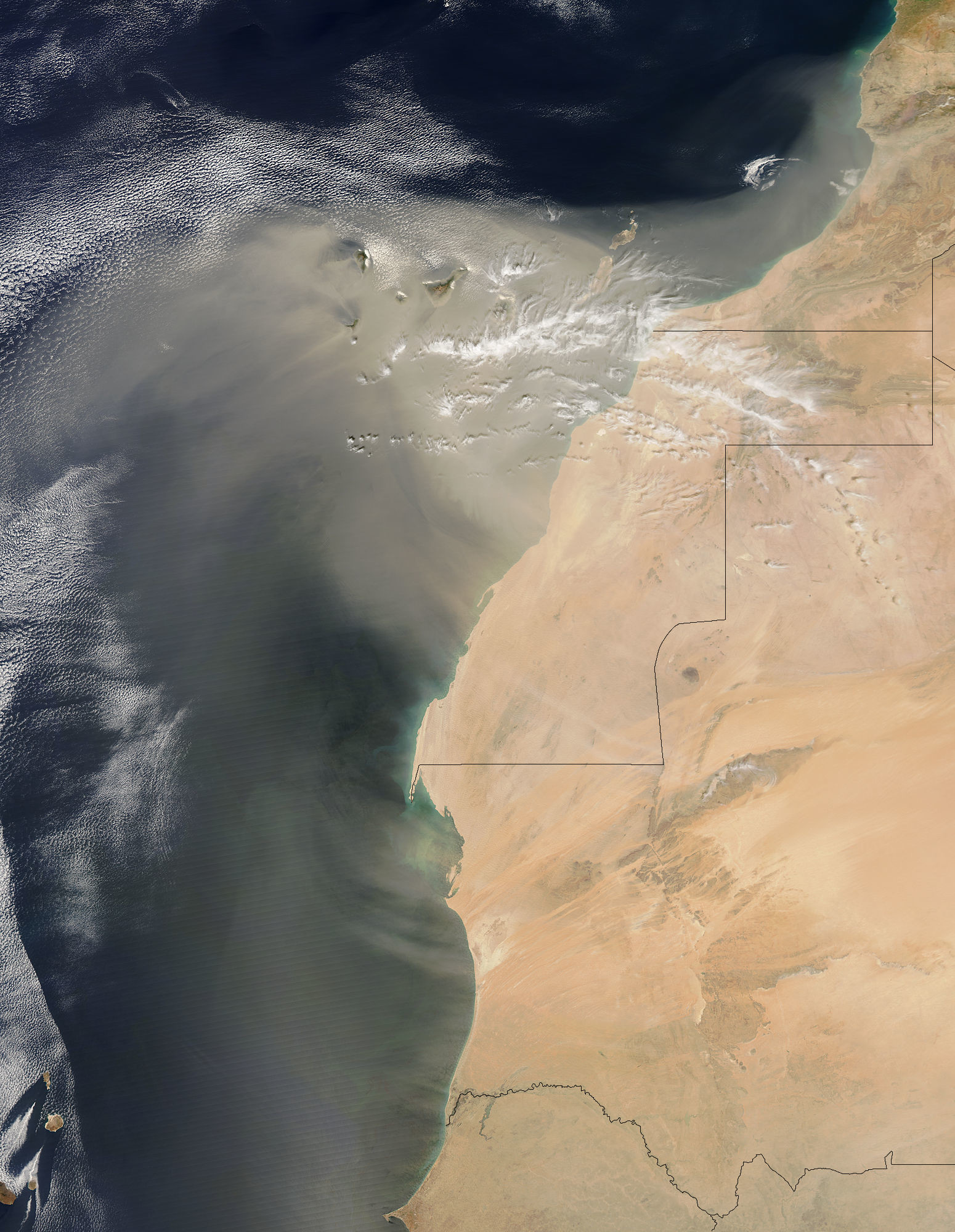

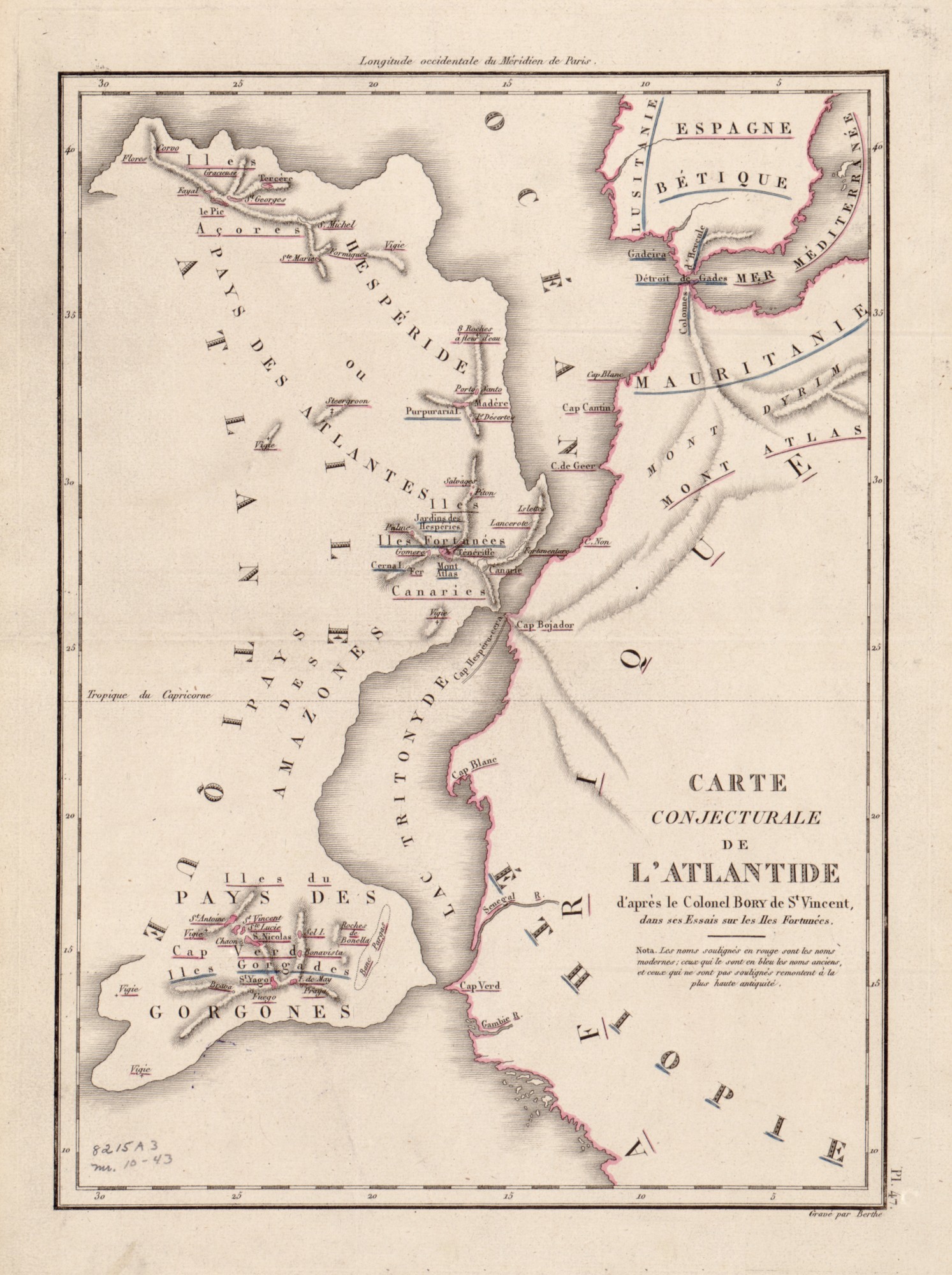

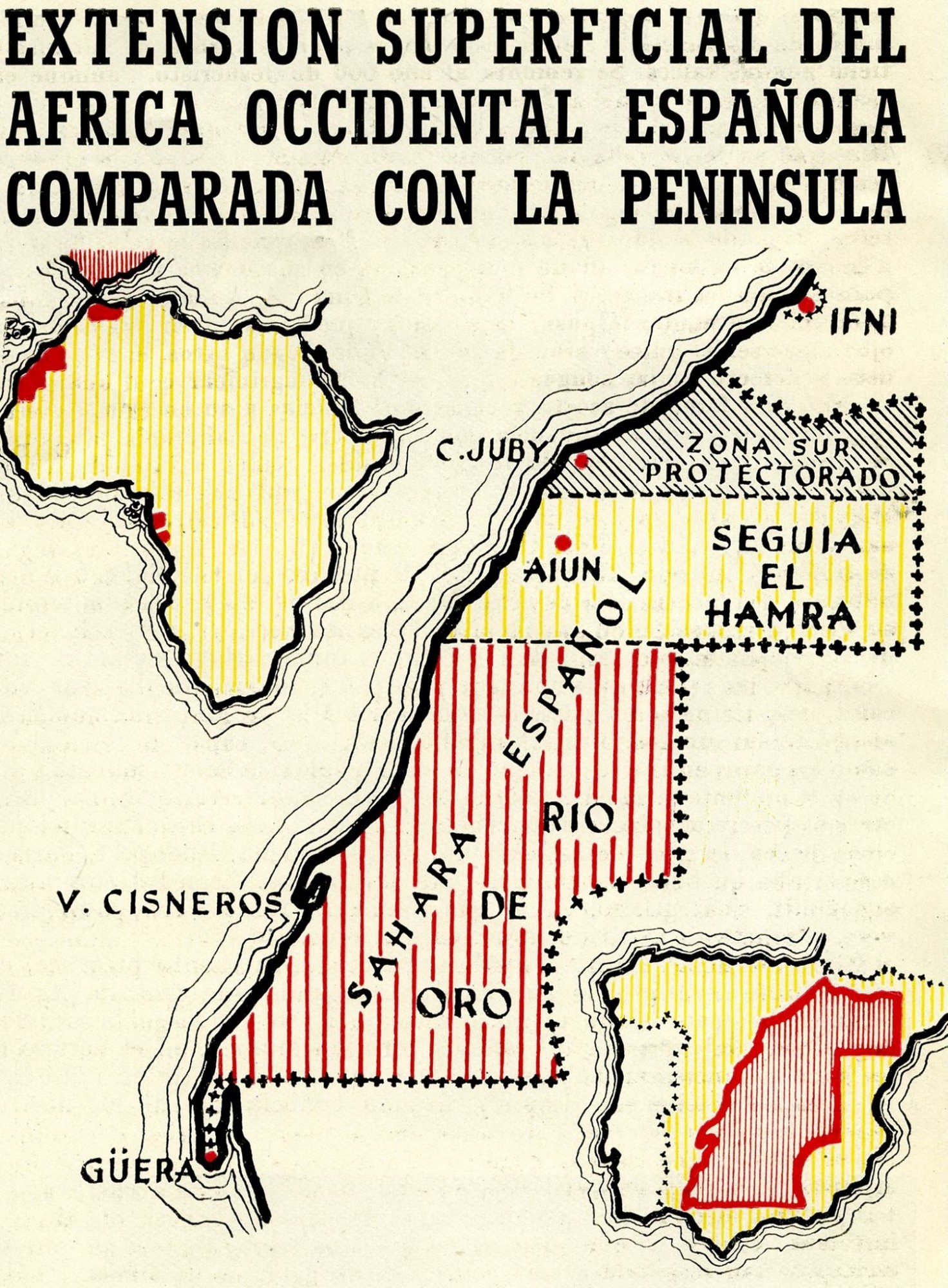

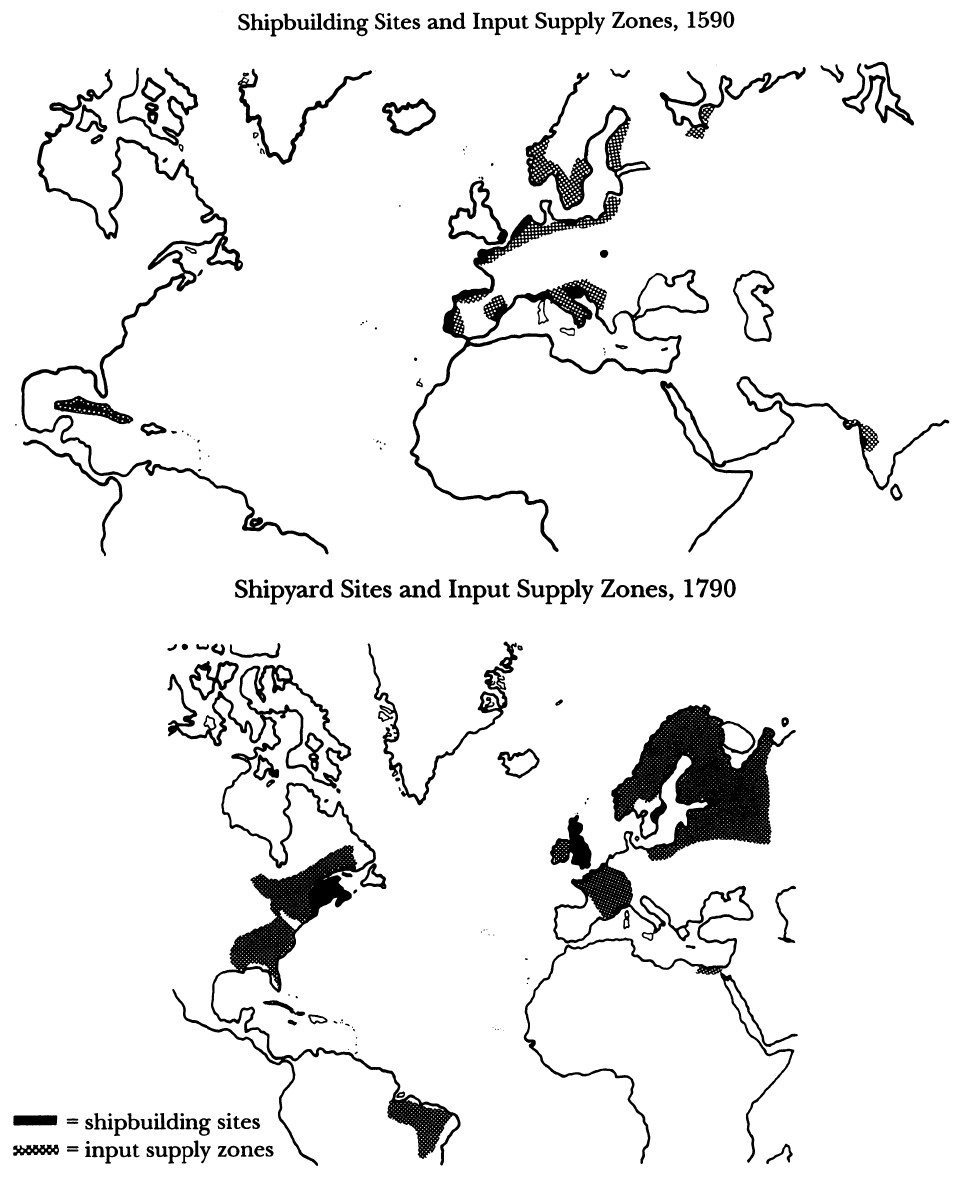

In 1479, the Treaty of Alcáçovas-Toledo formalized the Crown of Castille’s rights over Boujdour (in Western Sahara) up to Agadir (in Morocco). For decades, Portugal and Castille disputed over raid and fishing rights, or what Lino Camprubí has called “resource-based sovereignty,” which was temporarily resolved by the Treaty of Tordesillas in 1494, separating territory and water rights between the two crowns. Later, in 1860, Morocco’s defeat to Spain, decreed in the Ouad Ras treaty between the kingdoms, granted the victor the right to establish a fishery off the coast of a previous settlement in Santa Cruz de la Mar Pequeña (now Sidi Ifni in Western Sahara). In 1884, at the Berlin Conference, Spain’s claim over Western Sahara was granted, primarily due to its fishing potential. Thus, the right to fish in waters neighboring present-day Morocco and Western Sahara has been a source of contention and desire among various European powers, notably Spain and Portugal, for several centuries.

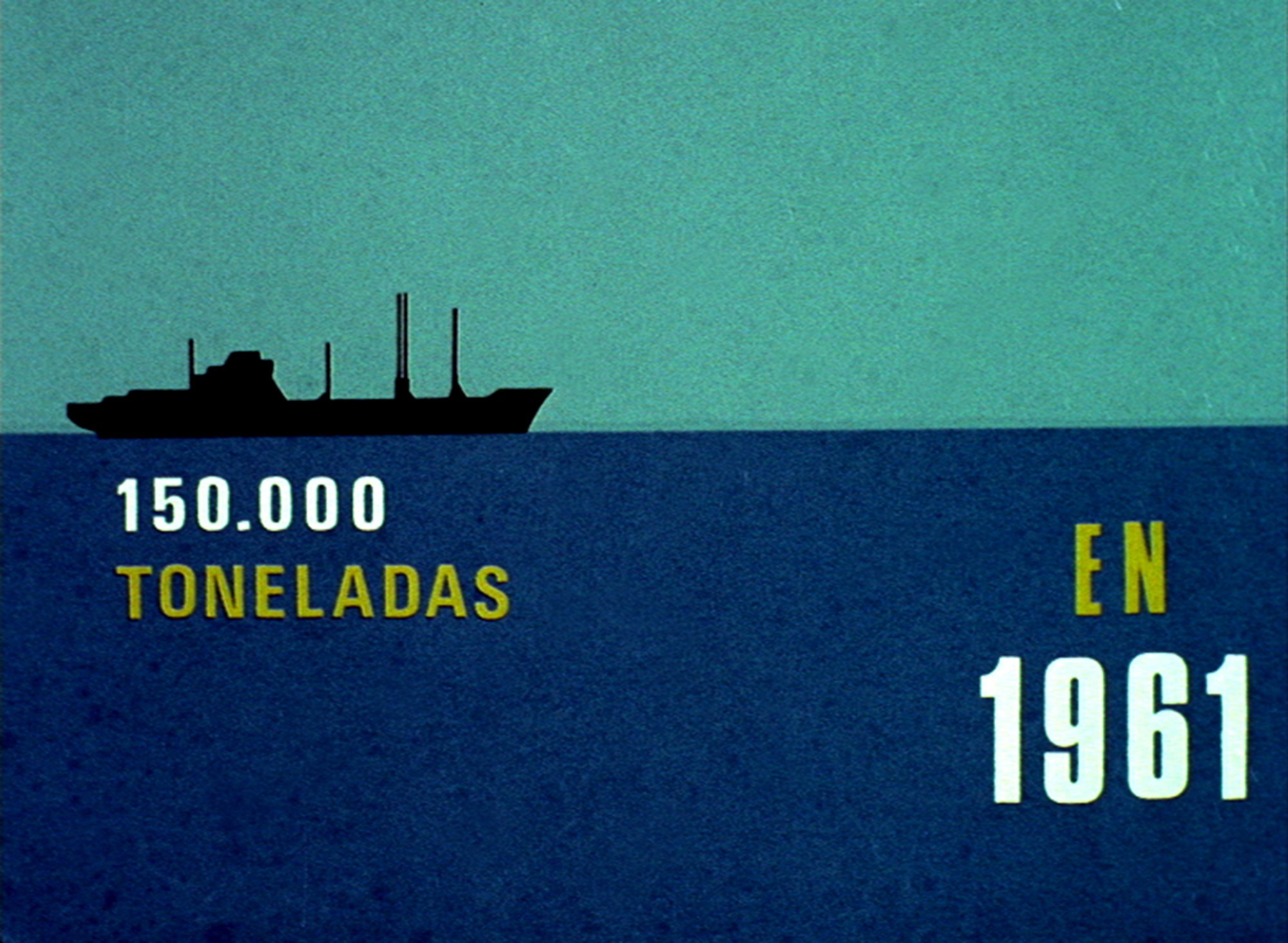

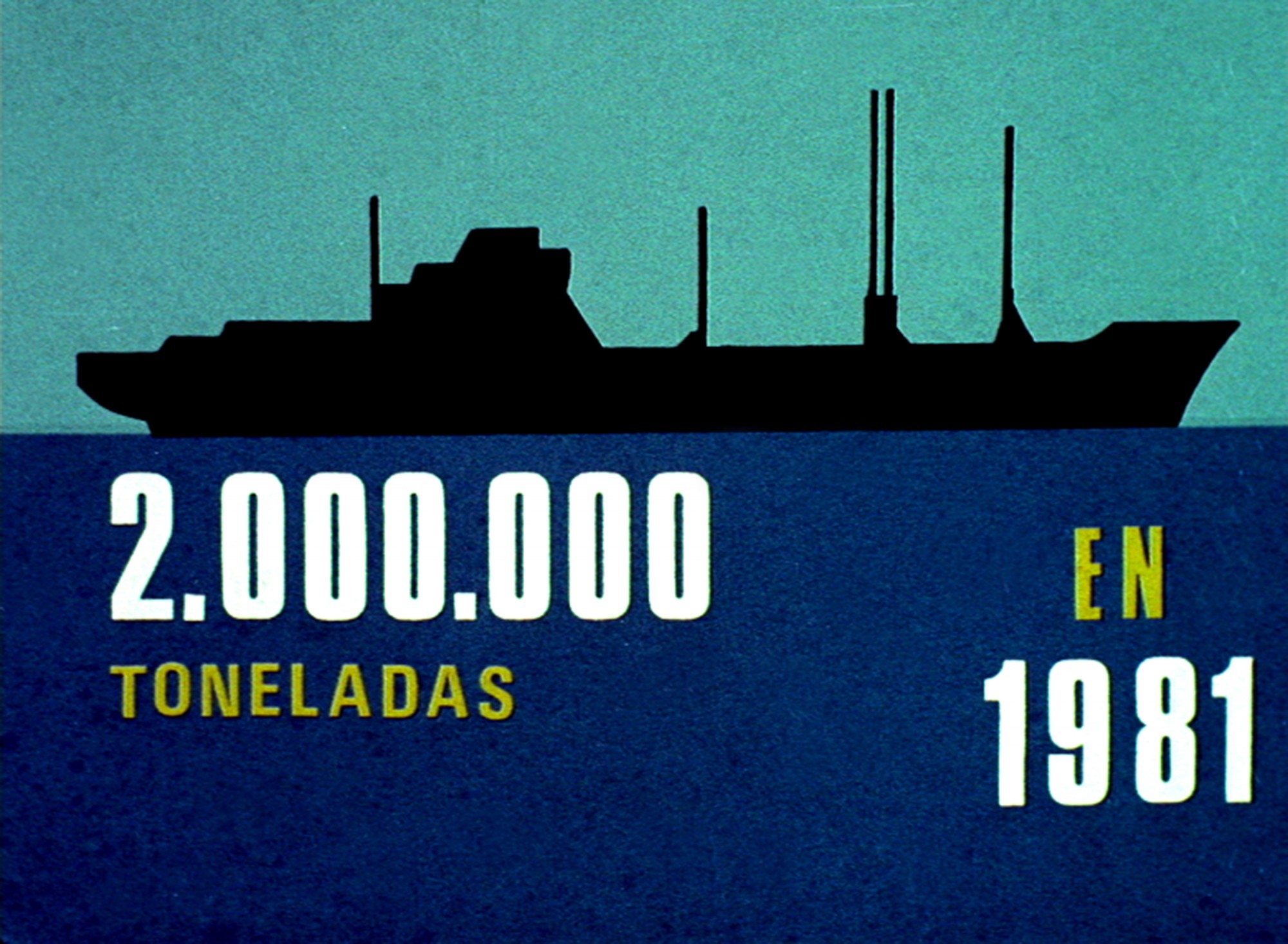

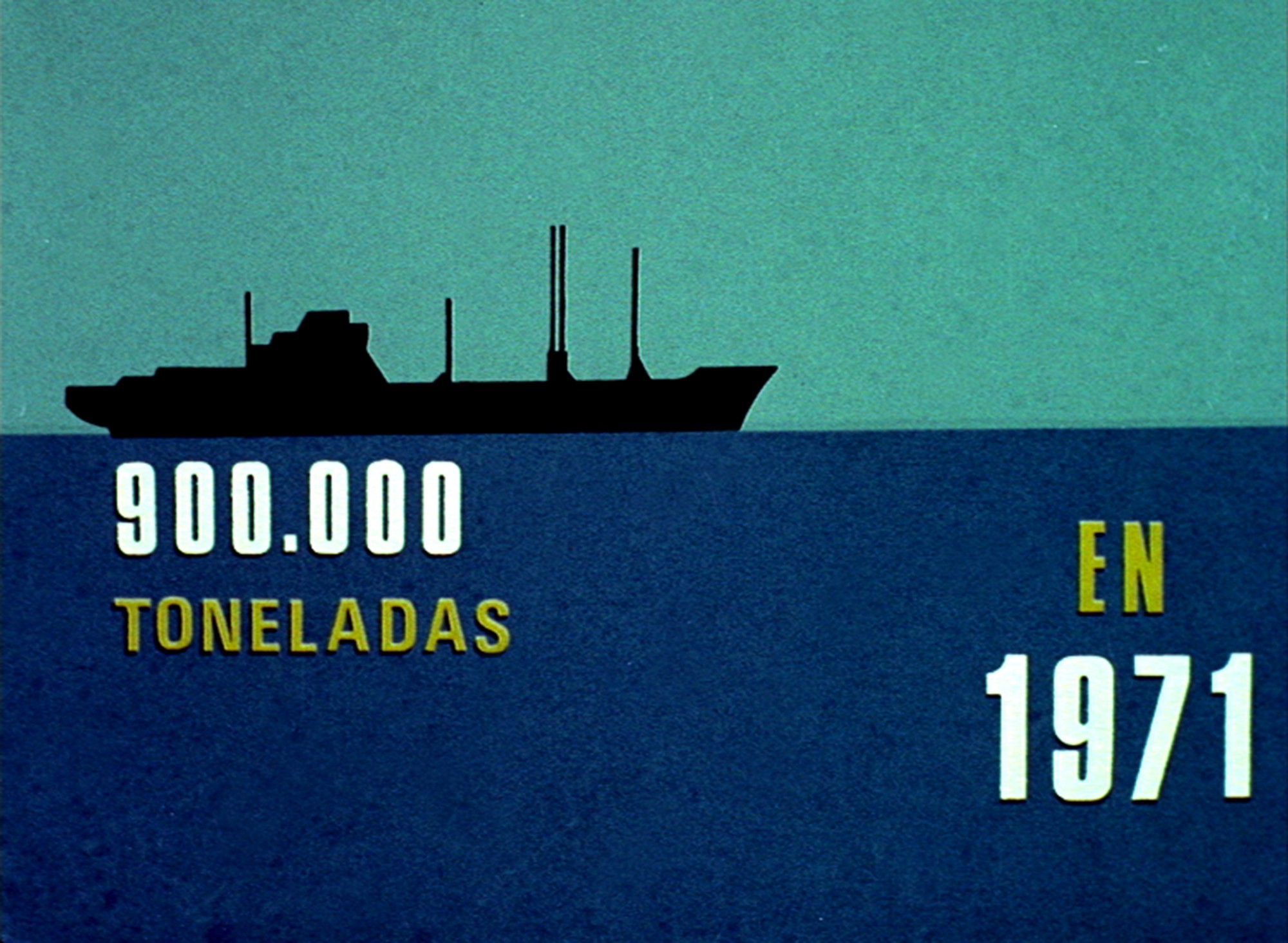

With the end of the civil war in Spain in 1939, marked by Franco’s victory, long-distance industrial fishing made a significant leap with the implementation of the Naval Credit Act. This act provided low-cost credit for fishing fleet construction and renewal with long-term repayment schemes. As a result, the fleet radically increased in size, leading to overfishing along the Spanish coasts. In this context, extraterritorial fishing was presented as a solution to overexploited peninsular waters and begins to explain how Spain became the largest fleet in Europe.

…

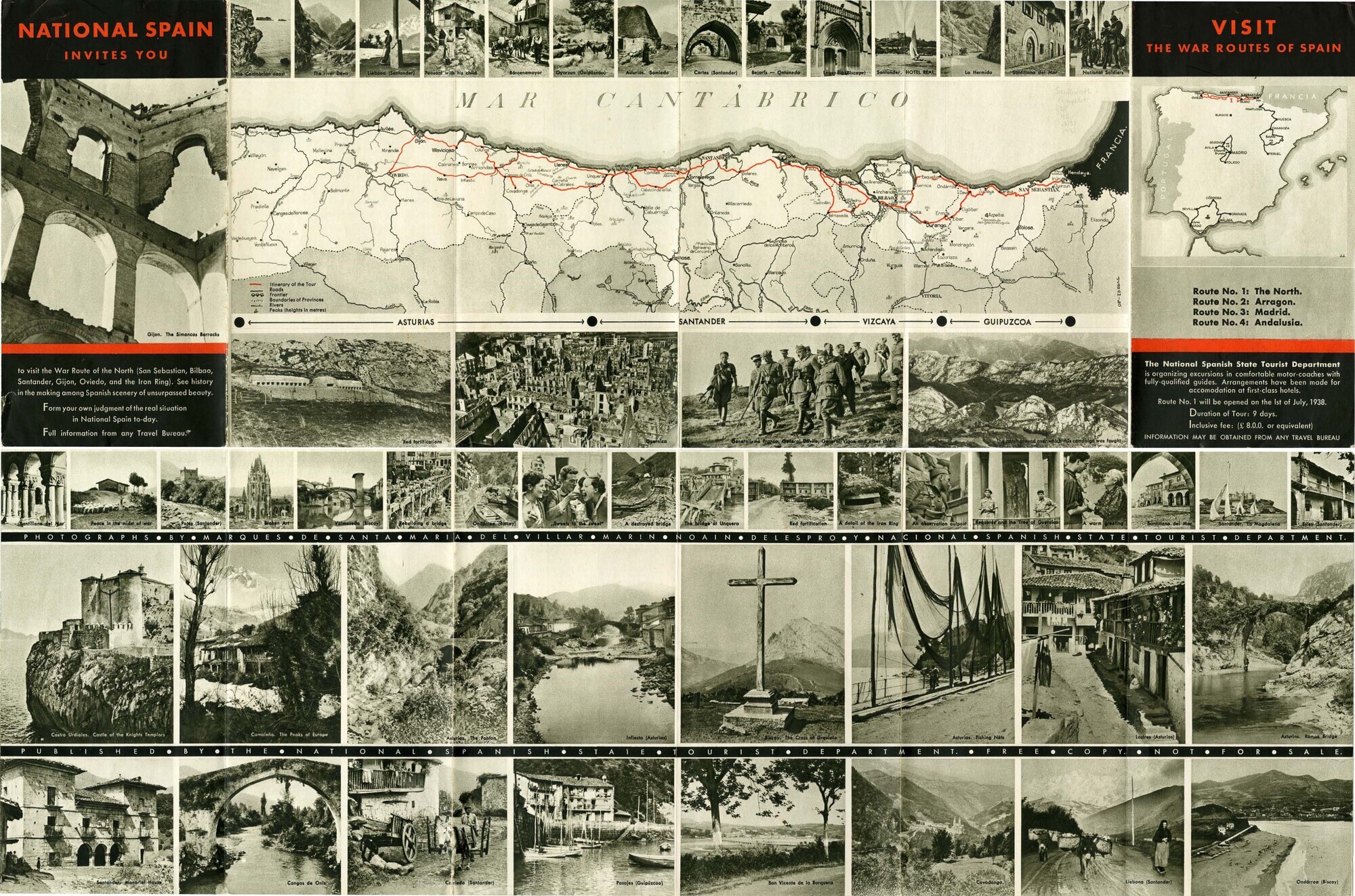

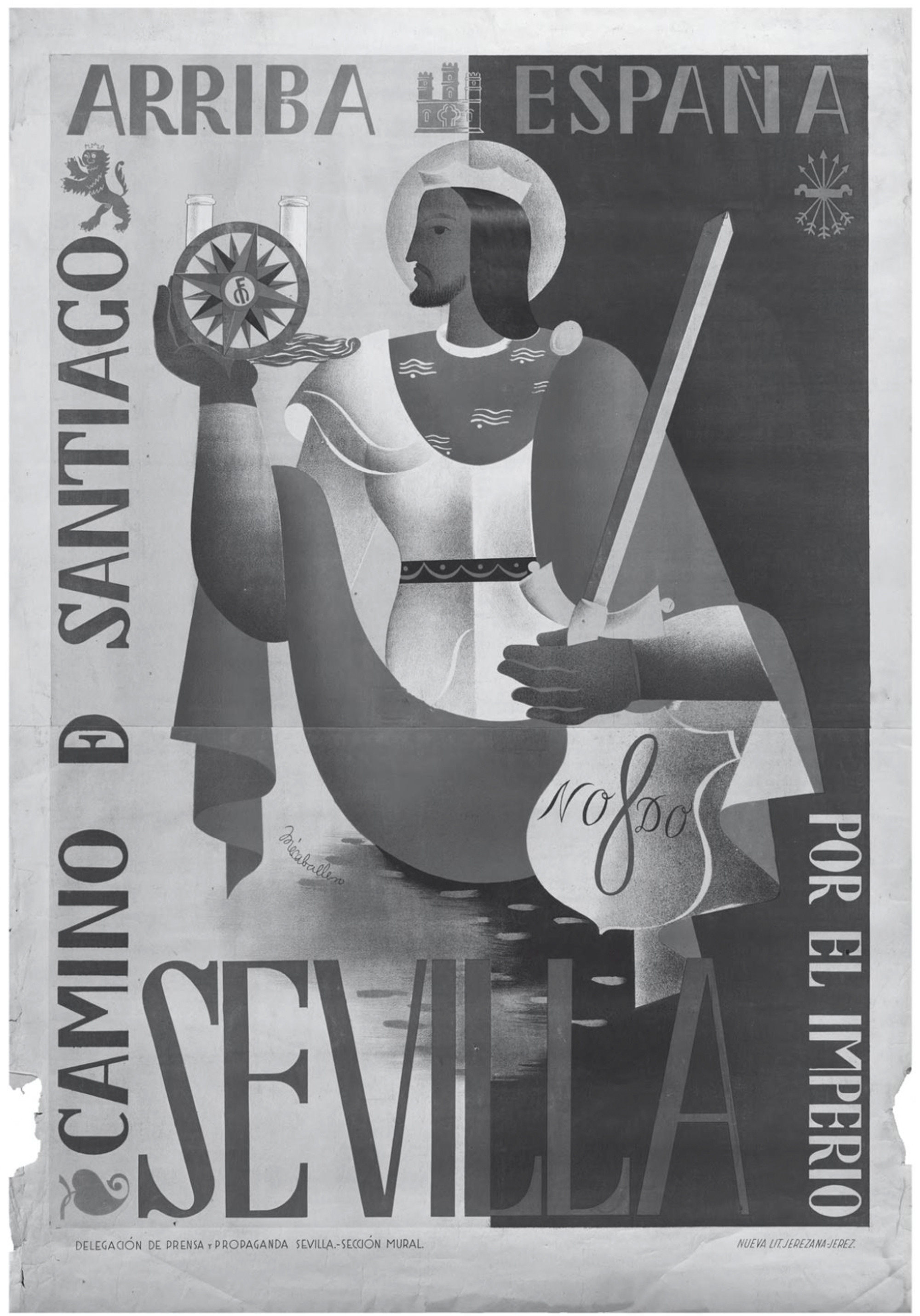

NO-DO

NO-DO

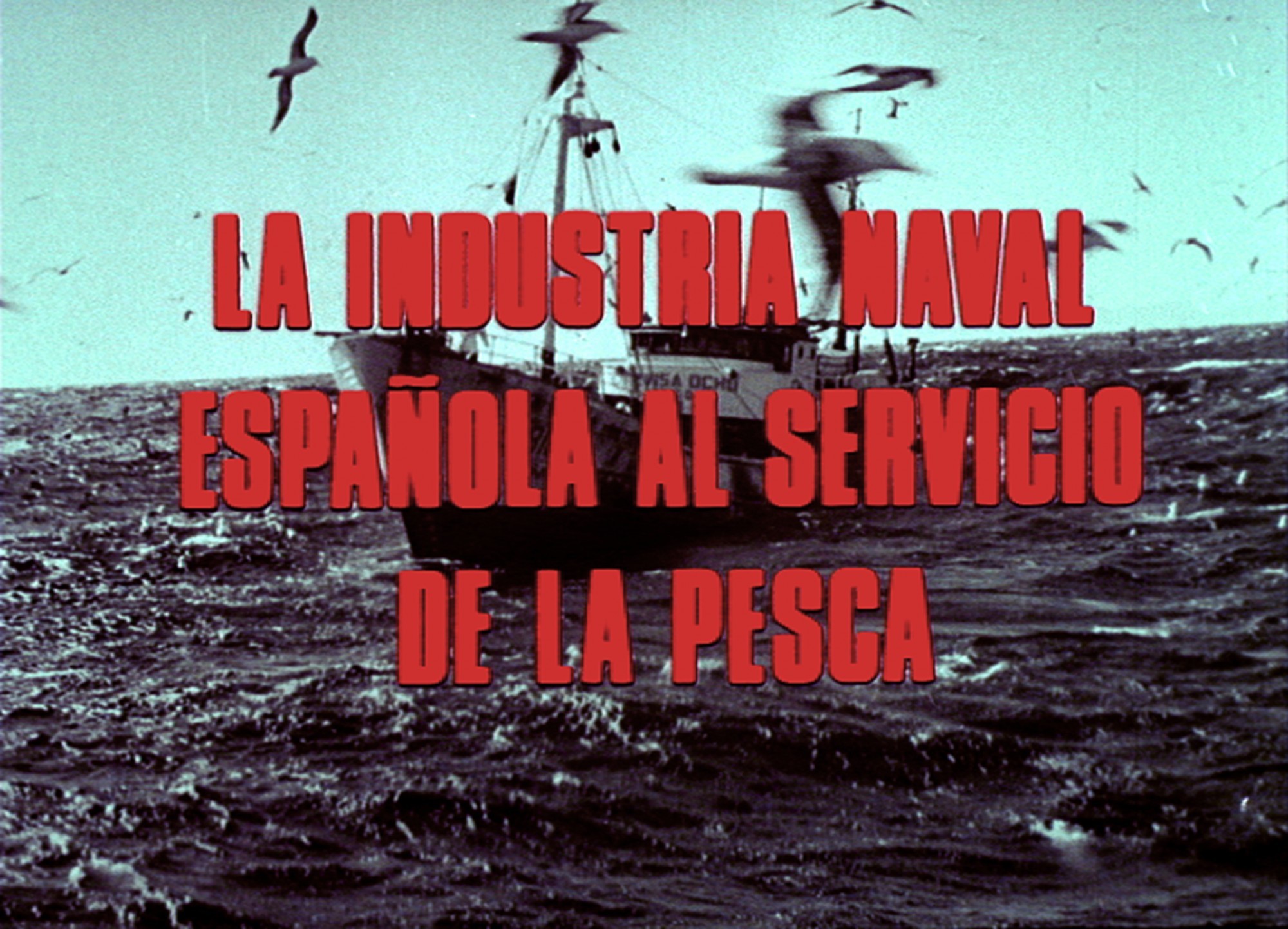

These NO-DOs, portraying the skilful fisherman Franco, functioned in juxtaposition with those documenting his presence at the inauguration of industrial fishing fleets, such as the Vimianzo, named after a city in Galicia. Other NO-DOs recounted Spain’s greatness as a fishing nation, namely showing the rail infrastructure that distributed the fish with such efficiency that it afforded the nicknaming of the landlocked capital Madrid: Puerto Pesquero (fishing port).

…

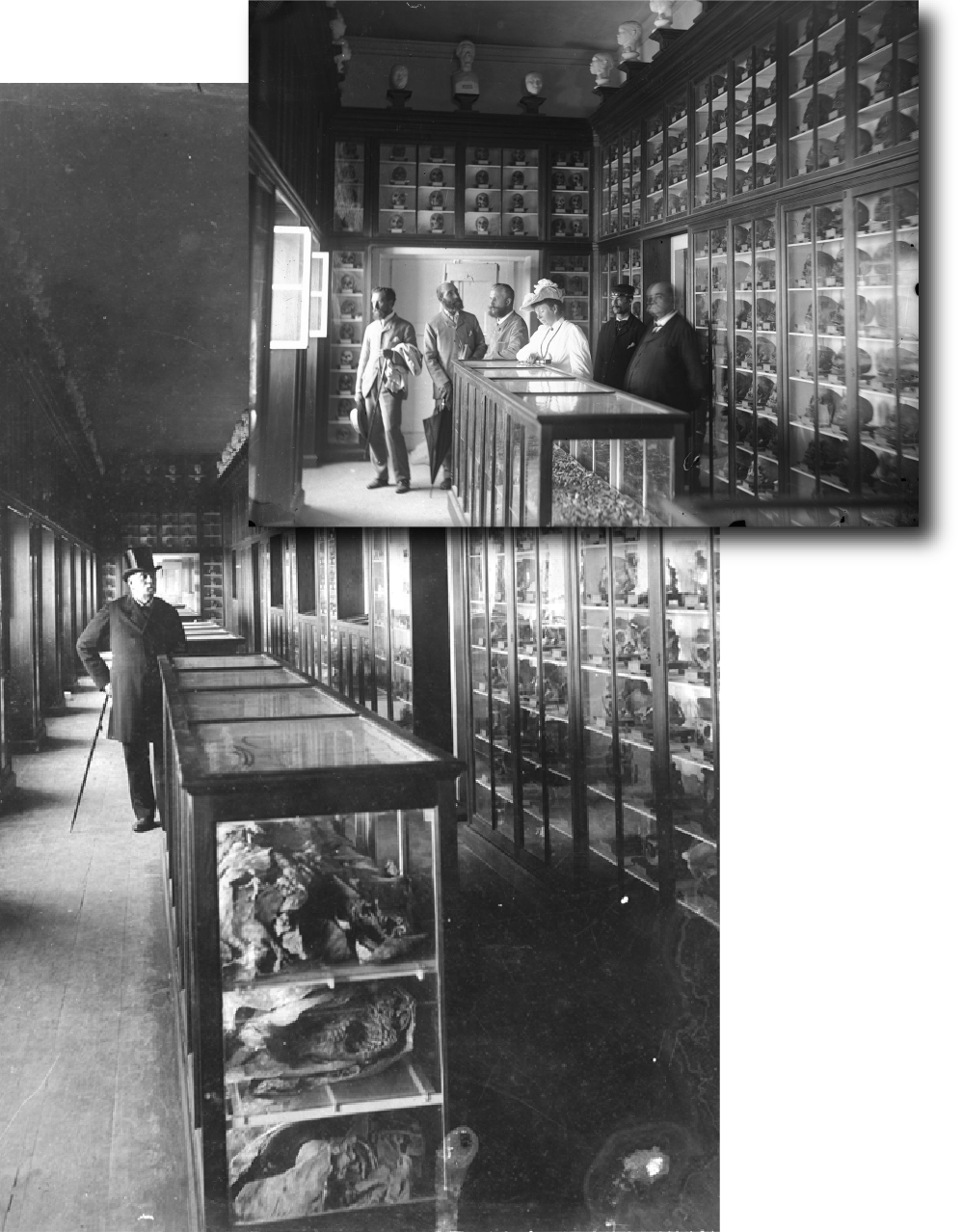

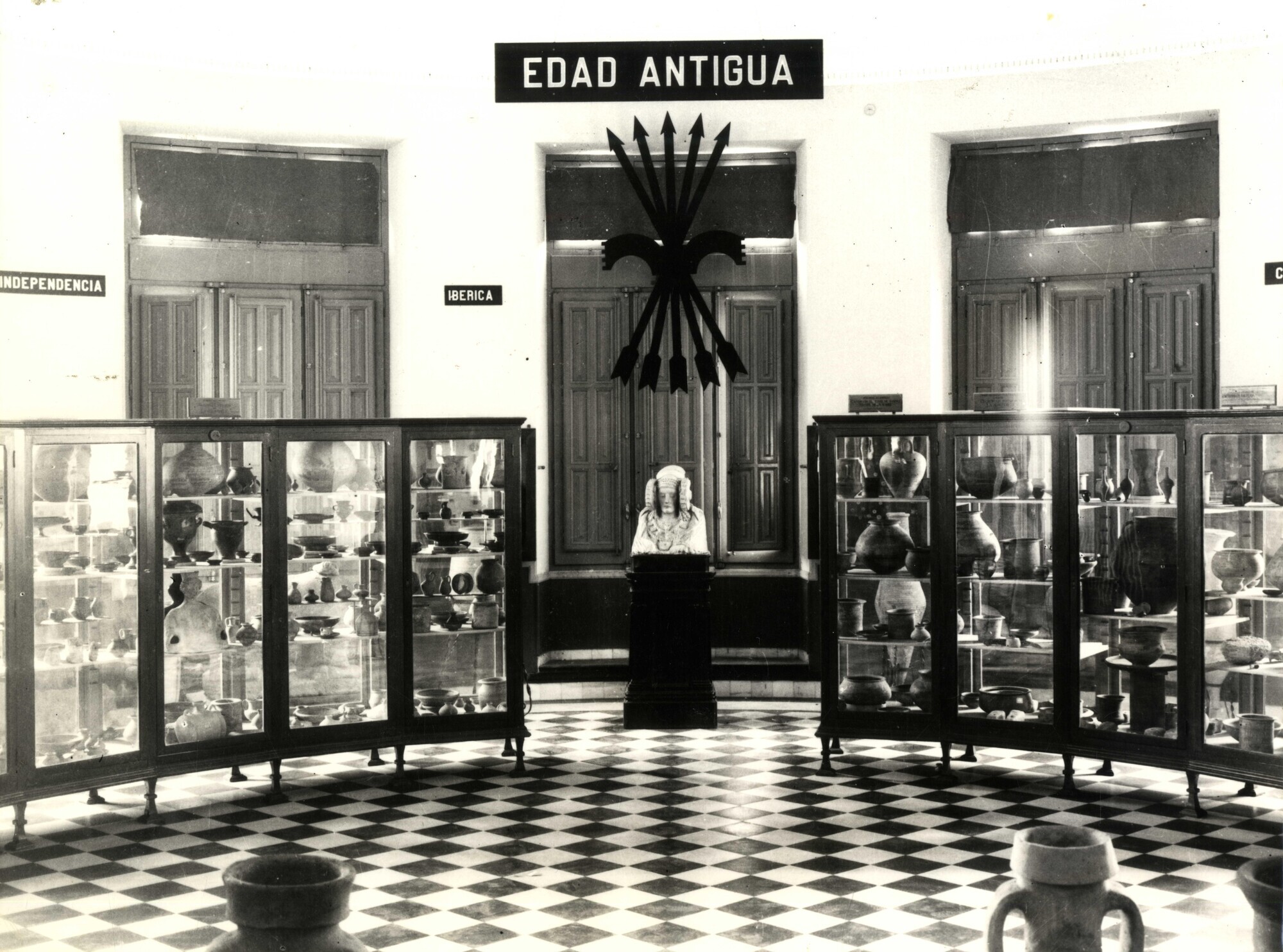

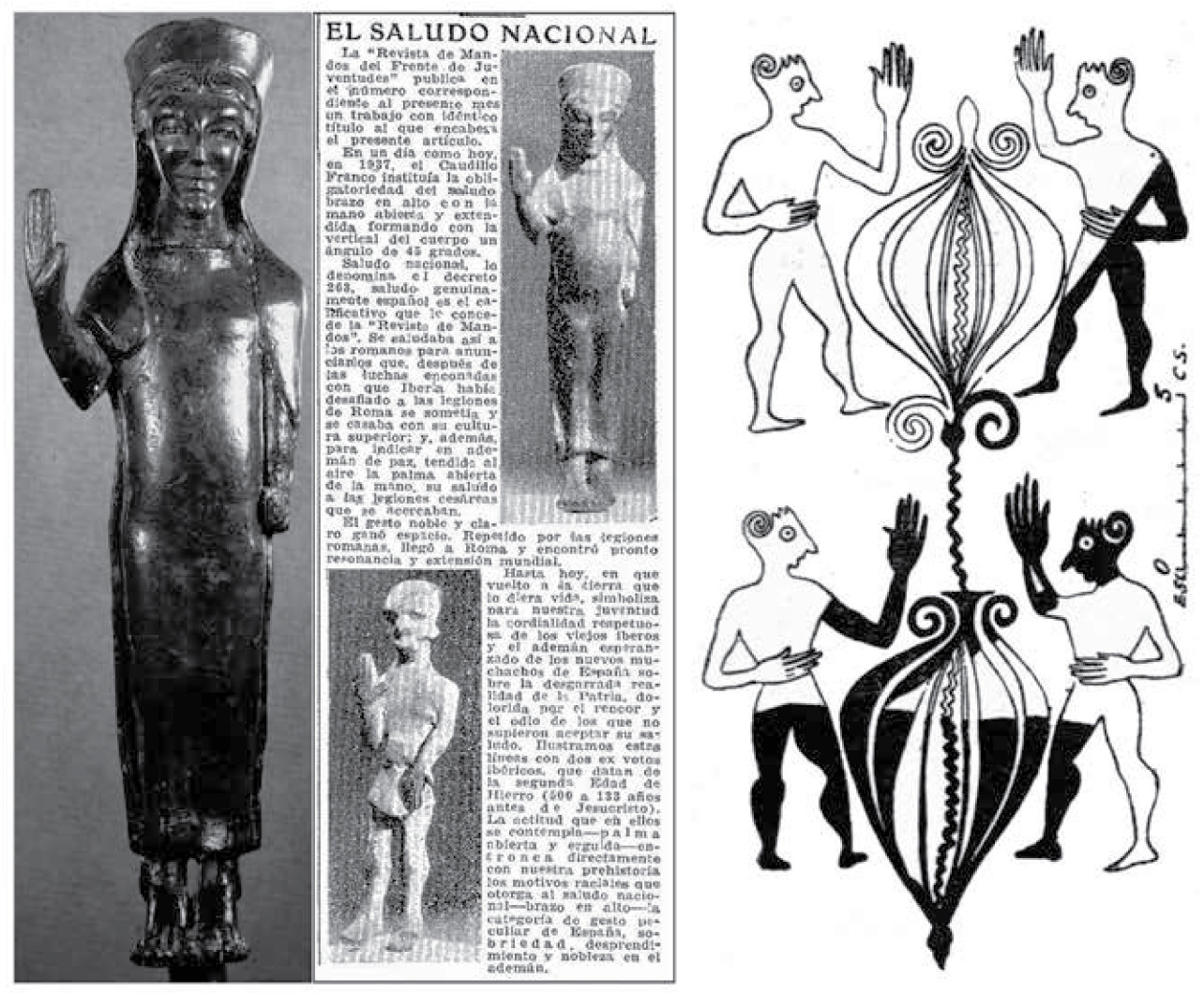

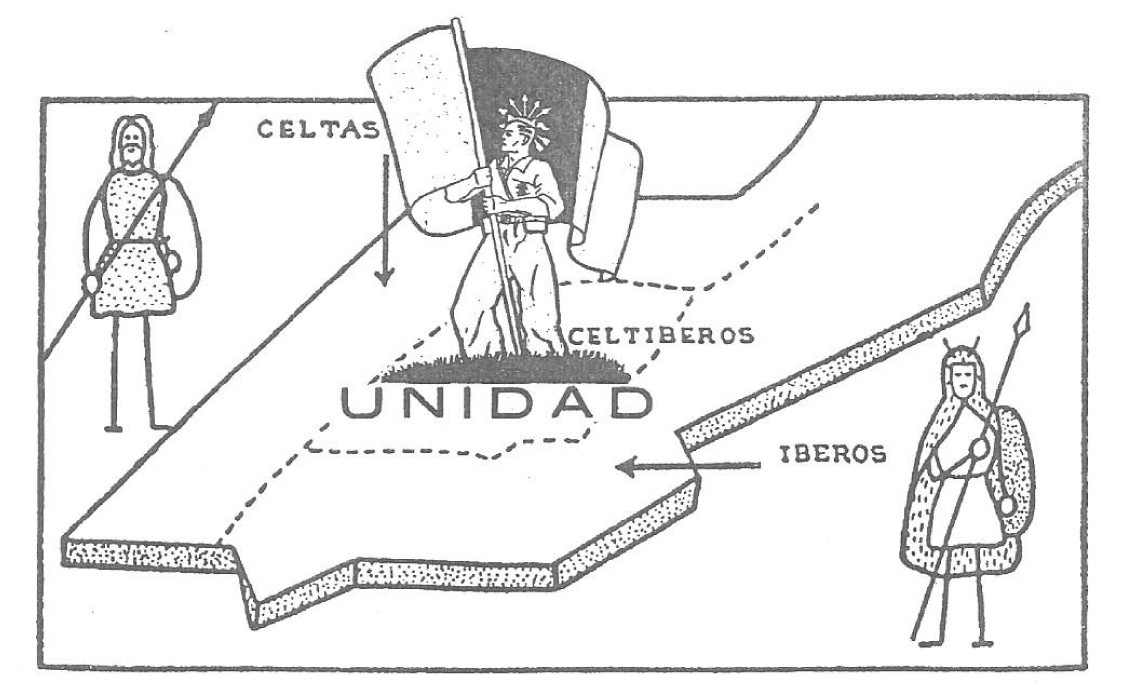

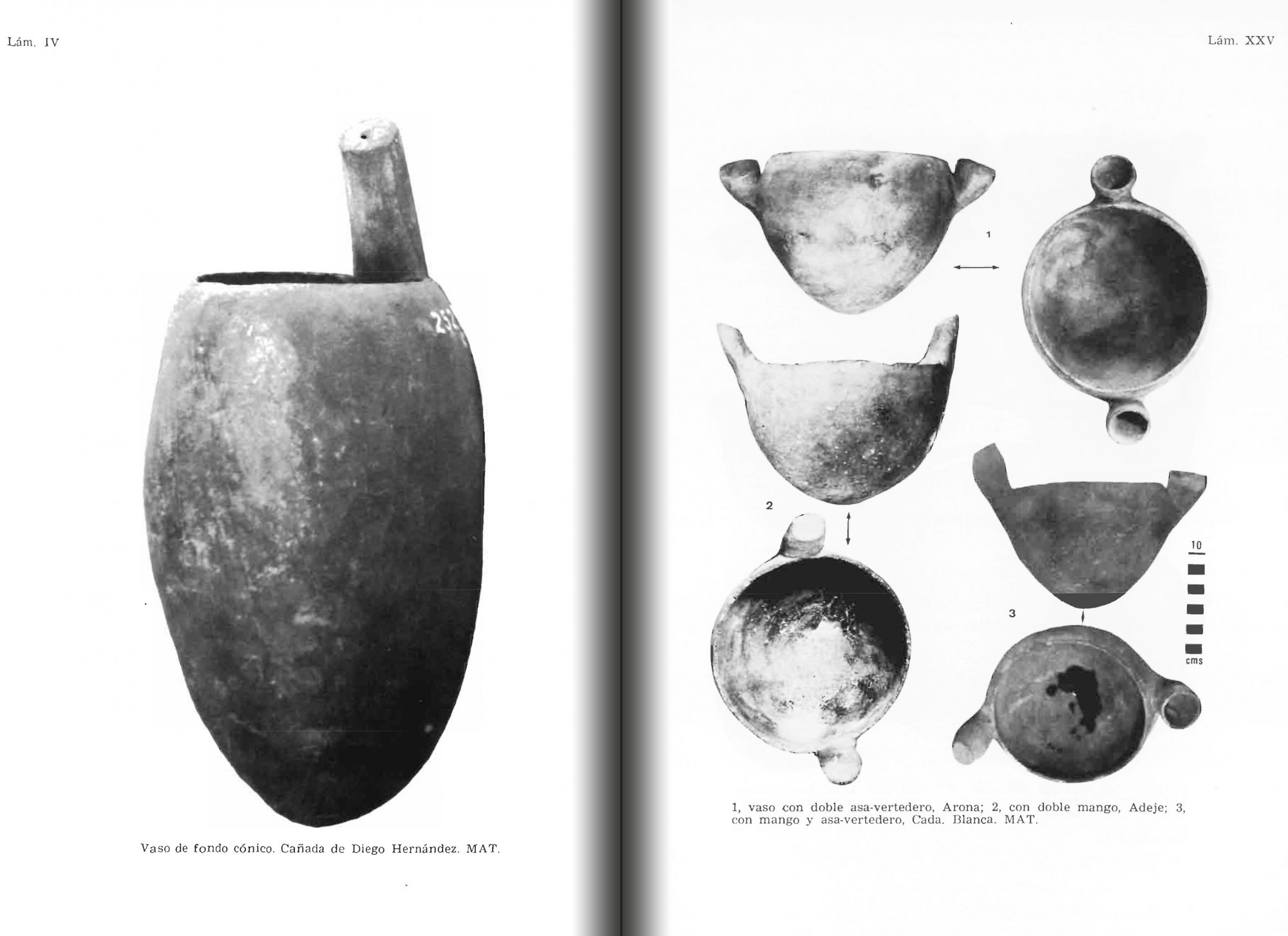

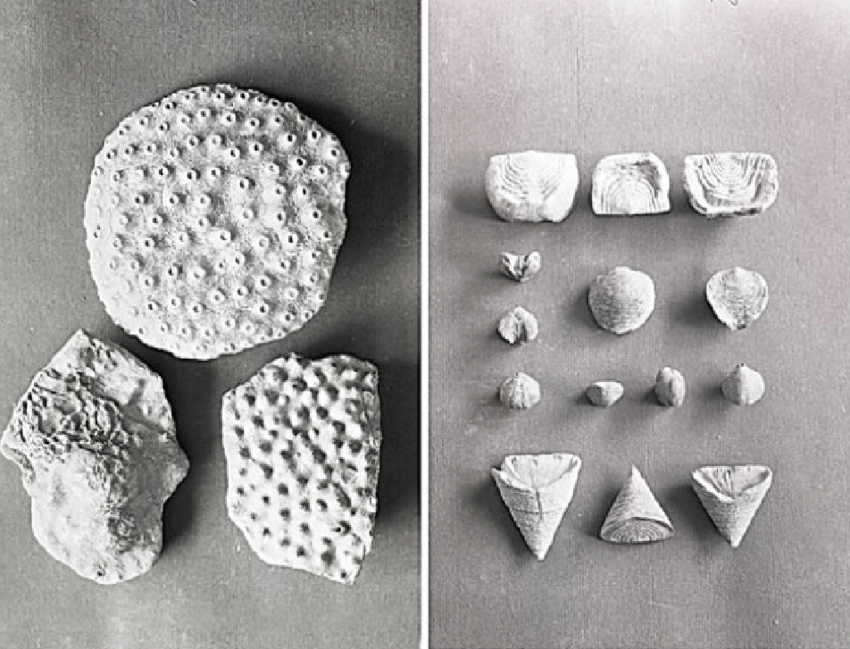

Francoist Archaeology

Francoist Archaeology

…

Jable Rubio

Jable Rubio

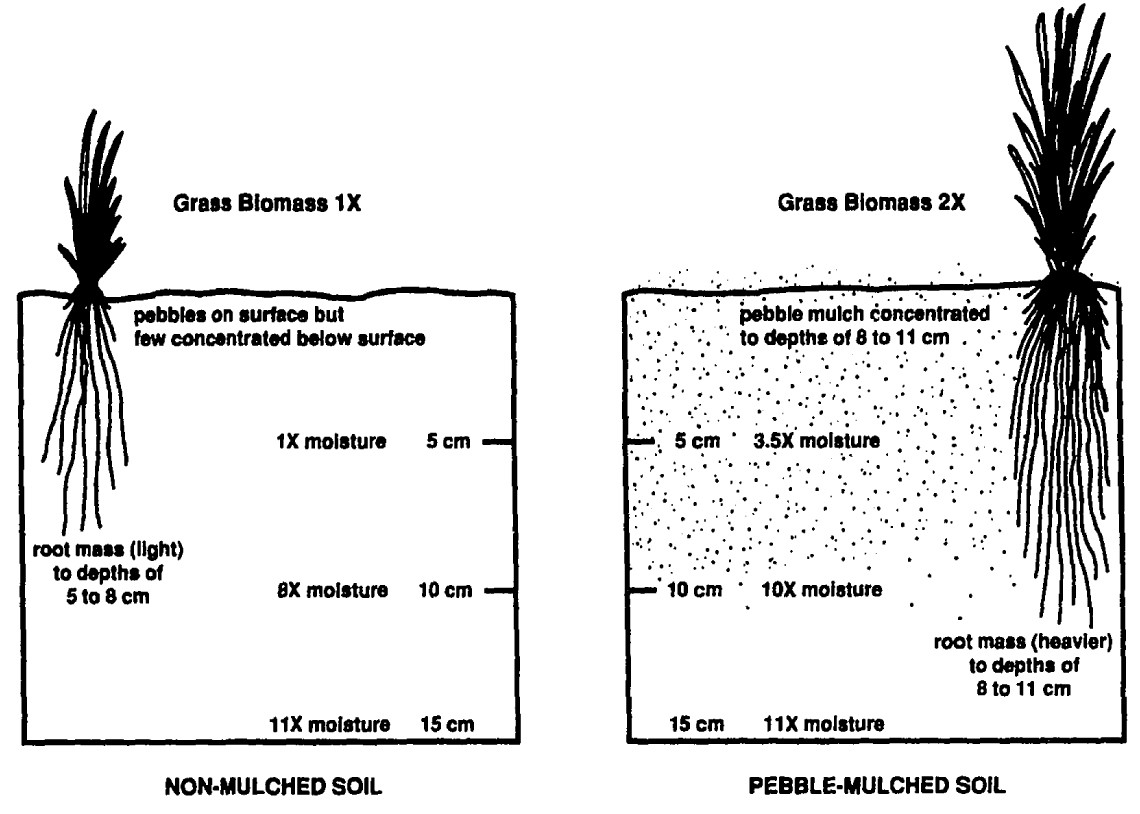

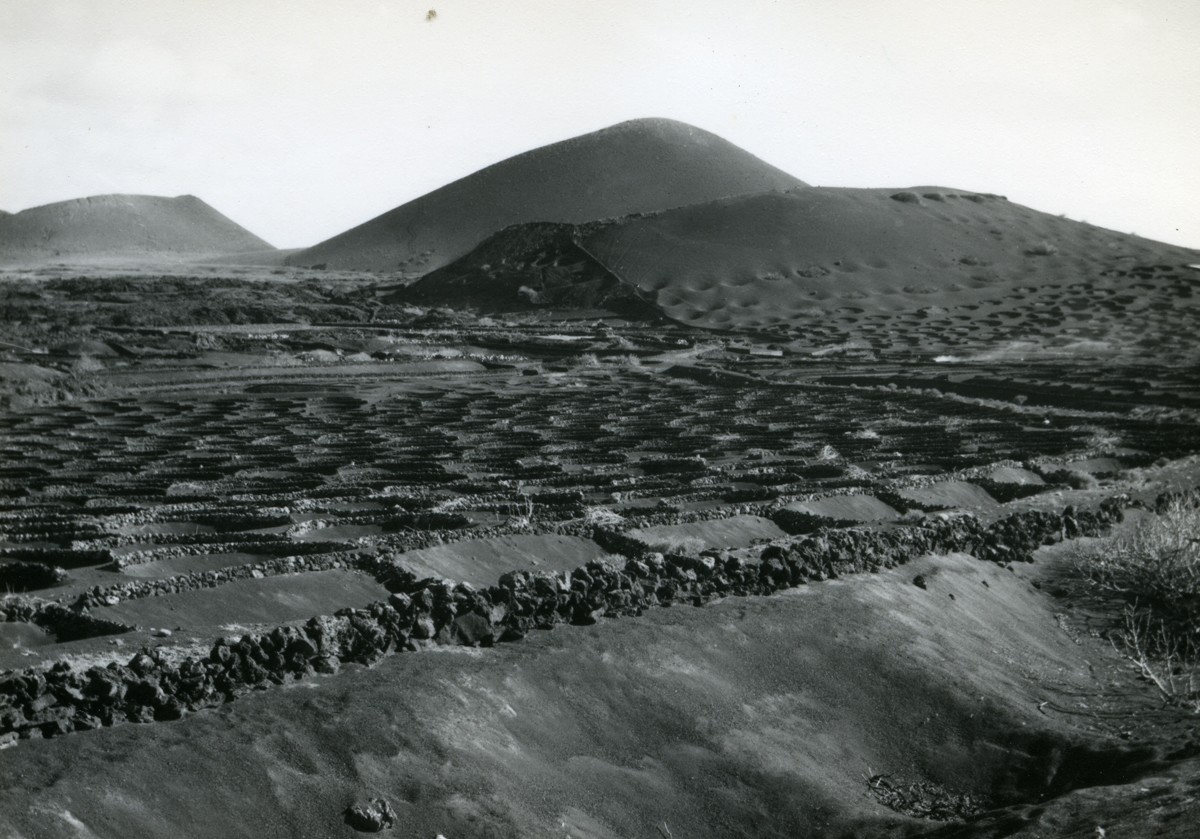

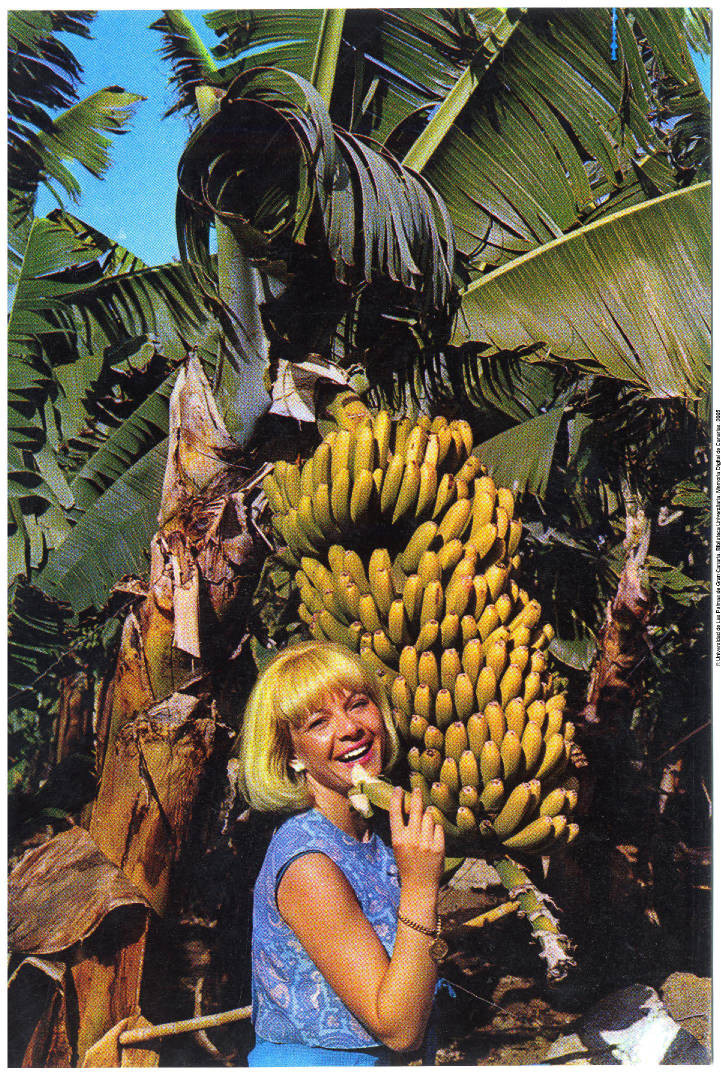

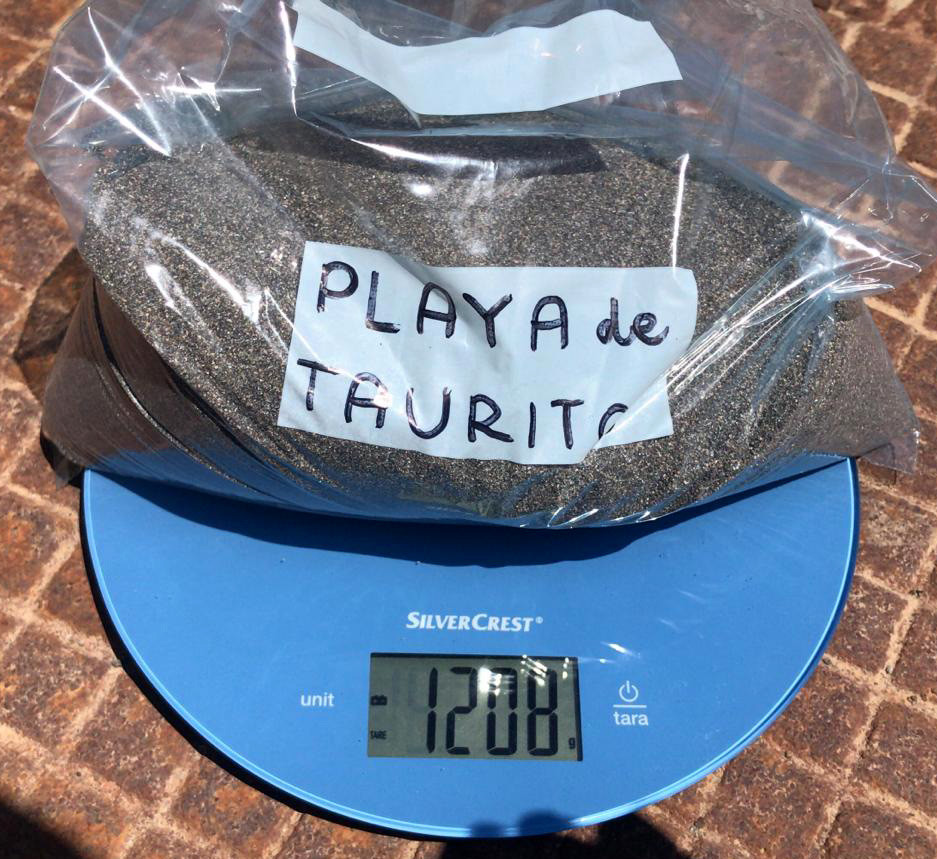

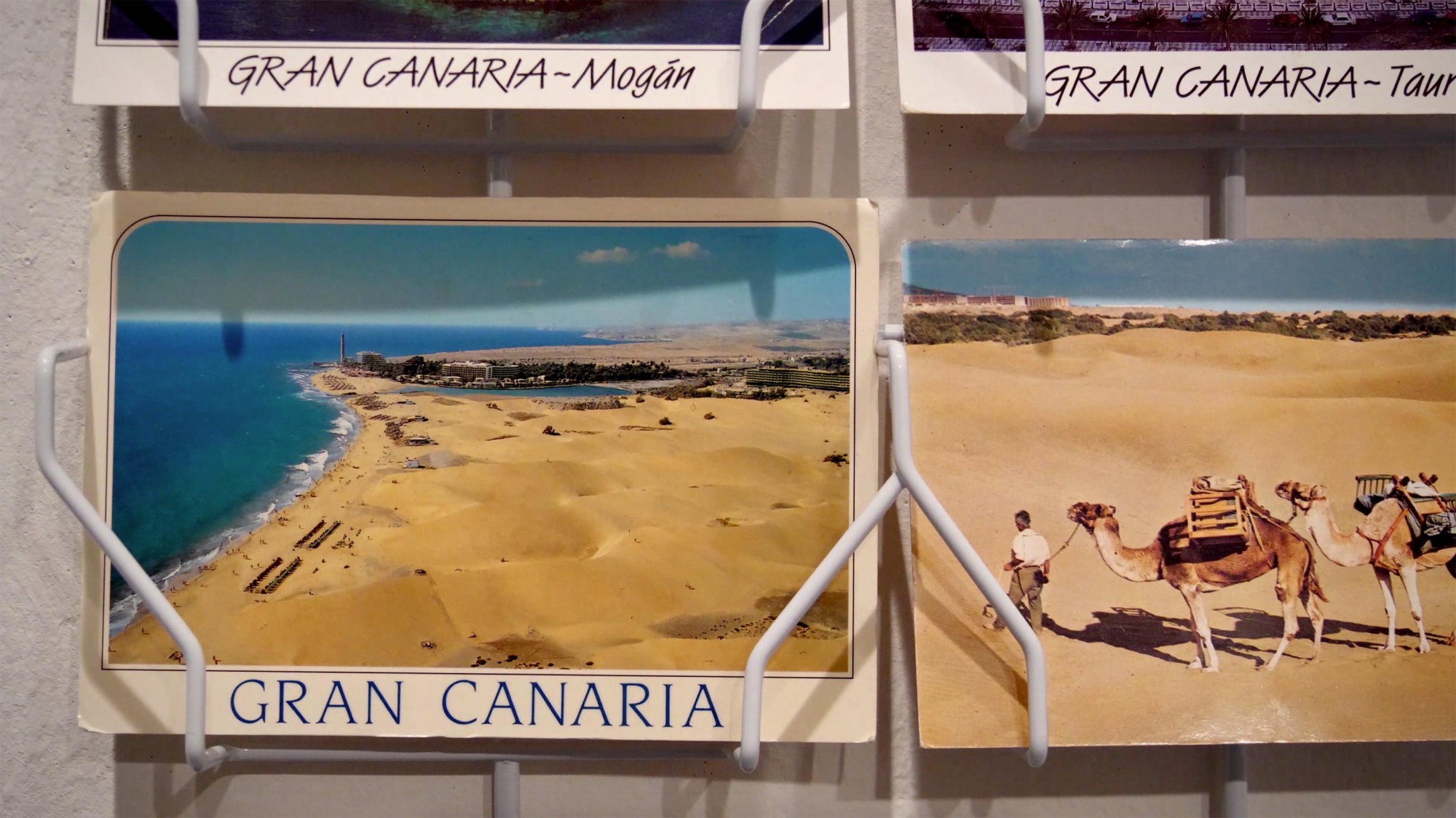

During the Francoist period, besides phosphate for fertilizer, or fishing grounds for an ever-expanding fishing fleet, large volumes of high-quality jable were imported from the Spanish Sahara colonies into the Islands of Tenerife or Las Palmas. Sand was initially employed for early truck-crop production of sand-bed tomato and banana plantations—a native farming technique from the desert island of Lanzarote which was later rolled over the export-oriented greenhouse region of El Ejido (Almeria). In a 1958 copy of the magazine Falange: Diario de la Tarde, a feat of Lanzarote local agriculture was worth noting in the caption of photo, disguising a 2 kg onion as a masterpiece of still life:

“No es un bodegón. El contenido de esta imagen pudiera parecer a primera vista la reproducción de una obra de arte pictórico. Pues no señor, no (sic) es, ni mas ni menos, que el voluminoso ejemplar de cebolla obtenido en tierra de secano de la isla de Lanzarote, que peso 2.04 kilogramos, y que actualmente se exhibe en una exposición de la capital tinerfeña.”

[It is not a still life. At first glance, the content of this image may appear to be an admirable work of fine art. Well, no sir no, it is no other than a voluminous specimen of onion, grown in unirrigated land in the island of Lanzarote, that weighs 2.04 kilograms, and currently being exhibited in an exhibition in the Tenerife.]

Later on, and at the midst of Spain’s fasticised modernity, white Saharan sand was mixed in concrete for the urban re-development of most islands of the archipelago. More importantly, this sand lined the beaches of Mogan or Tauro/Taurito in Las Palmas, or Las Teresitas in Tenerife. These geo-engineered seashore, in fact containing the world largest artificial beaches, transformed the rocky strands of traditional fishing and small holding communities into tourism heavens of eternal spring. on the African continent, but of European soil. Even now, beaches of most islands are regularly replenished with sand from the Western Sahara. The last sand shipment arrived to Mogan beach (Gran Canarias), on December 2019, as documented by Western Sahara Resource Watch (2019). The mining of Western Saharan sand started since the territory was incorporated as a Spanish Province—effectively a colony under the name of ‘Spanish Sahara’).

…

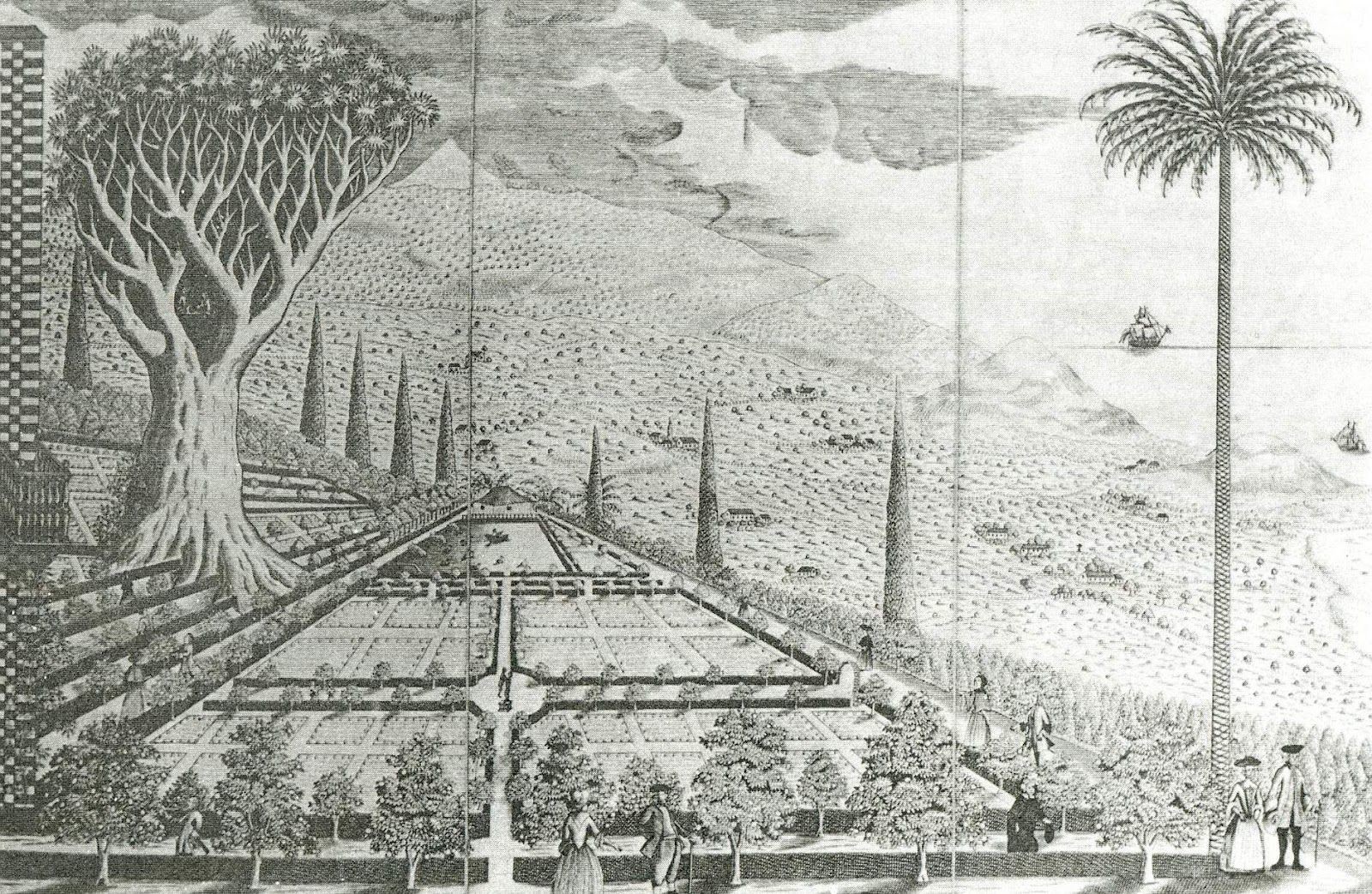

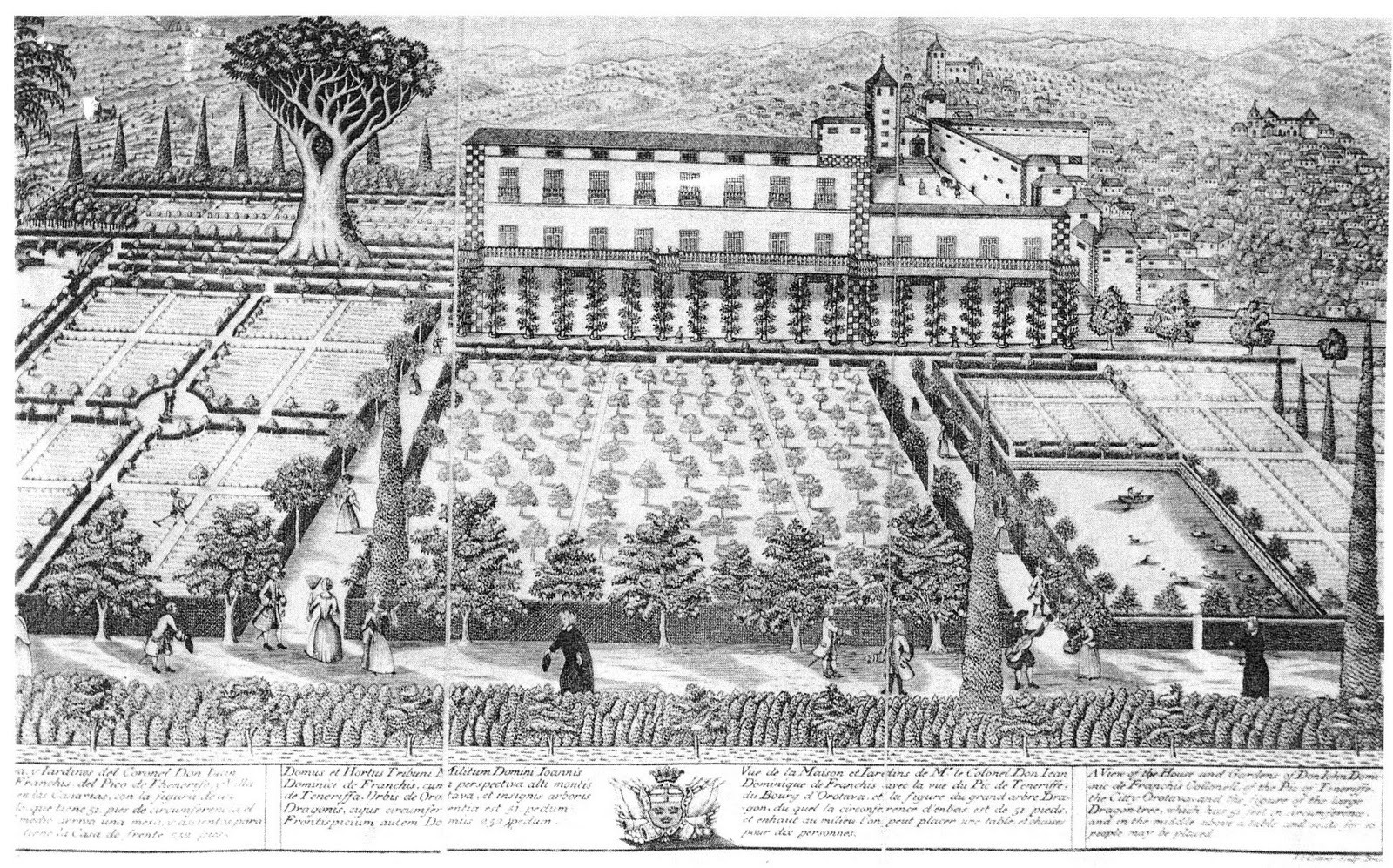

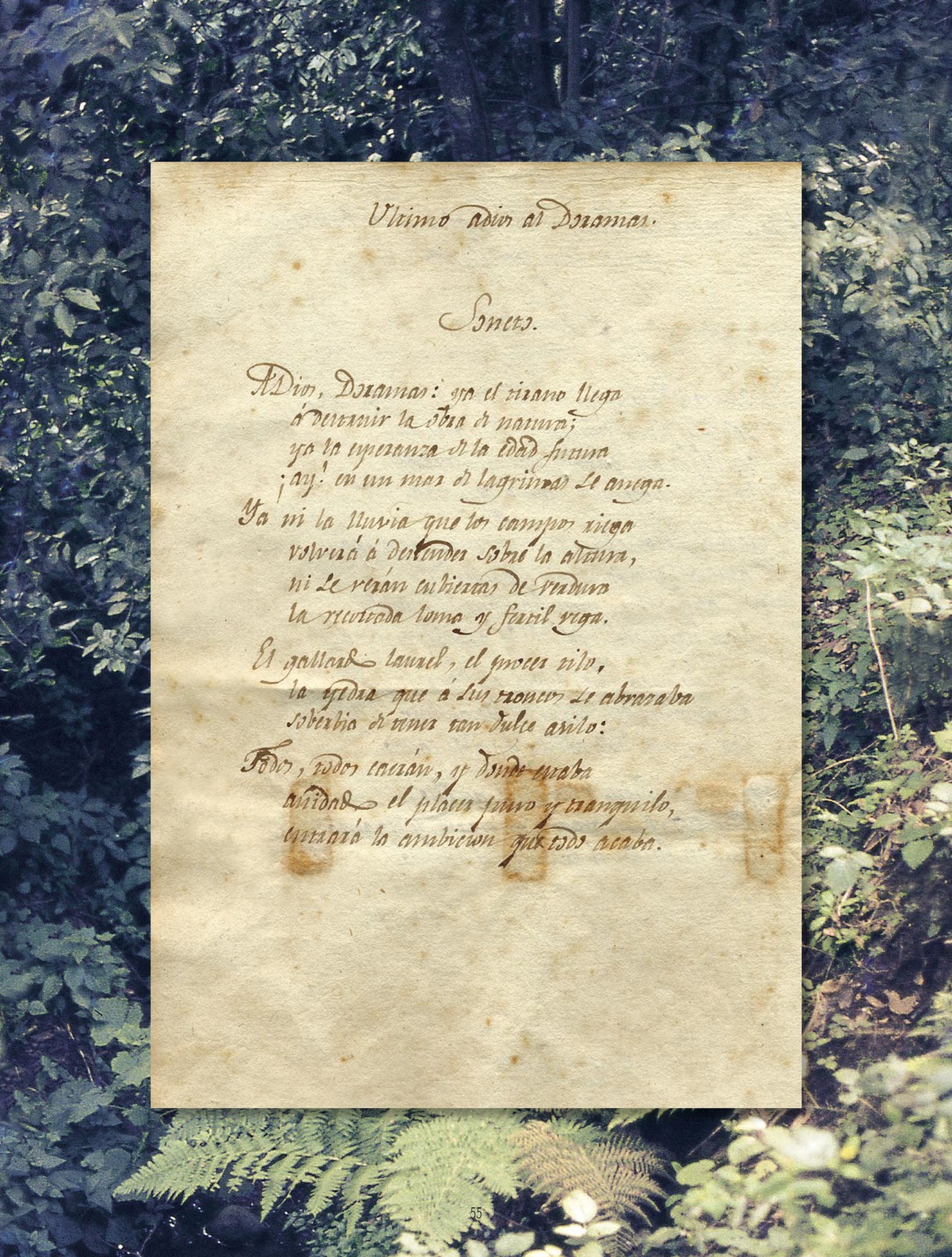

Garden of Hesperides

Garden of Hesperides

Adiós, Doramas: ya el tirano llega

a destruir la obra de Natura;

ya la esperanza de la edad futura

¡ay! en un mar de lágrimas se anega.

Ya ni la lluvia que los campos riega

volverá a descender sobre la altura,

ni se verán cubiertas de verdura

la recortada loma y fértil vega,

El gallardo laurel, el prócer tilo,

la yedra que a sus troncos se abrazaba

soberbia de tener tan dulce asilo:

Todos, todos caerán, y donde estaba

anidado el placer, puro y tranquilo,

entrará la ambición que todo acaba

Source: Rincones del Atlantico

…

Tourism and Information

Tourism and Information

…

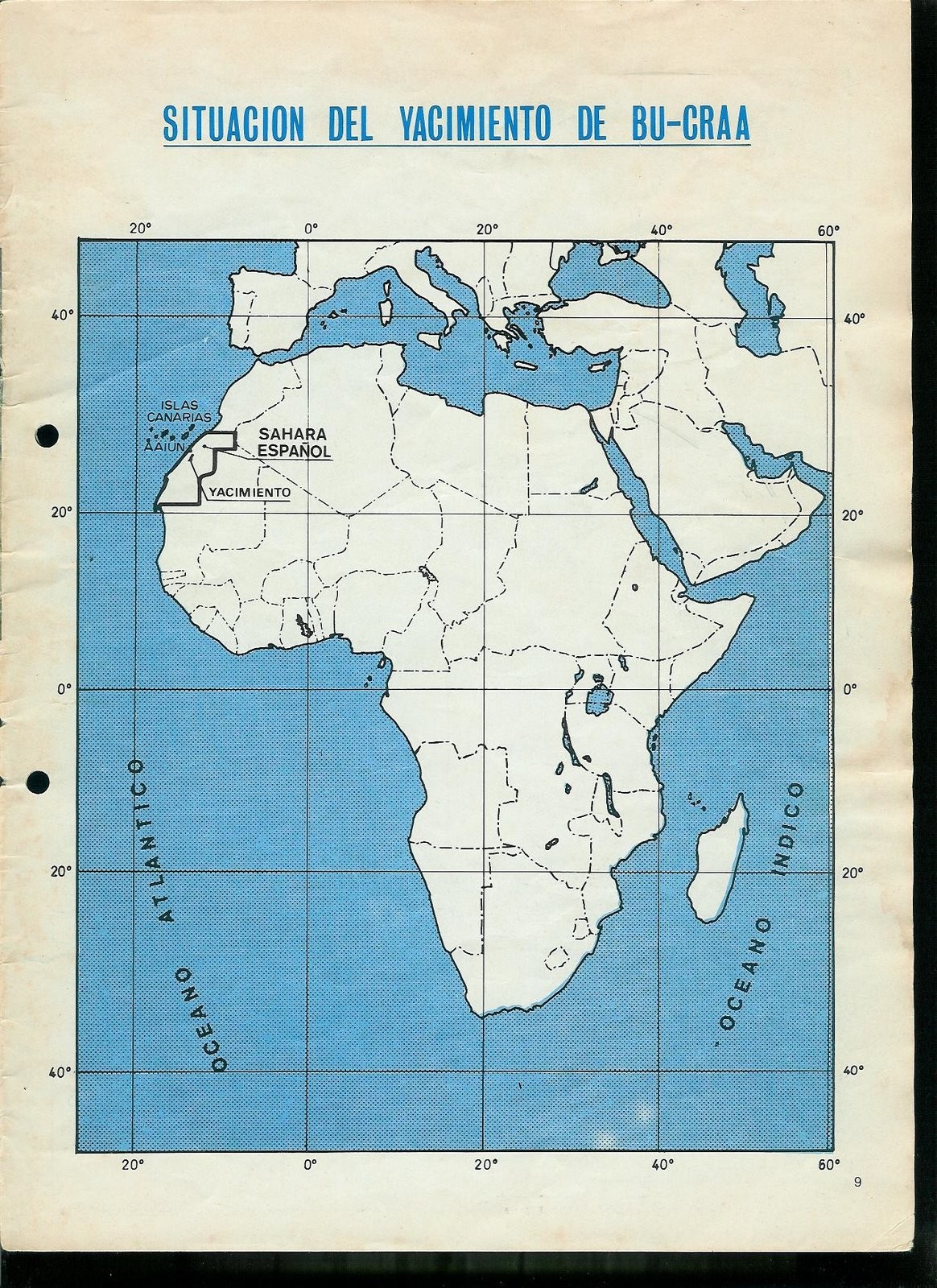

Bou Craa Mine

Bou Craa Mine

…

Phosphates

Phosphates

…

Infrastructural Colonialism

Infrastructural Colonialism

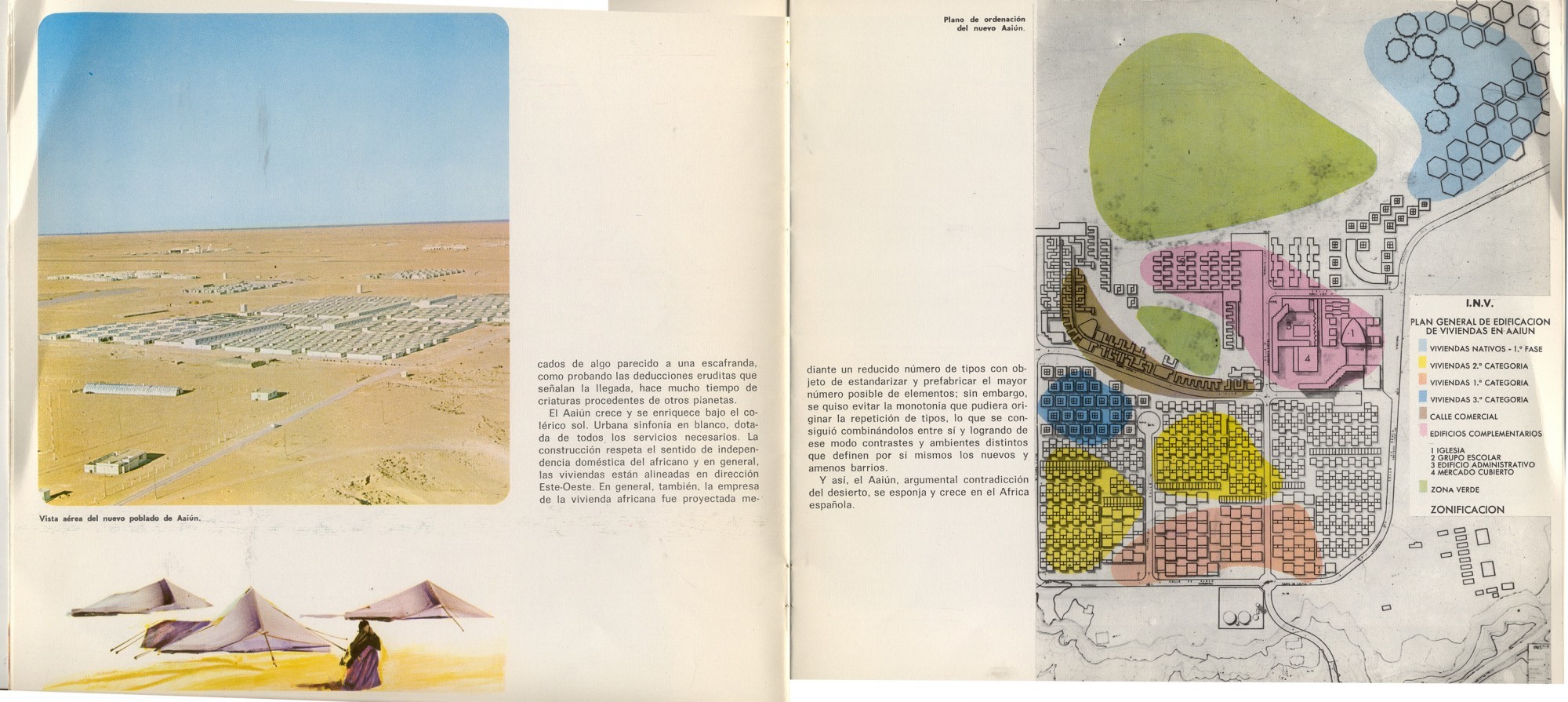

(Carrero Blanco May 16th, 1966)

Nuevas 'jaimas' de ladrillo y cemento, dotadas de todos los servicios, se alzan ahora en el desierto en zonas perfectamente urbanizadas. La civilización exige bases sedentarias [Brand new brick and concrete tents, equipped with all modern amenities, are now rising in the desert in perfectly urbanized areas. Civilization demands sedentary settlements.]

(Estalella 1966)

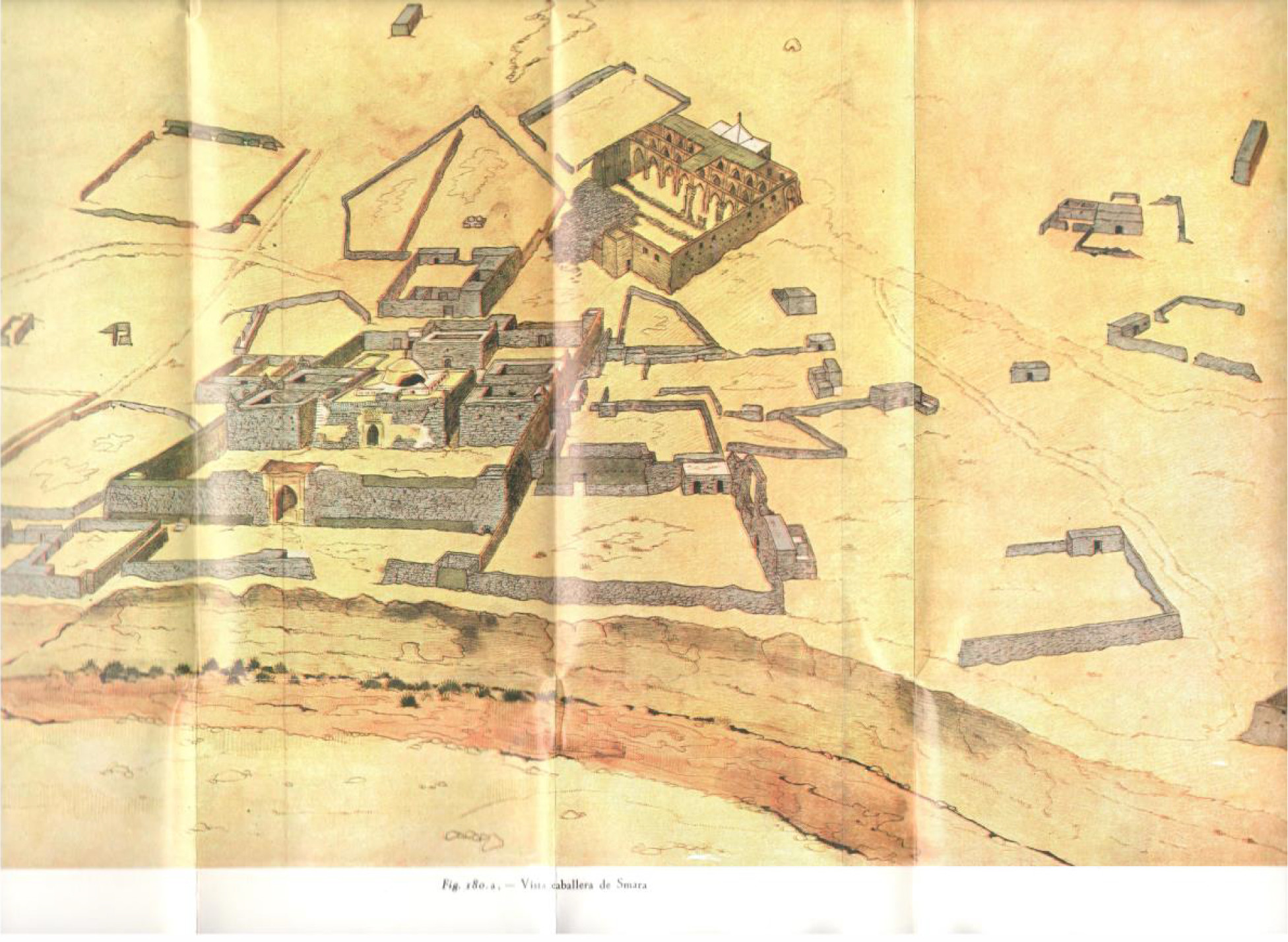

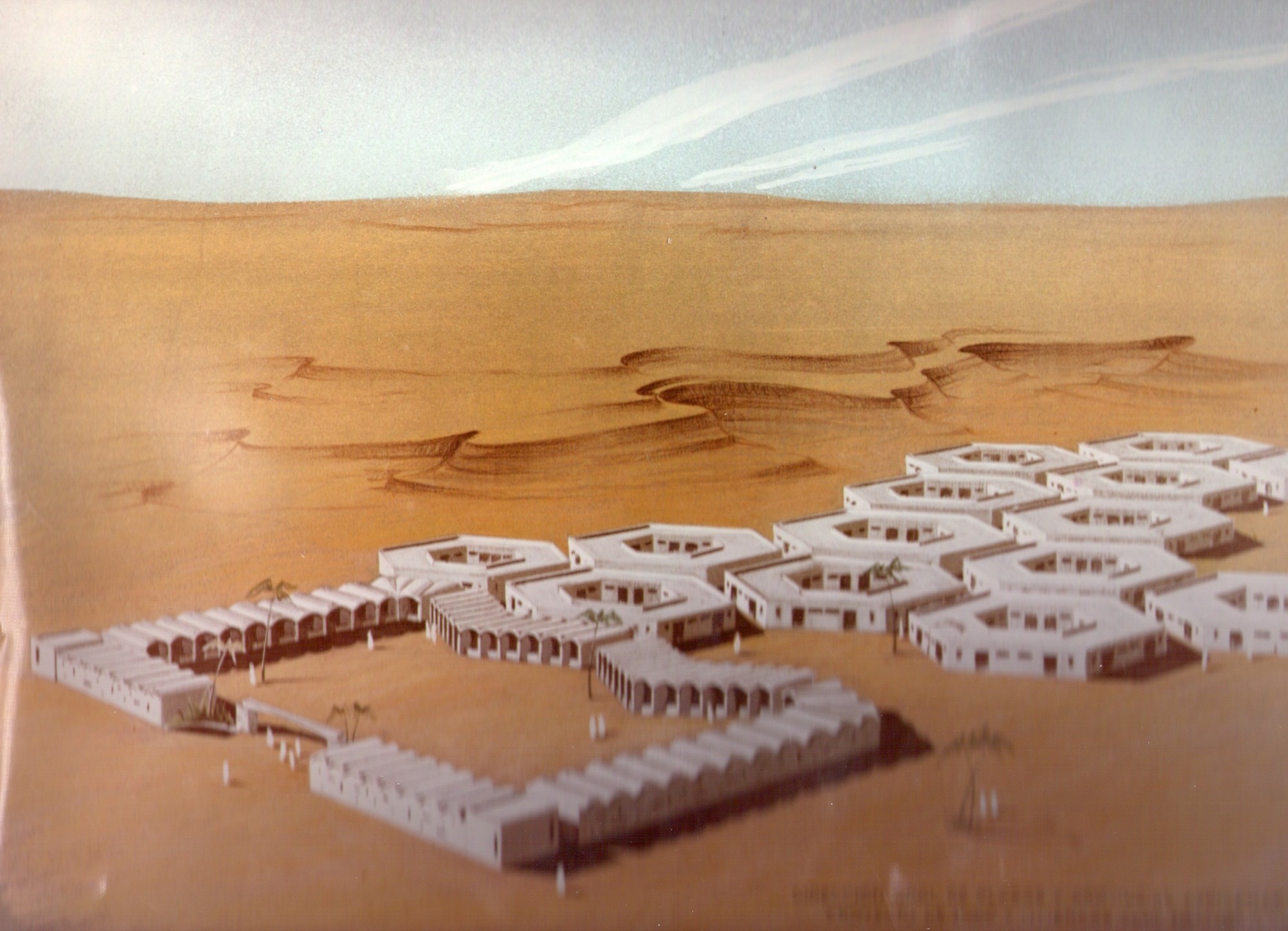

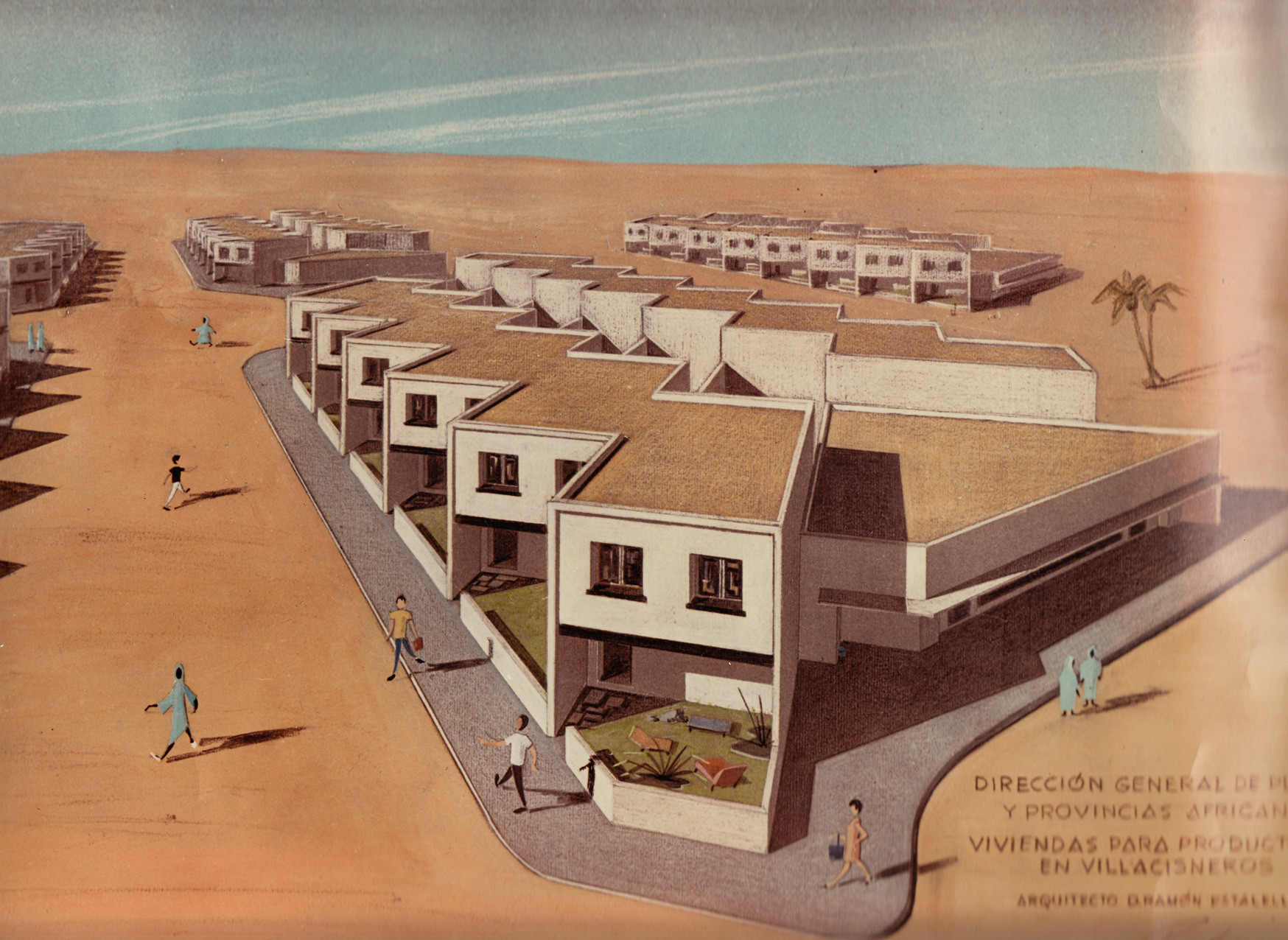

The first locution by Admiral Carrero Blanco (Sub-secretary Minister for the Government Presidency) at a 1966 visit to Laâyoune, as well the following from one of the leading urbanists and architects of the regime, encapsulates the masquerading of resource extraction (and occupation) under a thick veil of altruistic development. Countering such narrative, Yolanda Aixelà-Cabré denounces the large public works and infrastructural efforts as form of "historiographical invisibility" for Spanish African colonialism promoted by Francisco Franco.

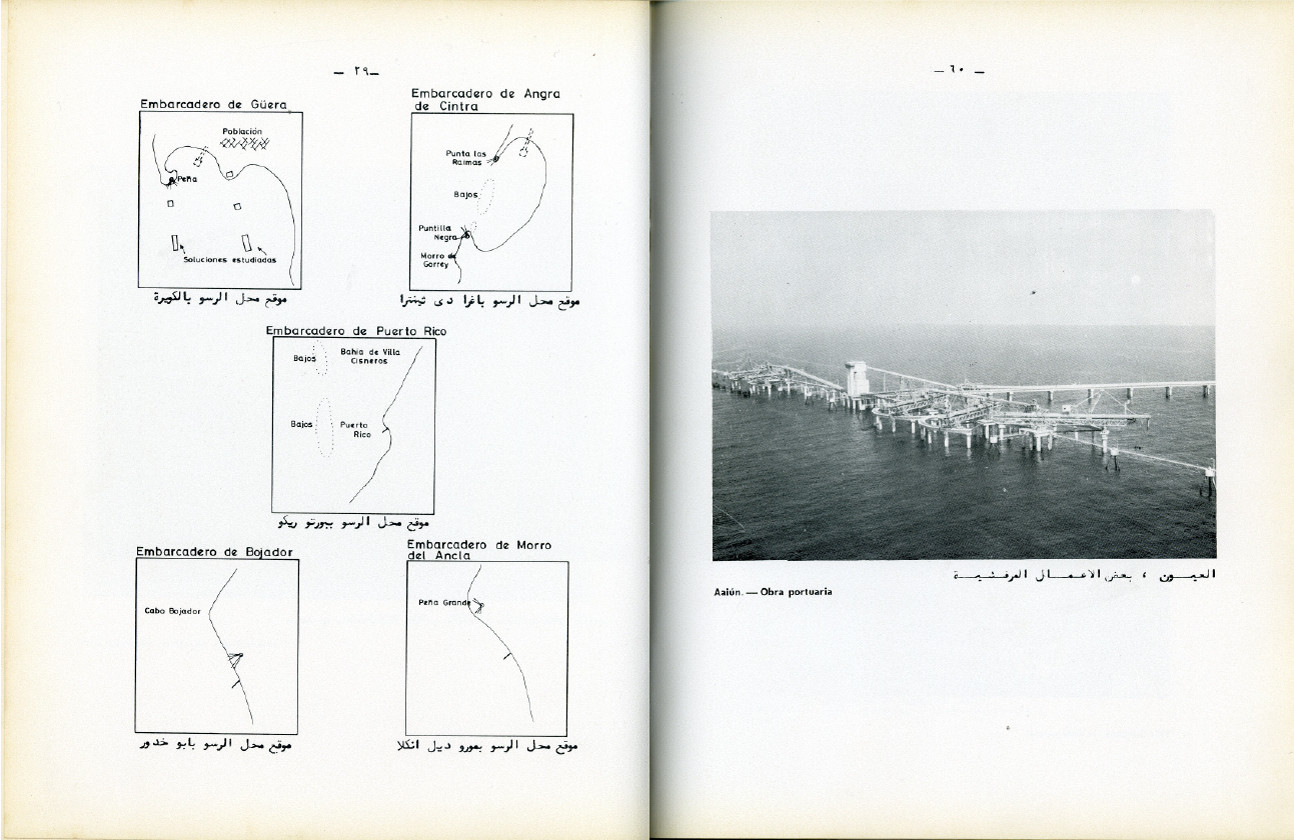

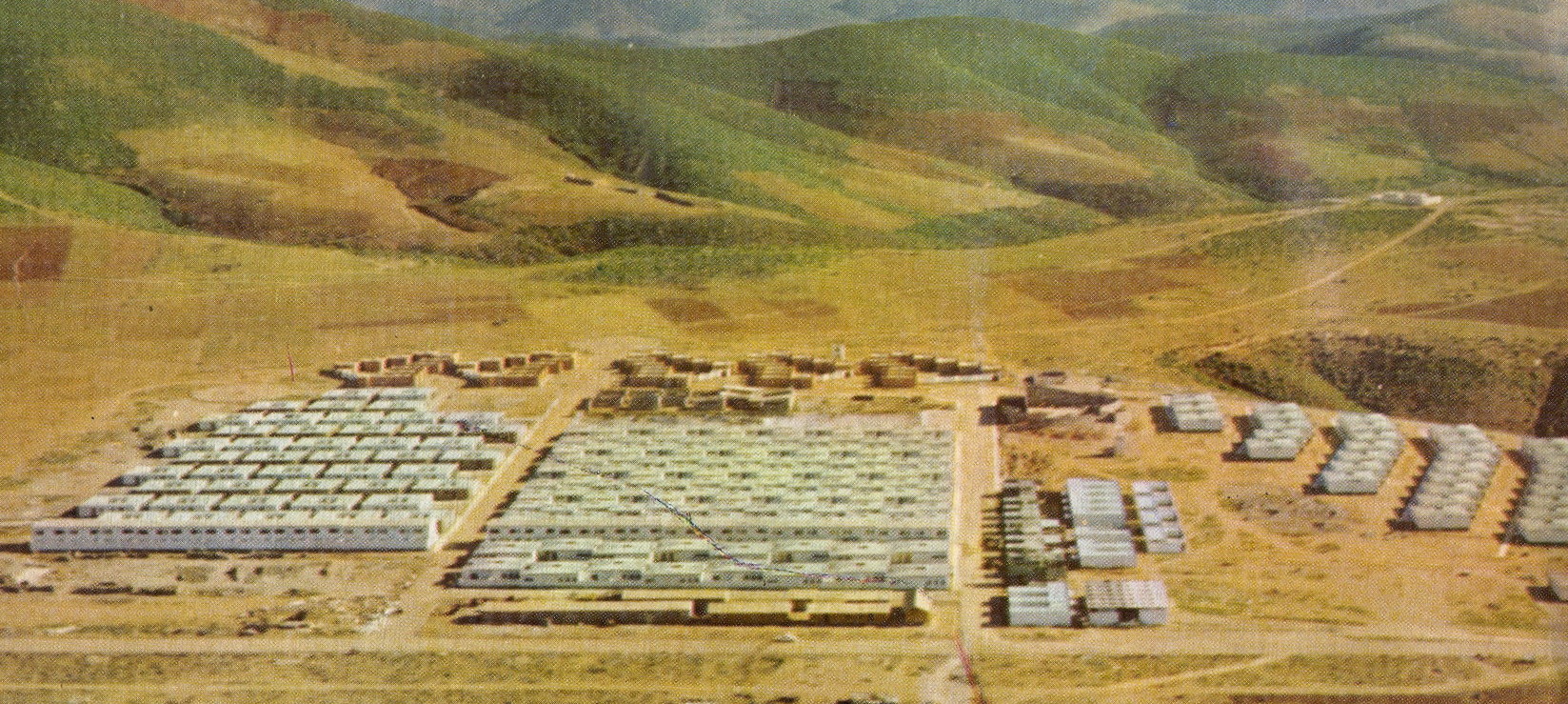

Under the pressure of rising decolonisation, the regime initiated alternative modes of occupation to maintain the extraction of valuable resources. The earliest efforts to assimilate nomadic populations entailed forcible eviction from traditional grazing grounds and/or trading routes, immediately followed by the aggresive promotion of sedentary settlements away from resource rich areas. As part of this process, cabilas (indigenous tribal organisations) were disarmed and passes/IDs issued for communities crossing the borders between the French and Spanish occupied territories. The French franc and the Spanish peseta were later introduced as official currencies thereby creating a necessity to enter into labour- and resource-oriented relations to obtain means of settling the payment of taxes (a scheme was largely deployed in Sub-saharan Africa by France).

The imposition of administrative structures in Ifni and (what was then called) Spanish Sahara provinces was later compounded by the creation of experimental urban plans, the construction of harbours, airports and markets. As a way to further entice nomadic communities into sedentary settlements, newly established colonies expressely included indigenous elements into the spatial and decorative design, which included schemes like rent-limited public housing. Spain’s African colonies offered mainland architects, urbanists, and ultimately Spanish modernity at large a fertile ground for experimentation. It is no accident that the first ever modern Spanish General Urban Plan by Pedro Muguruza - celebrated for being the first implementating zoning laws - was not for the Spanish Capital, but rather Tetuan in the African Protectorate.

…

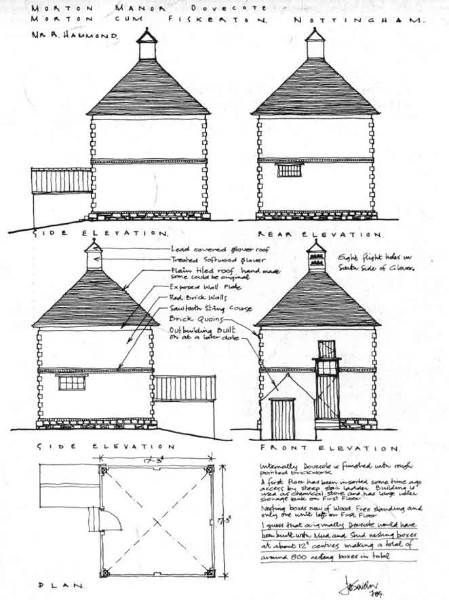

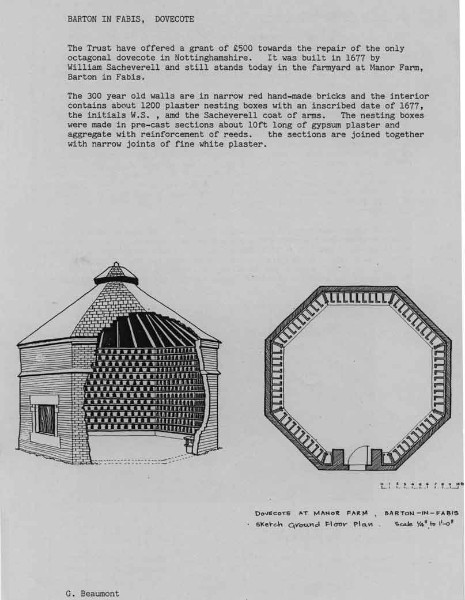

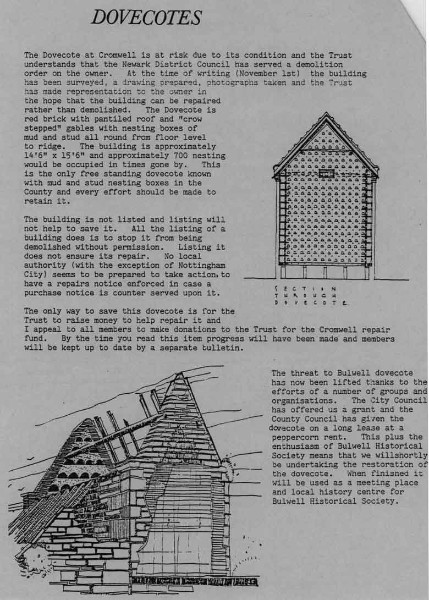

Dovecotes

Dovecotes

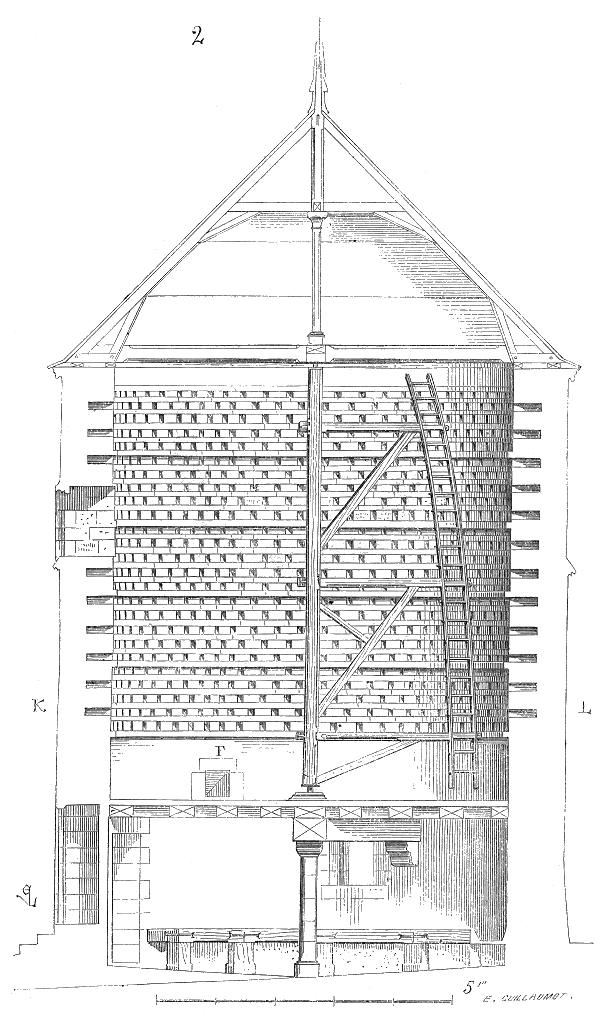

Dovecotes are structures that house pigeons or doves, and are designed in such a way that the bird droppinngs can be collected to use as fertiliser for nearby crops.

In Medieval Europe, dovecotes were symbolic displays of power, as well as a form of integrated breeding and fertilising. They were regulated by laws such as “droit de colombier”, a privilege only afforded to nobles and feudal lords. A conspicuous feature in open rural landscapes, often bordering villages, they were outside of stylistic or structural requirements in regular buildings, usually more attractive and better constructed than the peasant homes Since antiquity, dovecotes through the Middle East and Europe have served as breeding structures which provided rich fertiliser for the surrounding crops. Dovecotes themselves replicated cliffs and rock ledges which are used for roosting and breeding in the wild. Farmers were careful to keep their dovecotes clean, whitewashed, and perfumed in order to increase the birds’ attraction to their dwellings. An average dovecote with around 1,000 nesting cells produced up to 12 tons of manure annually, enough to fertilise 1,500 fruit trees or vines.

We look to these traditional knowledges and architectural marvels at a time where soil impoverishment (due to intensive agriculture and chemical fertilisers) is considered a major environmental risk.

This project is in development.

…

Arboriculture

Arboriculture

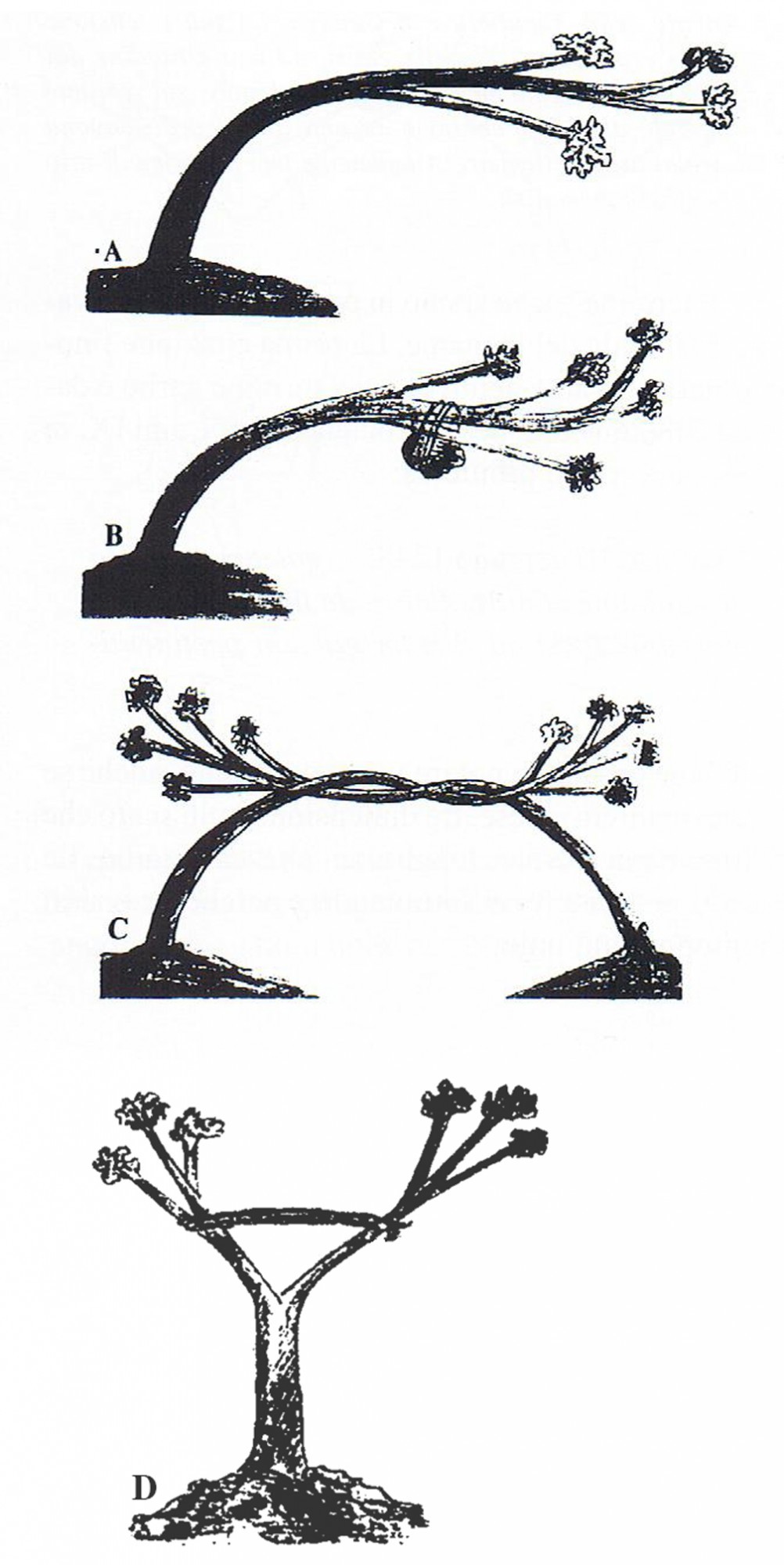

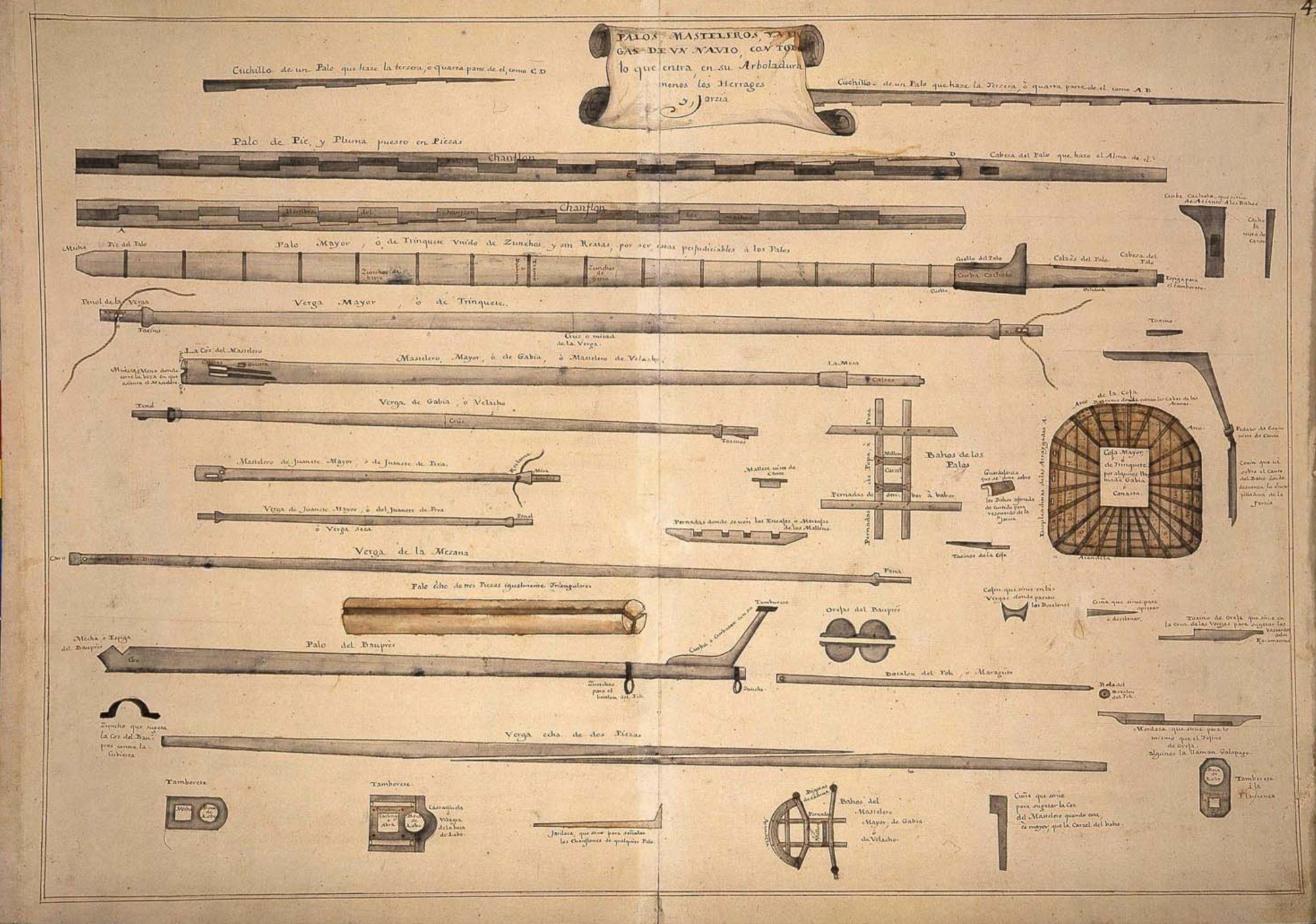

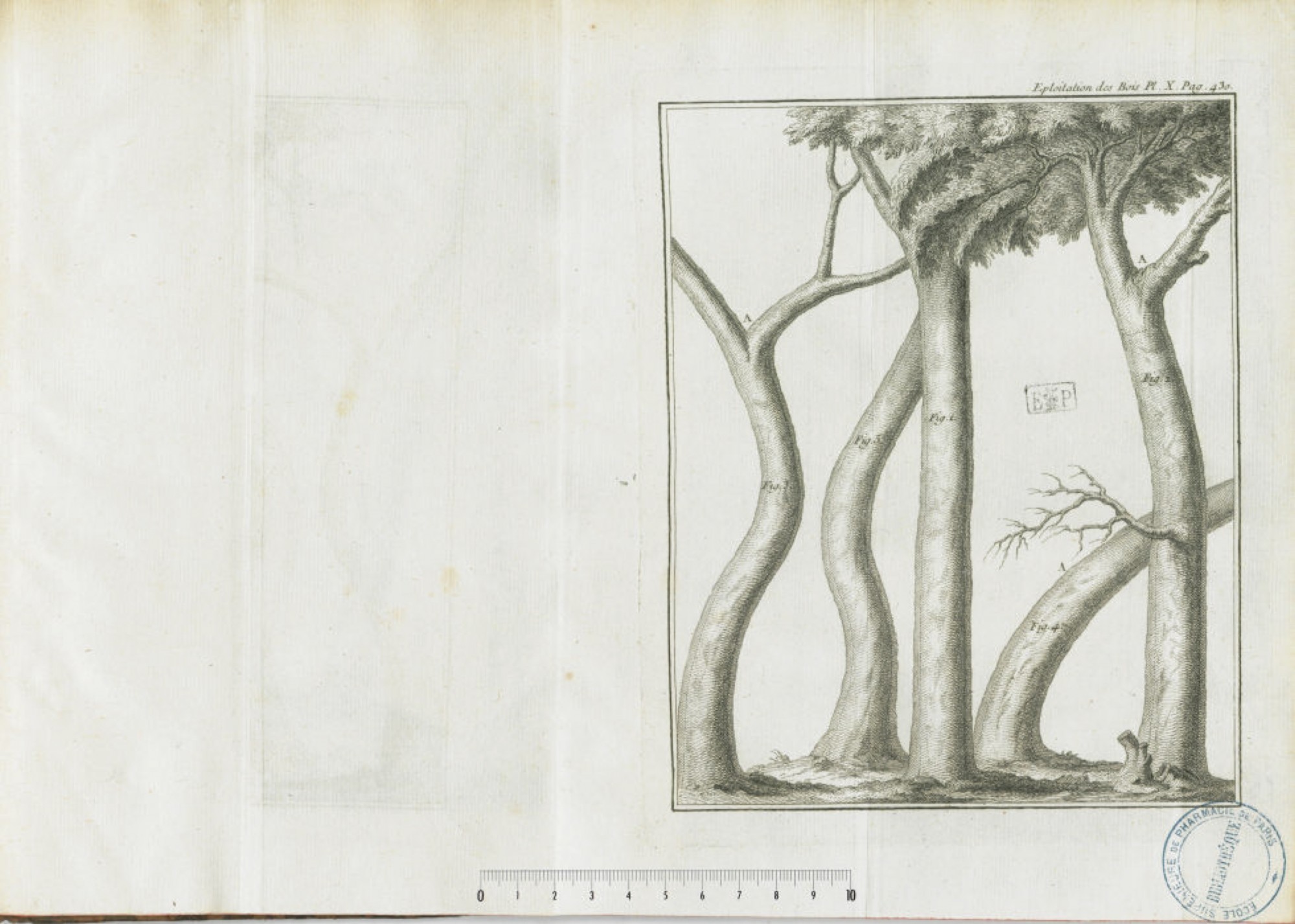

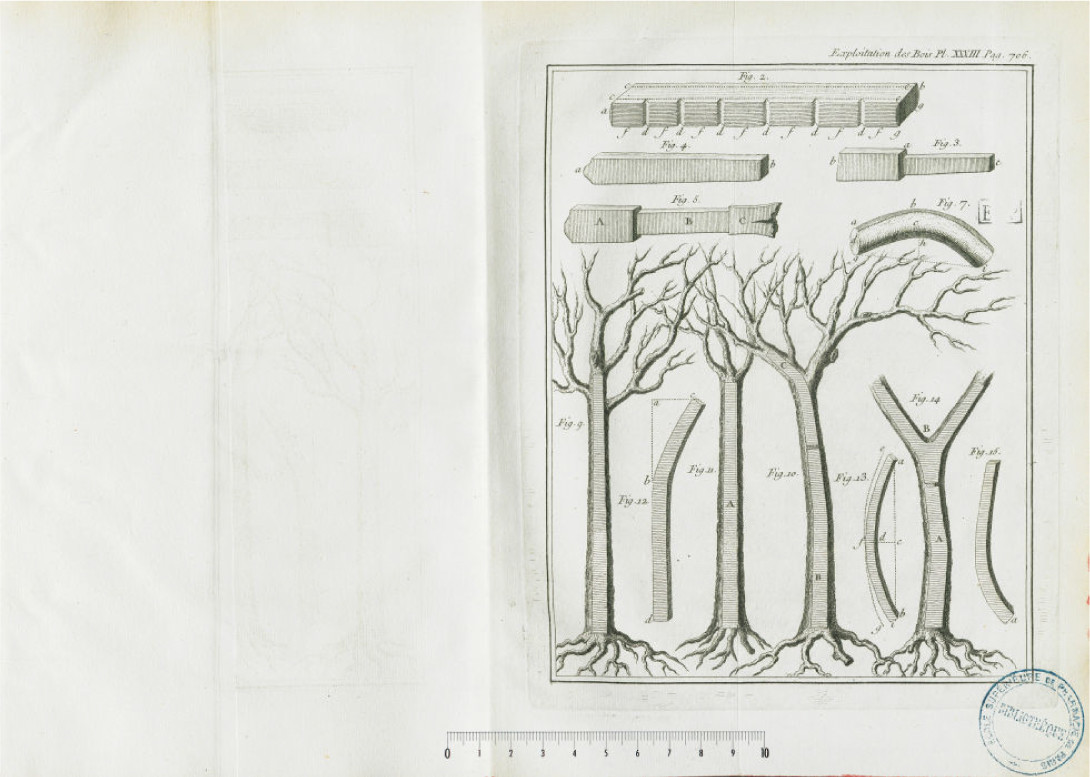

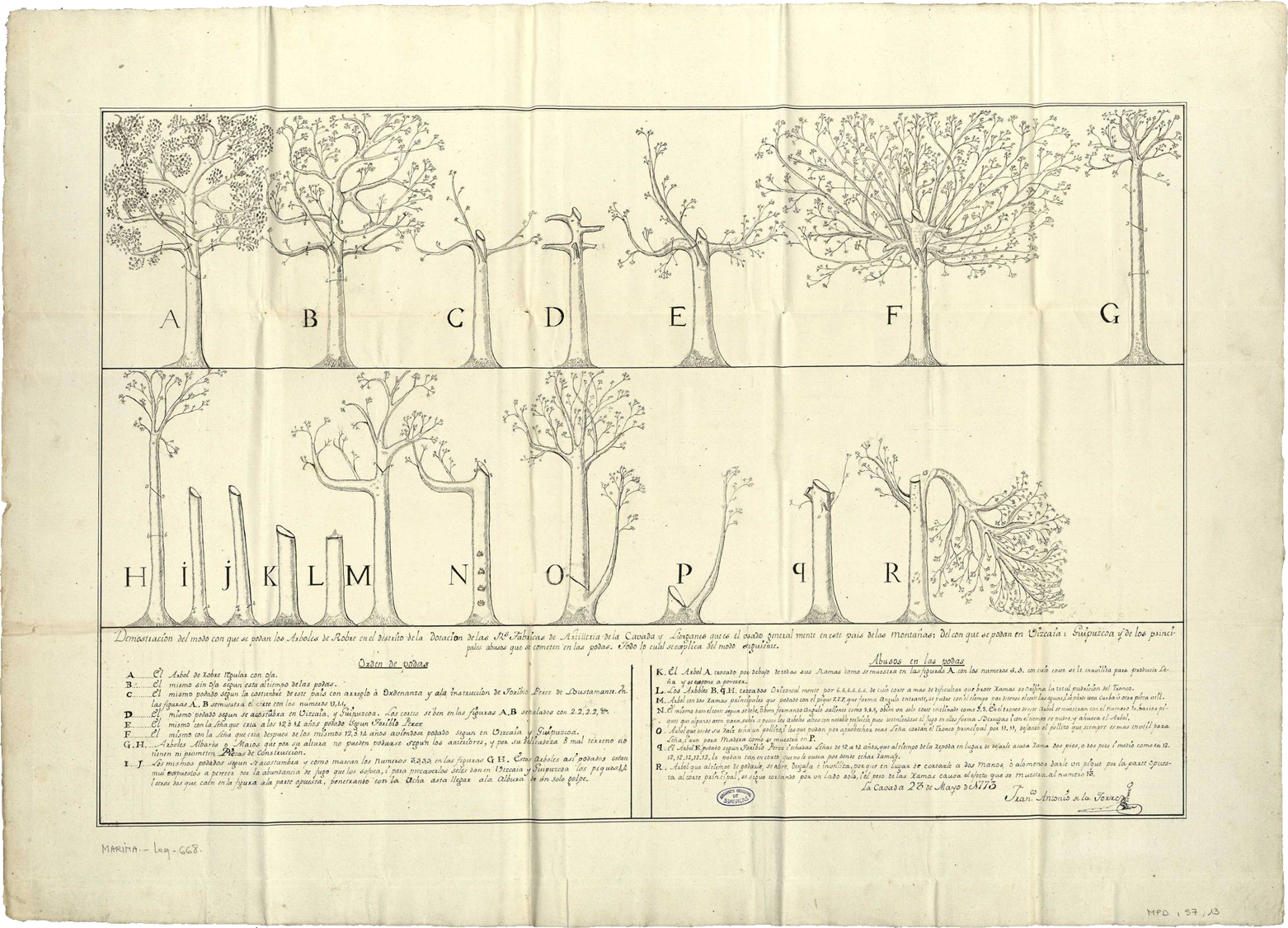

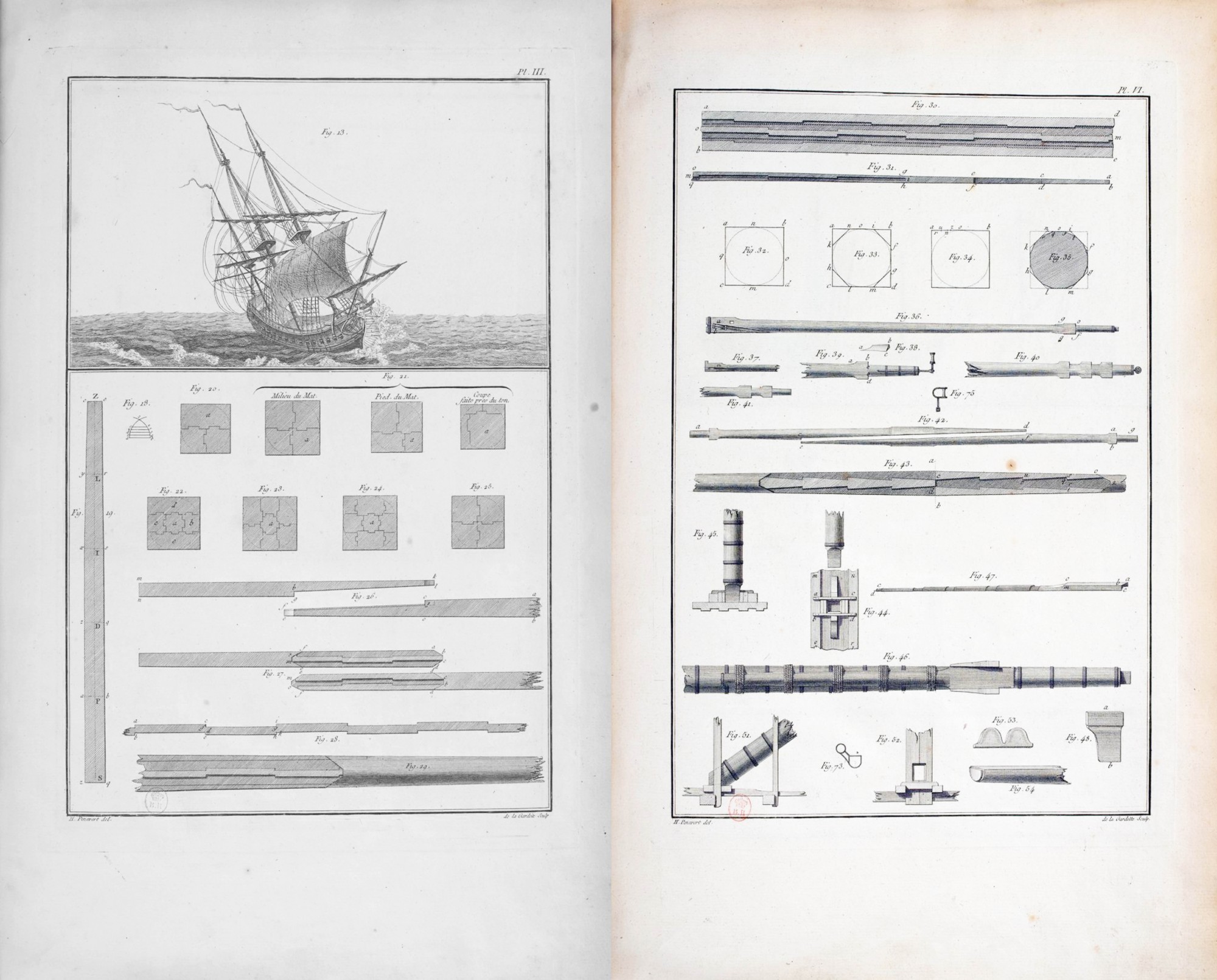

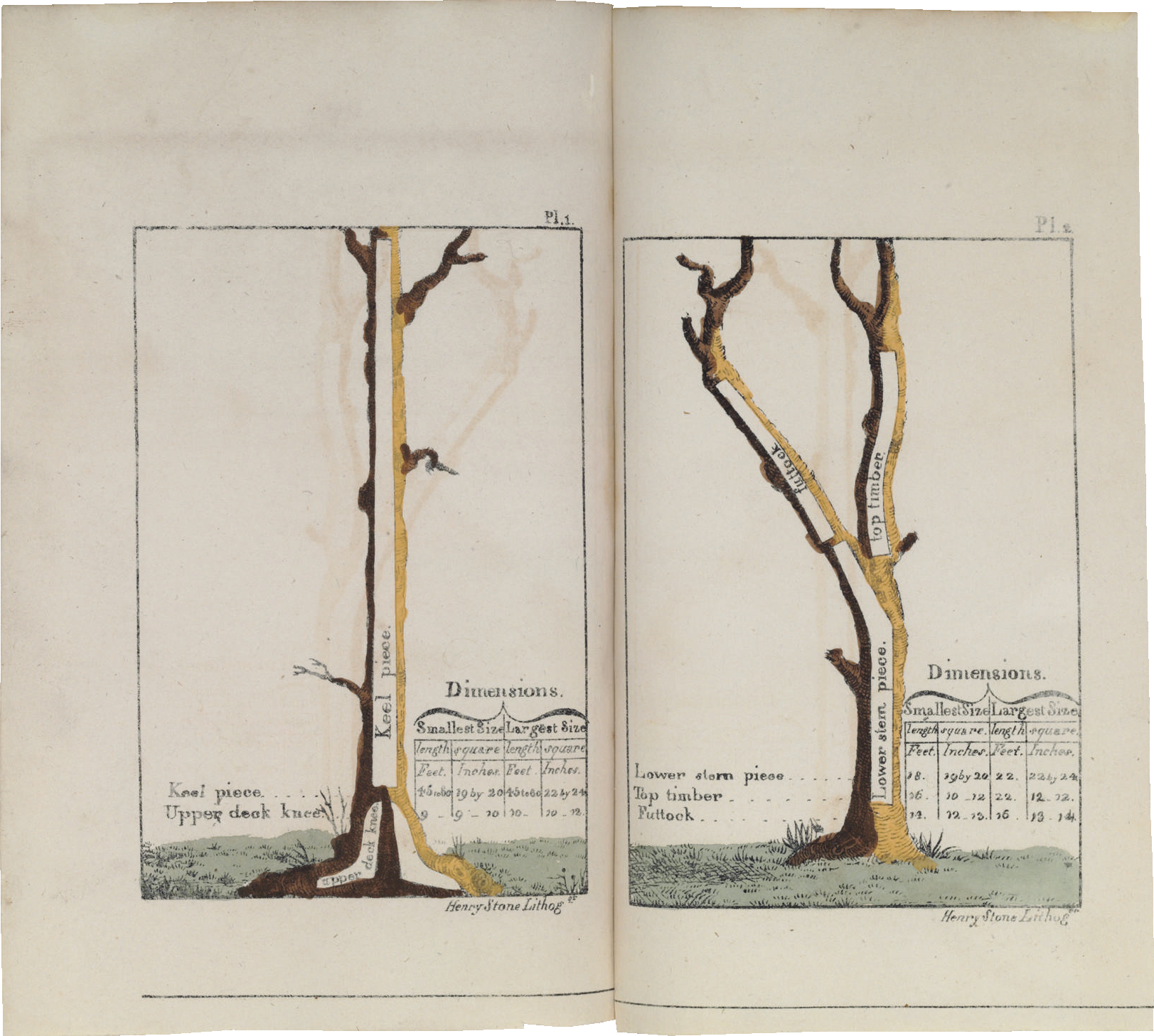

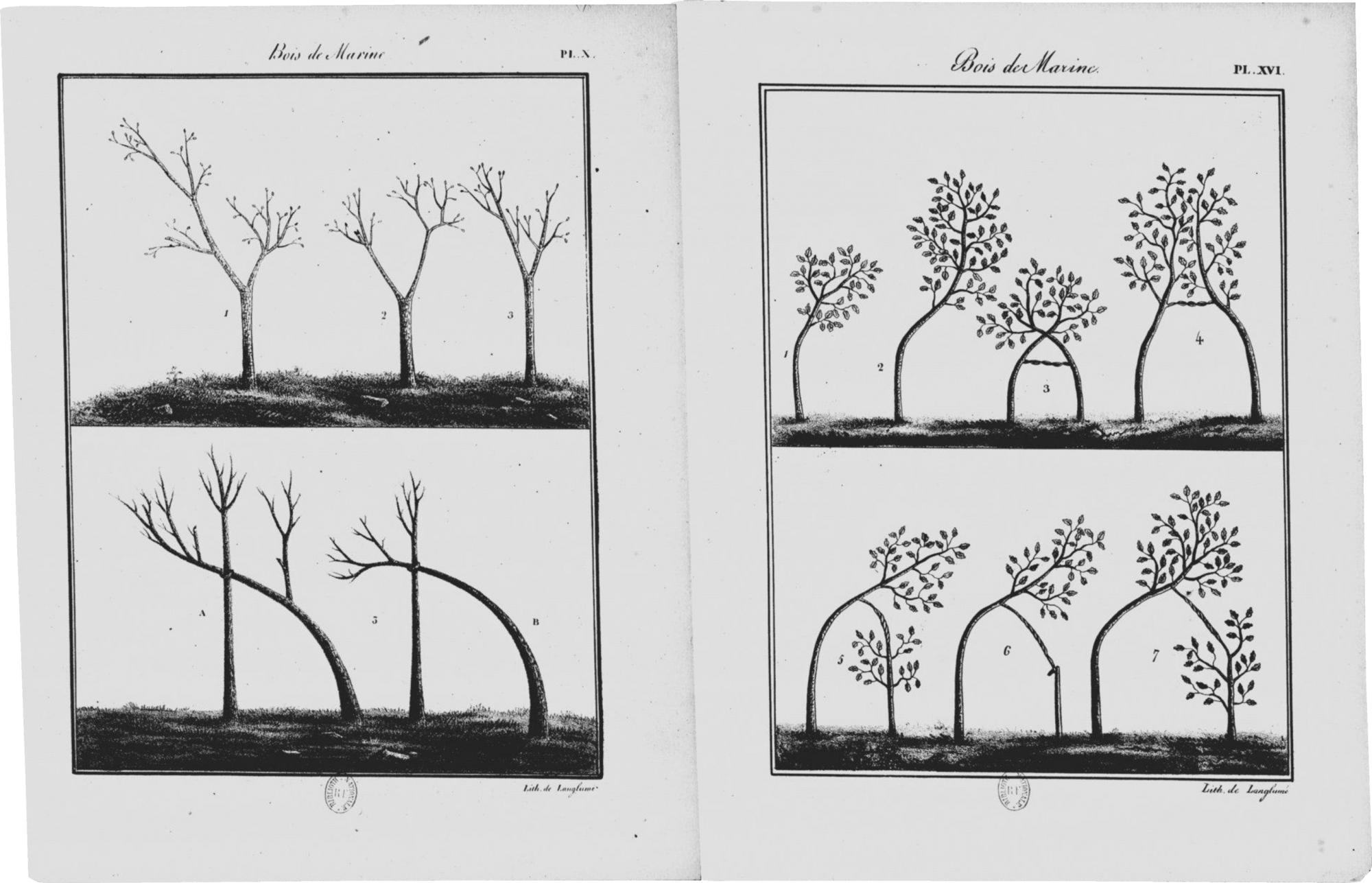

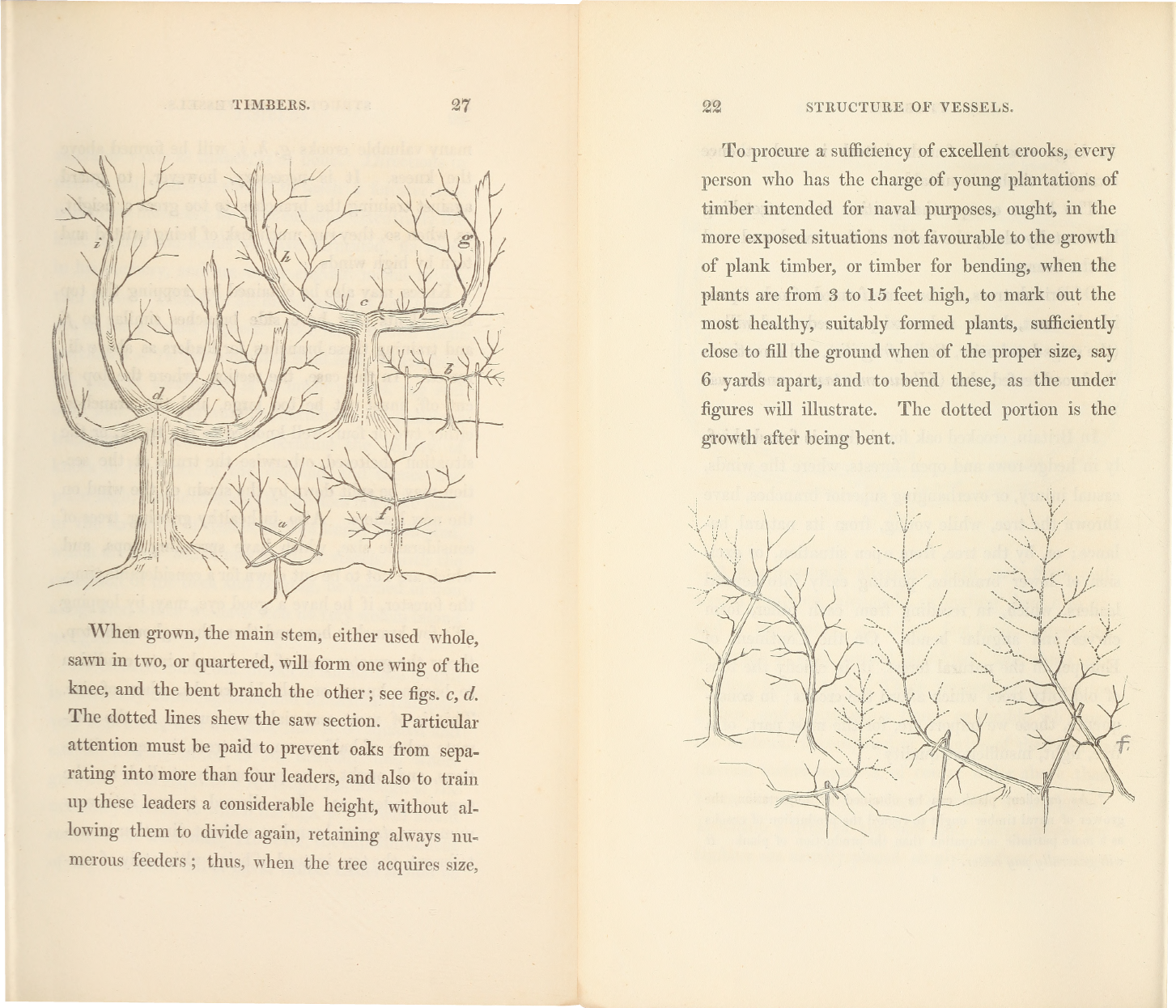

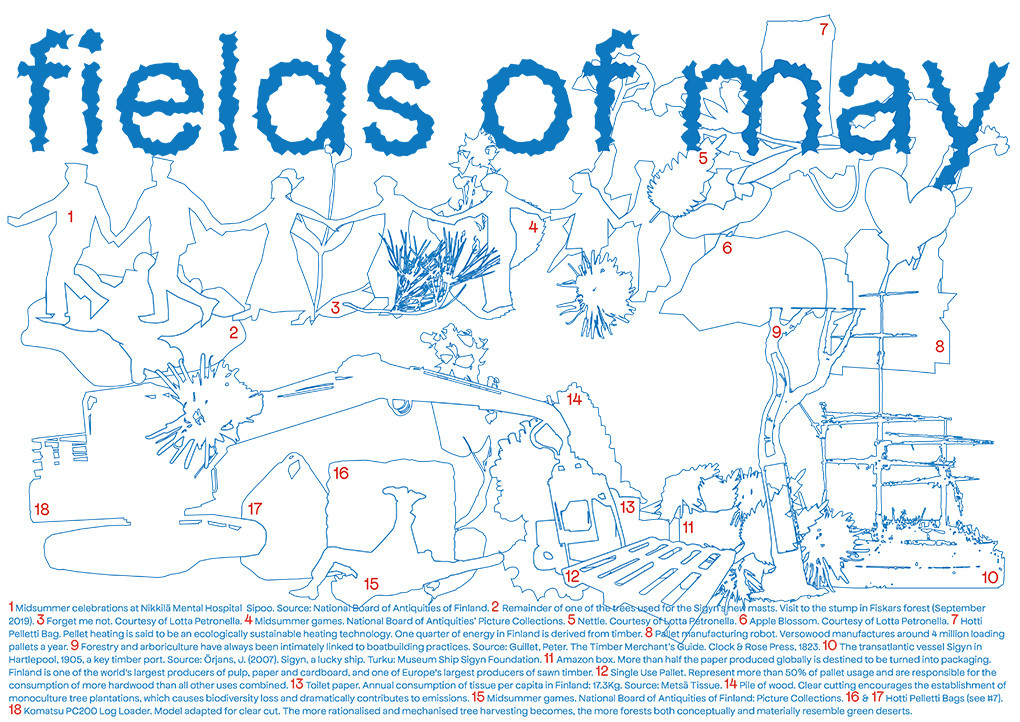

A: Oak trained without weight. B: Oak trained with weight. C: Two crossed oaks. D: Forcazzo: branches trained to grow apart from each other. Ciciliot, F. (1999) 'Garbo Timber', Proceedings of the 7th International Symposium on Ship Construction in Antiquity, Athens.

…

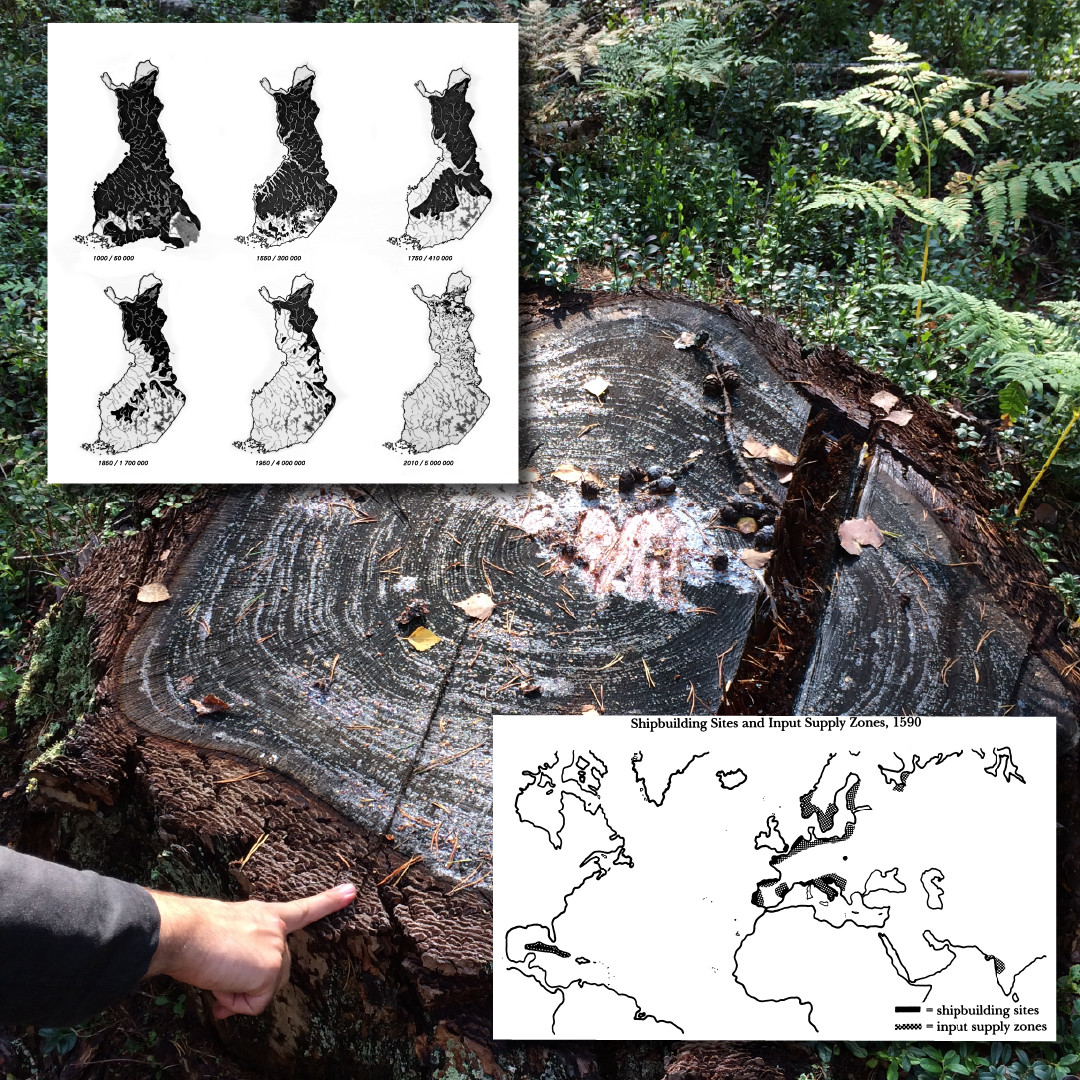

Forestry

Forestry

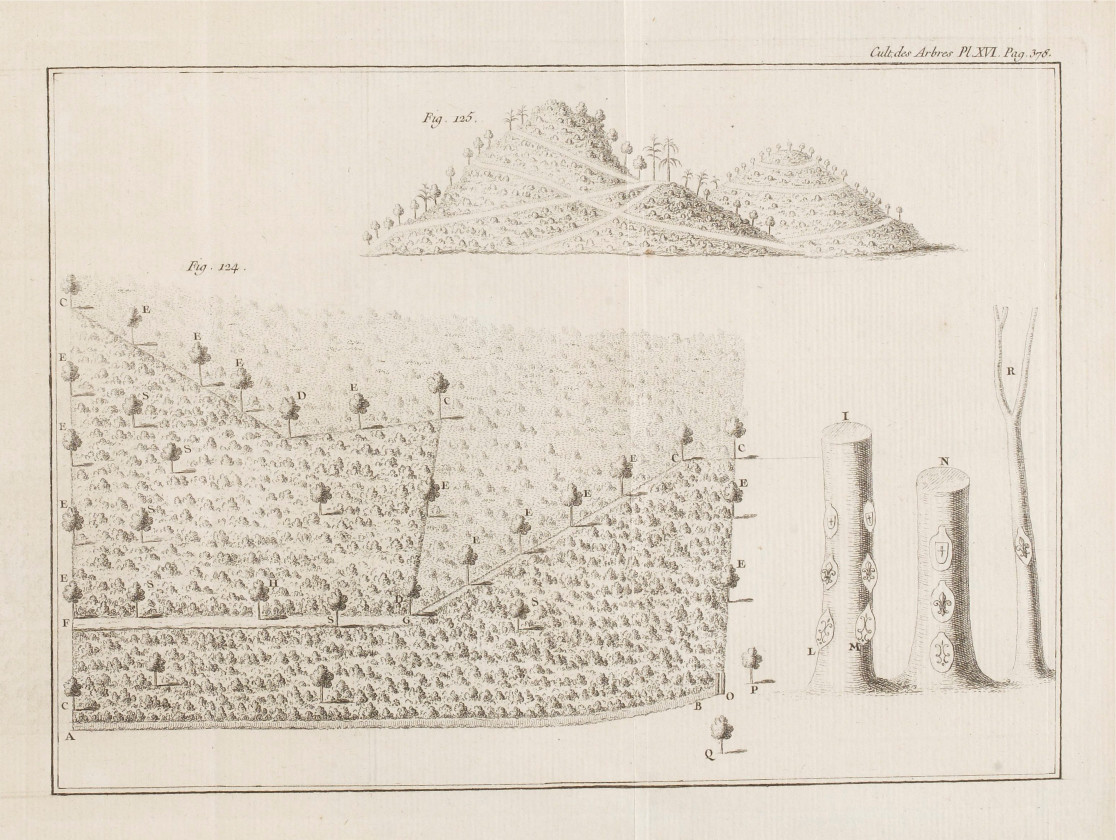

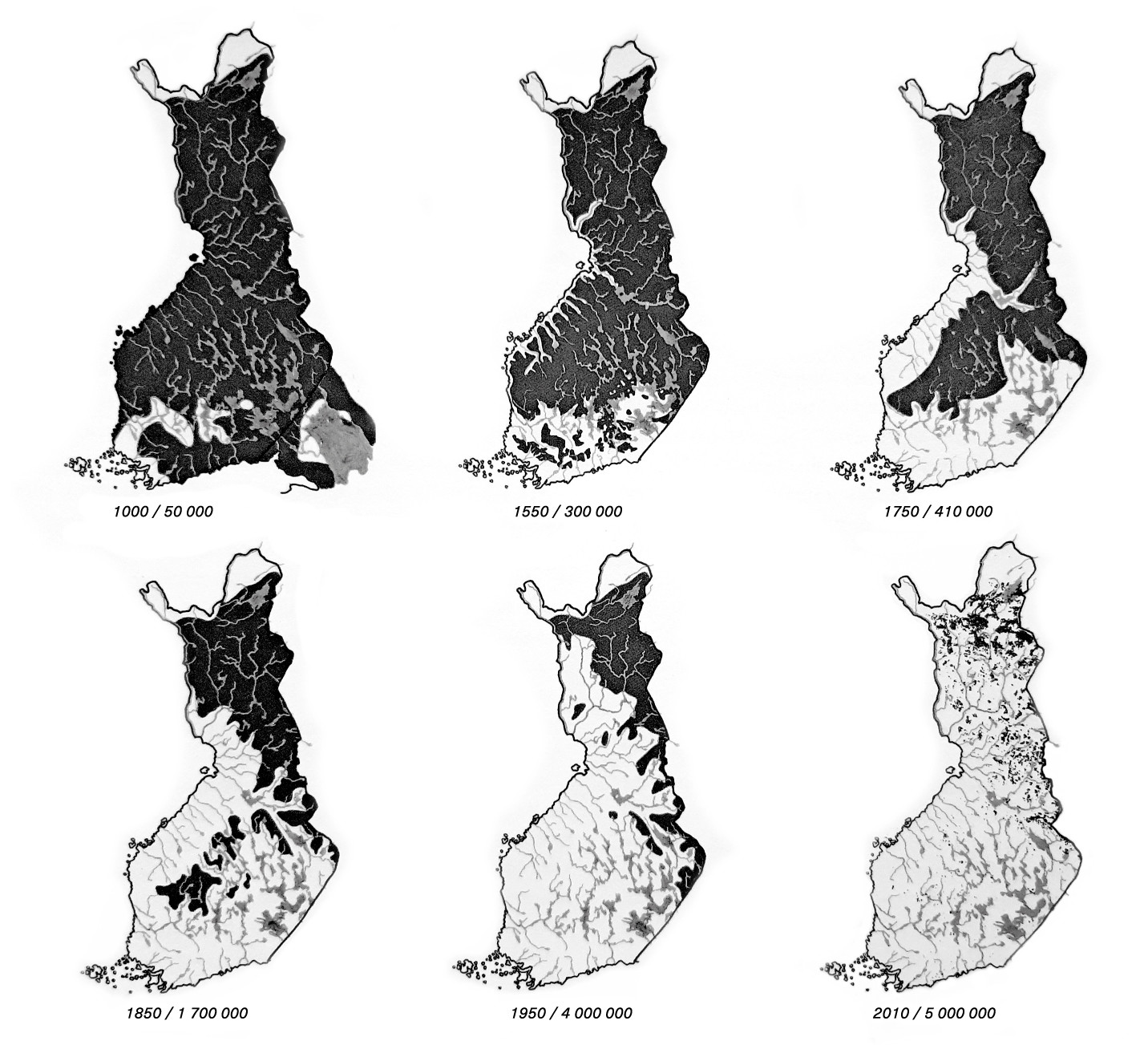

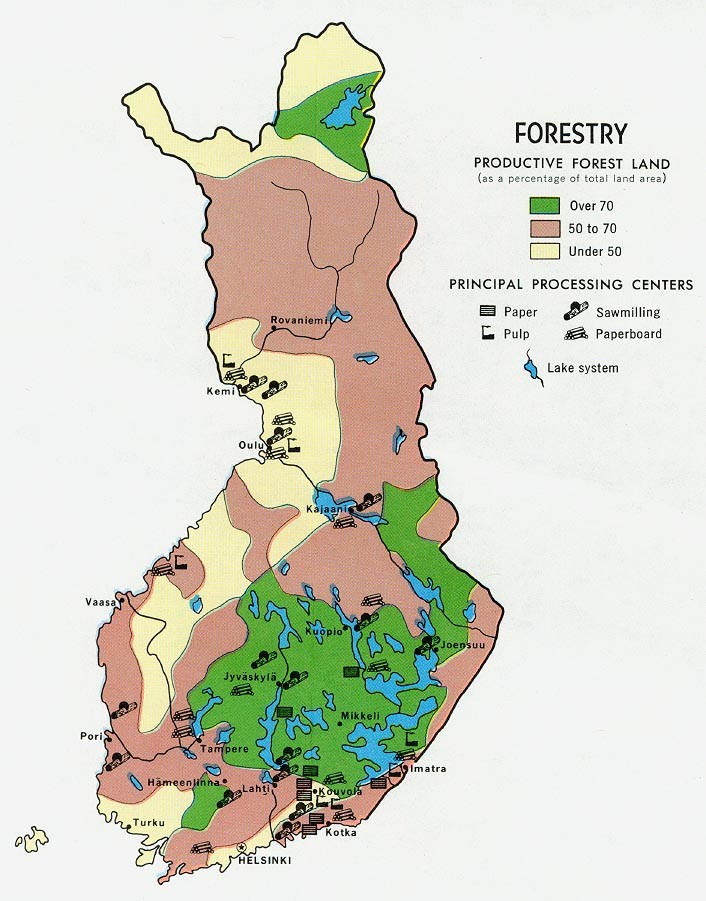

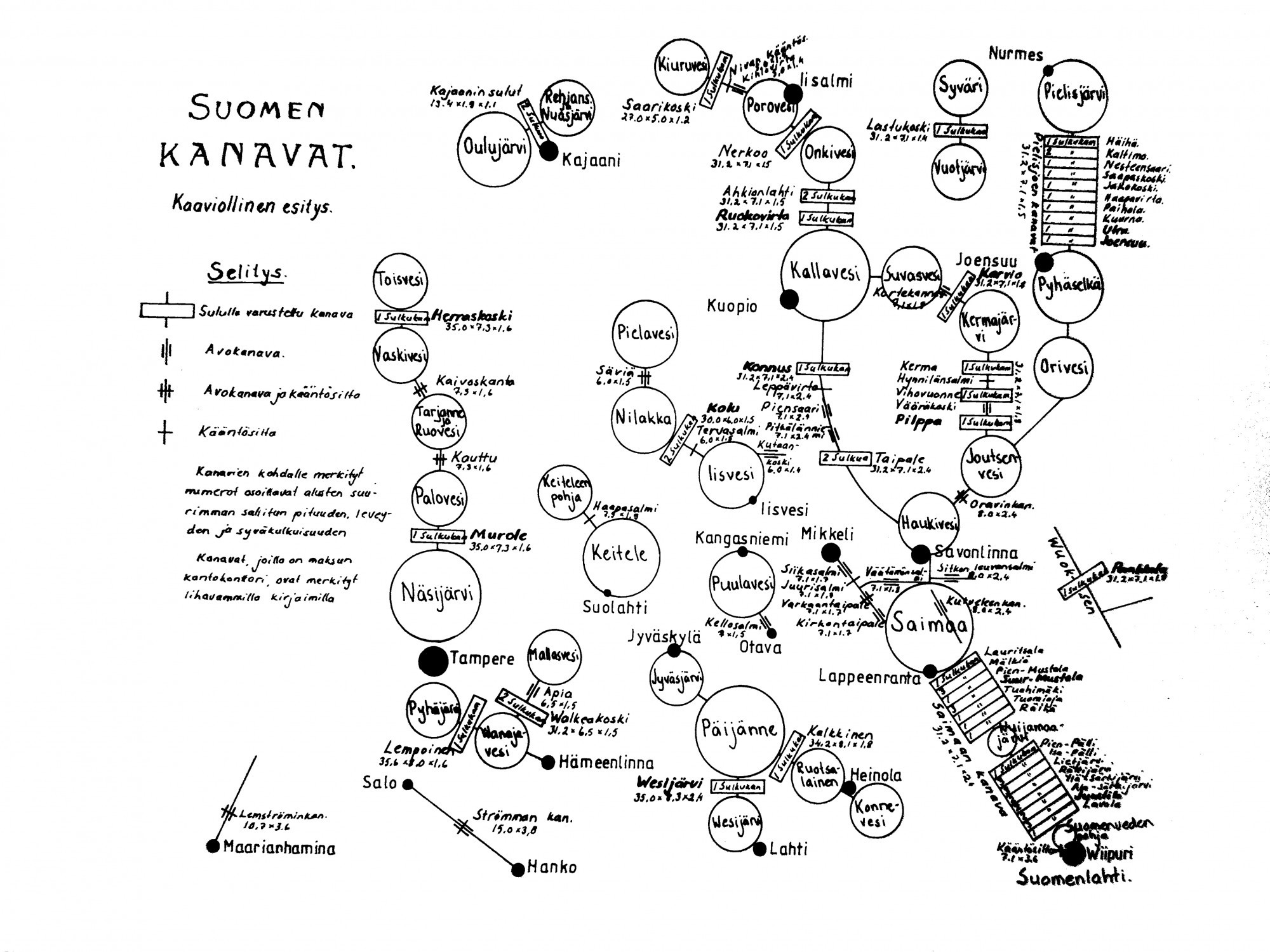

The wider global trend towards financialisation and the switch from agricultural to monetary economies emphasises notions of ‘exchange value’. Eino Saari (1894-1971) is said to be one of the founders of forest economics in Finland. He pioneered the first national wood utilization survey in the world – the birth of forest valuation. This could be understood as the development of biological-mensurational research which enables the application of economic theory and facts to biological and technical conceptions. In 1966, Kullervo Kuusela of the Finnish Forest Research Institute stated: “the age of planned development of forest resources is about to begin” (Edwards 1968, 155). Kuusela’s statement points to the importance of early national wood utilization surveys within a genealogy of ecosystem services.

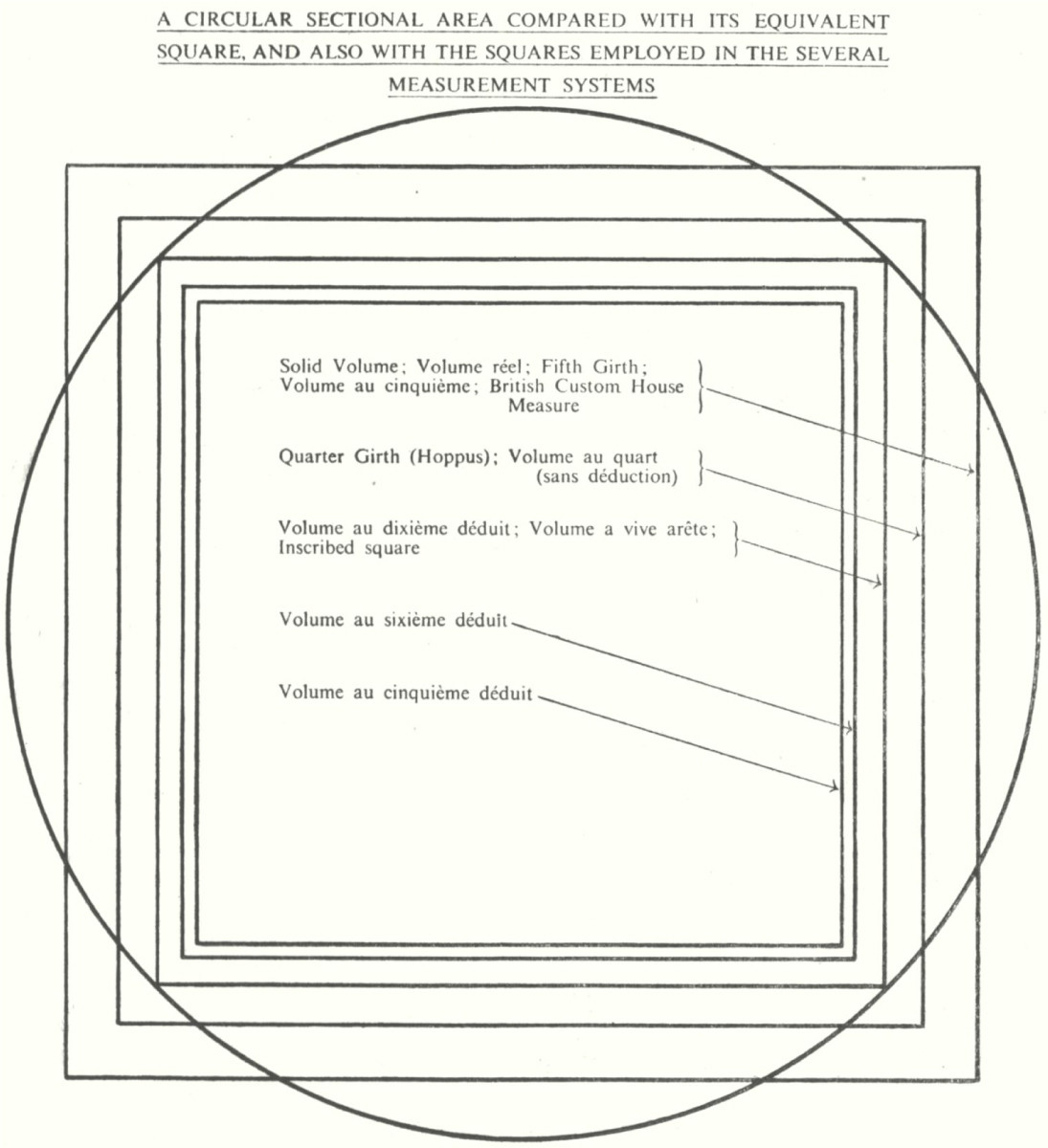

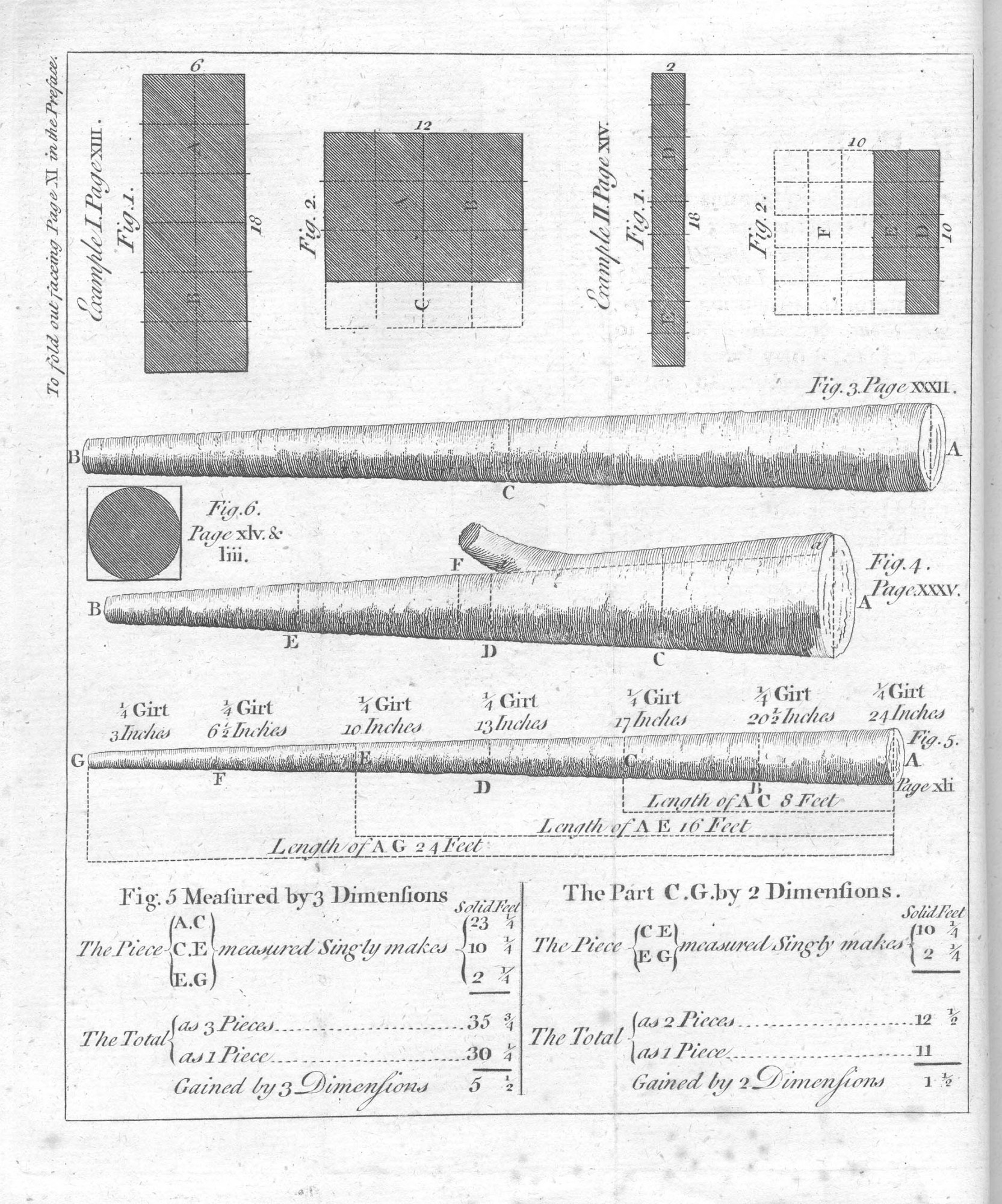

Central to planned development is forest modelling, one of the oldest forms of mathematization of risk calculation and the calculation of ‘worth’. The birth of forest valuation is, according to the economist John Maynard Keynes, the link between the present and the future, the latter being “perfidious” and threatening (Esposito 2011, 11). Industrial forestry thus conquers the perfidious future through planned harvest, determined maturity, yield calculation and other predictions. Forest modelling, in its conquest to assuage future uncertainties, systematises the forest as a set of variables within a formula, forever optimising itself, thus paving the way for its financialisation.

Text excerpt from:

Gallardo, Francisco, and Audrey Samson. Carboniferous Capitalism. HIAP. https://www.

hiap.fi/carboniferous-capitalism1/. Published 2020. Accessed November 10, 2020.

…

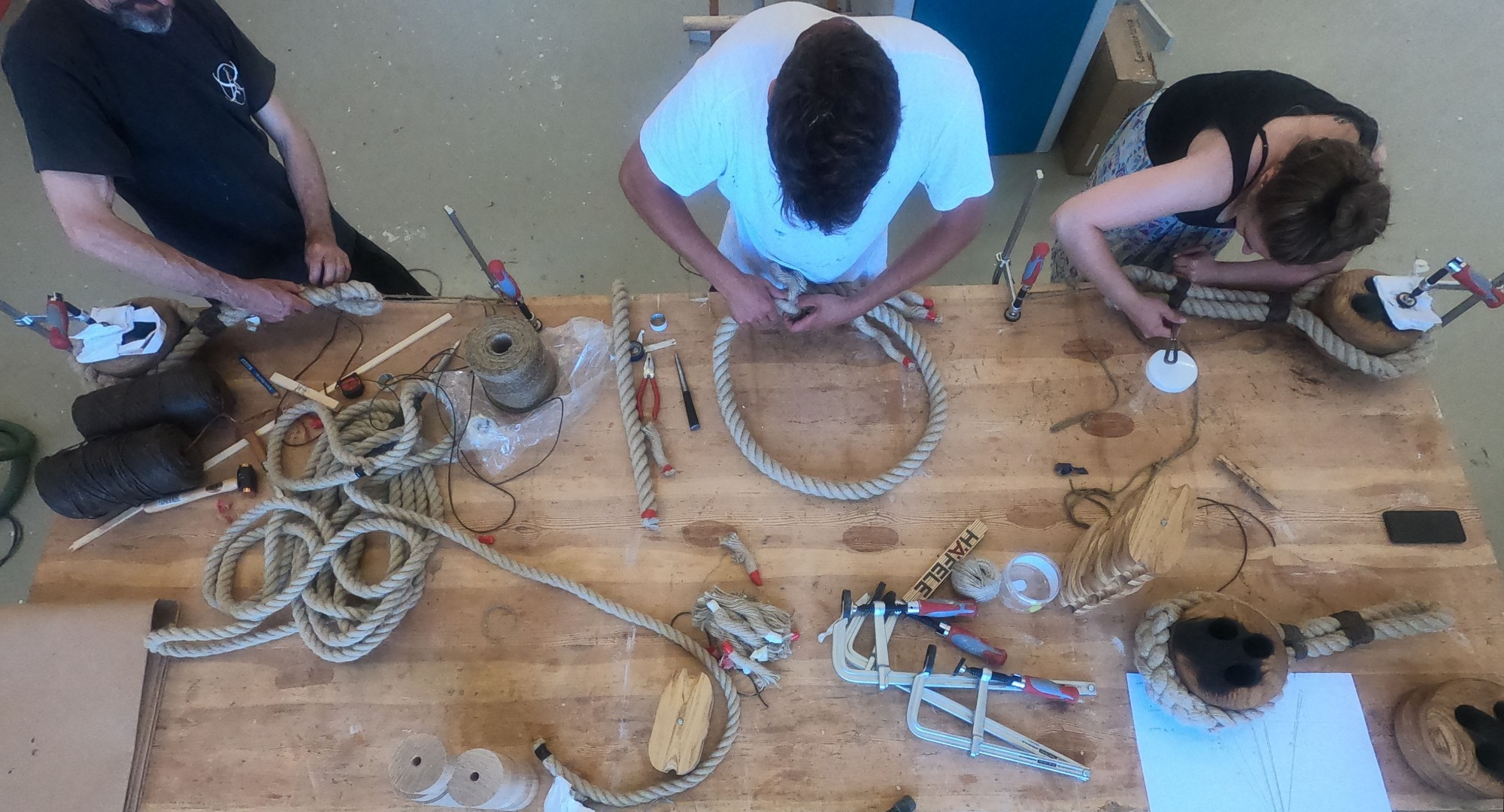

Tar

Tar

(Finnish Proverb: If alcohol, tar and sauna do not help, then the disease is fatal)

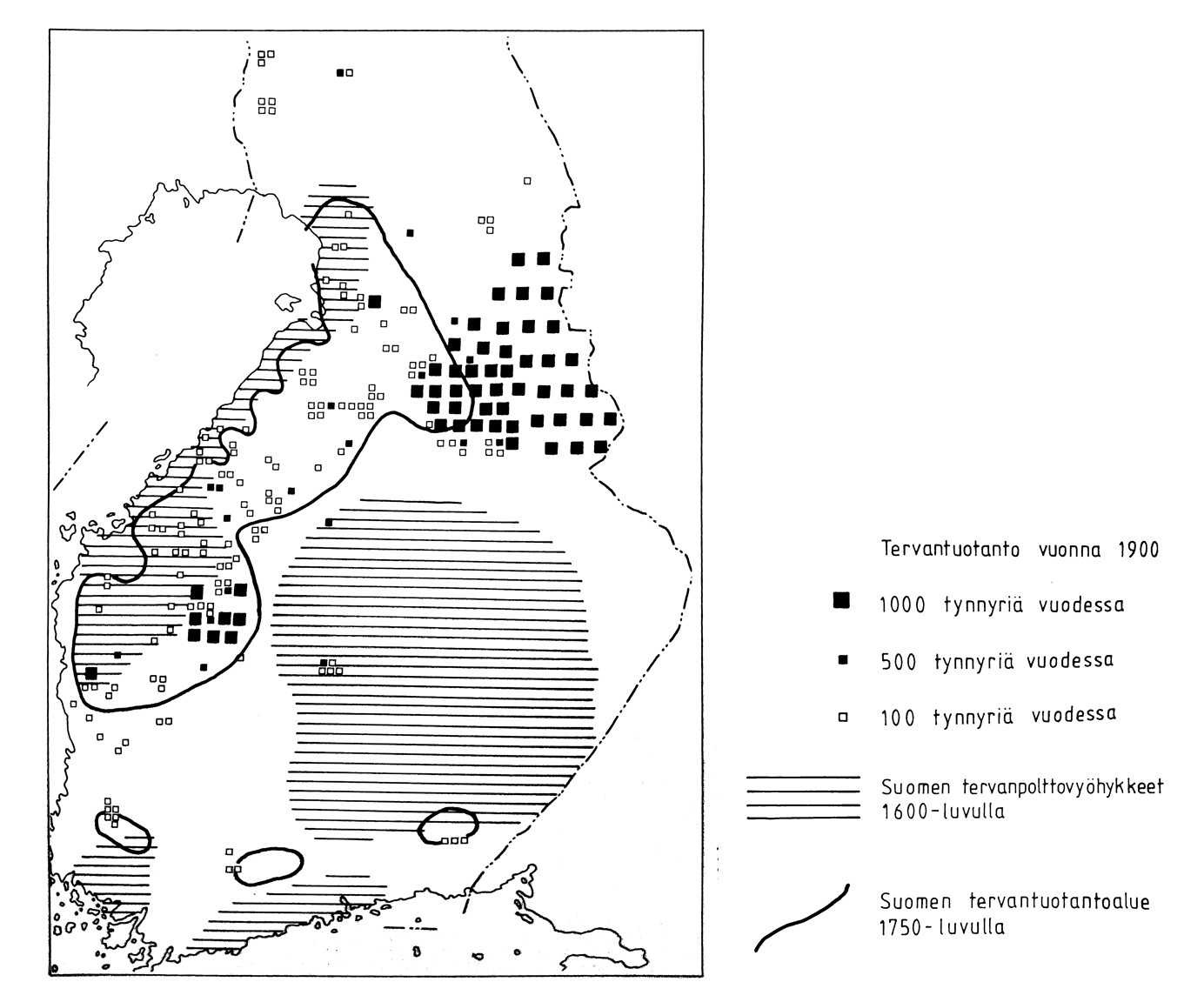

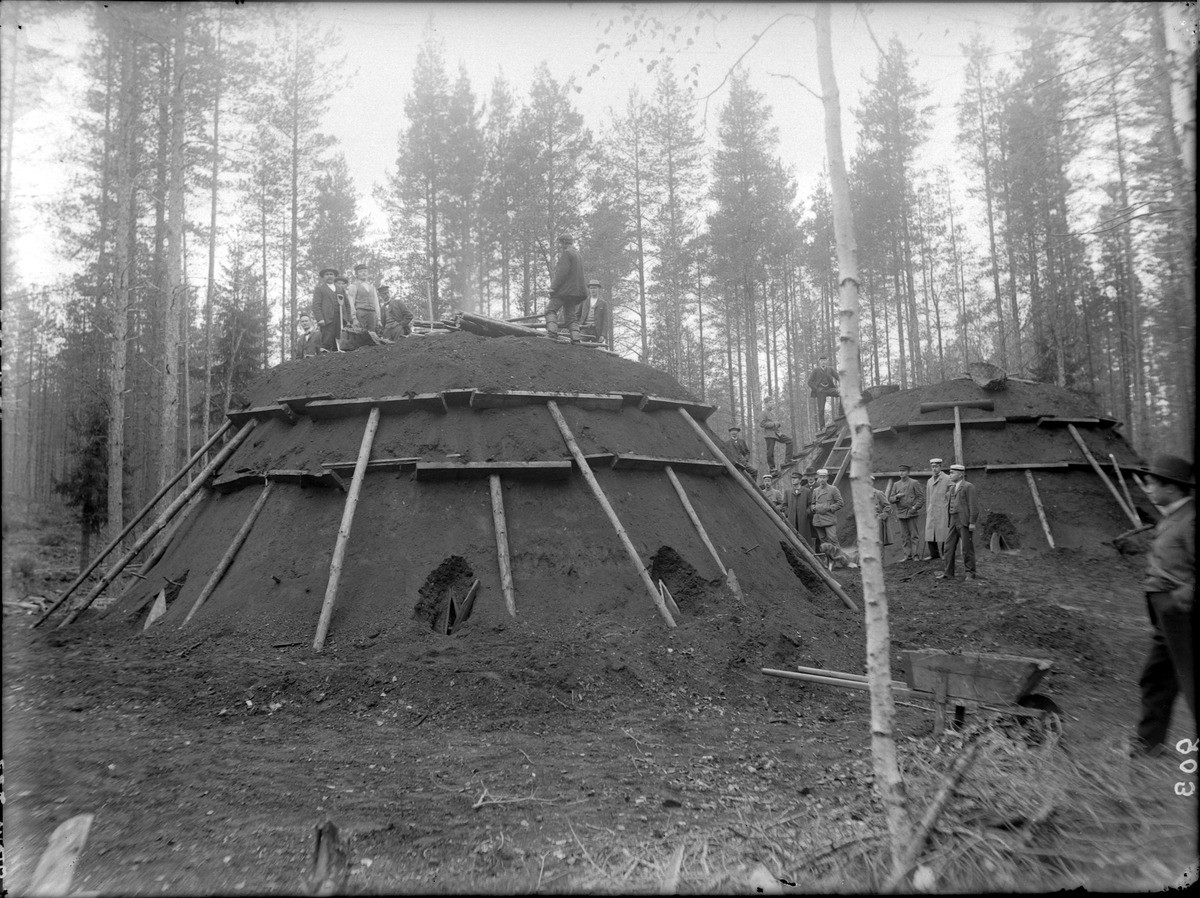

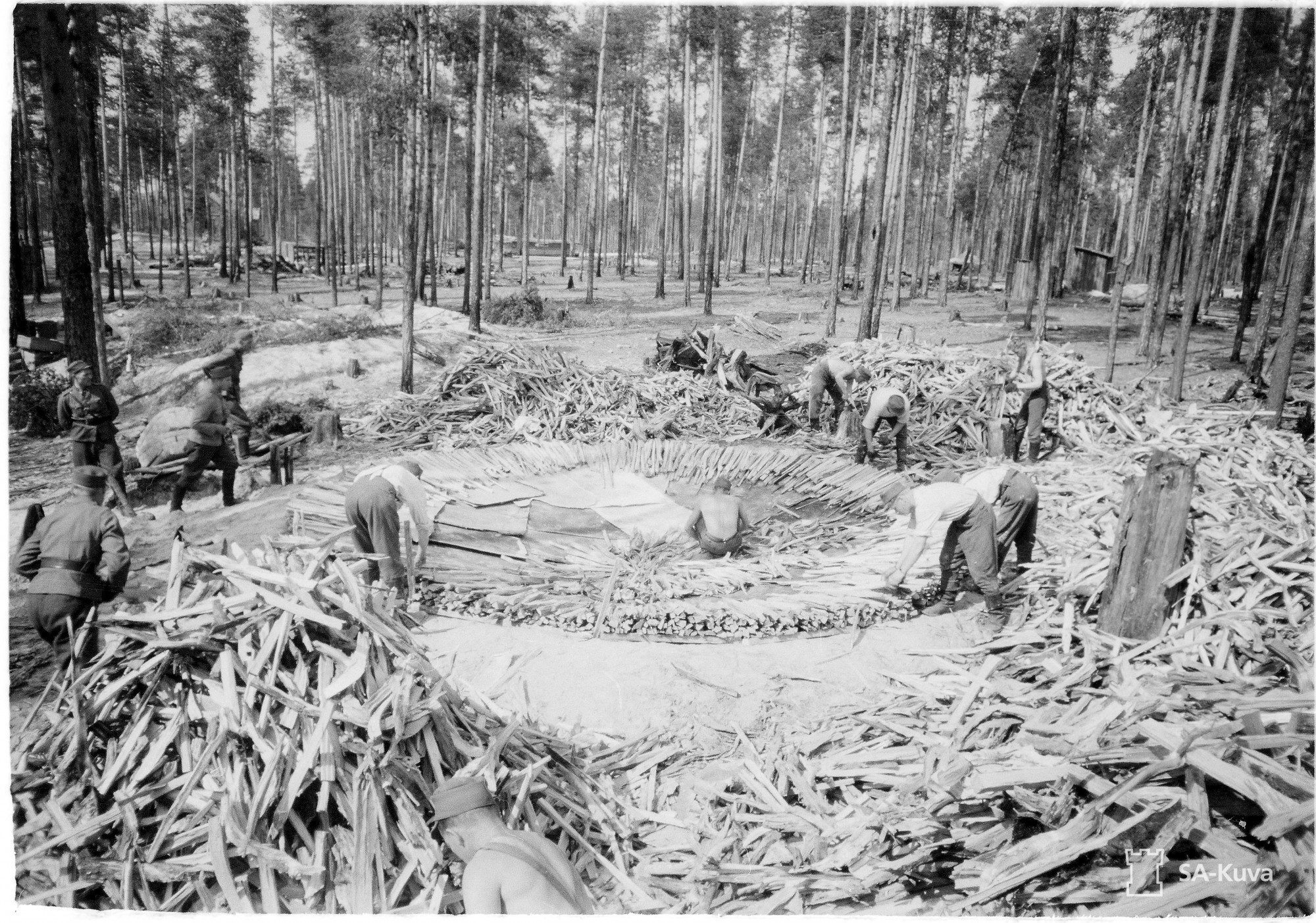

An often overlooked ‘carbon derivative’ in the expropriation of land in the Americas is terva (pine tar), which was used as a wood preservative. Finnish pine tar (often referred to as Stockholm tar) is described in many archival exchanges between colonial powers as being the best both in quality and fabrication method (Kent 1973, 80).

Finland has historically been one of the most important providers of both timber and tar for many of its European neighbours’ pillaging ventures abroad. The fluctuation of the black gold’s resale value is linked to both the creation of a bourgeoisie (in Oulu), and to great famines (Kainuu region). The increase of timber value, also afforded by the demand of trading companies and naval fleets, afforded the switch from an agricultural to a monetary economy. These reforms are dubbed the ‘liberalization of Finland’ in the 1860s, which also coincide with the creation of the Finnish markka, and the beginning of a widening gap between forest owners and landless peasants (Toivanen 2018). These reforms also precipitated the ‘hunger lands’. One of the main factors in the great famine of 1867 killing hundreds of thousands, was the inability to finance cereal import because of the decrease in the price of pine tar (Toivanen and Kröger 2018). Pine tar thus brought the beginning of speculation, riches as well as extreme poverty to the country.

Pine tar today in Finland epitomises the complexities challenging the co-existence and development of traditional practices alongside a bureaucratic apparatus that privileges the logic of accumulation. Under EU law, terva is categorised as a chemical which requires a production permit costing 200,000EUR (Braunschweiler n.d.). The EU chemical definition was devised according to industrial production methods and scale. Small artisanal terva producers have to merge or collectivise to survive. While this traditional knowledge is under constant threat of disappearance under the EU’s legal framework, in former tar production and distribution areas (such as Oulu and Kainuu), pine tar festivals have emerged as a hipster-esque nostalgia of Finland’s past, dehistoricising its relationship to death, famine and speculation.

Text excerpt from:

Gallardo, Francisco, and Audrey Samson. Carboniferous Capitalism. HIAP. https://www.

hiap.fi/carboniferous-capitalism1/. Published 2020. Accessed November 10, 2020.

…

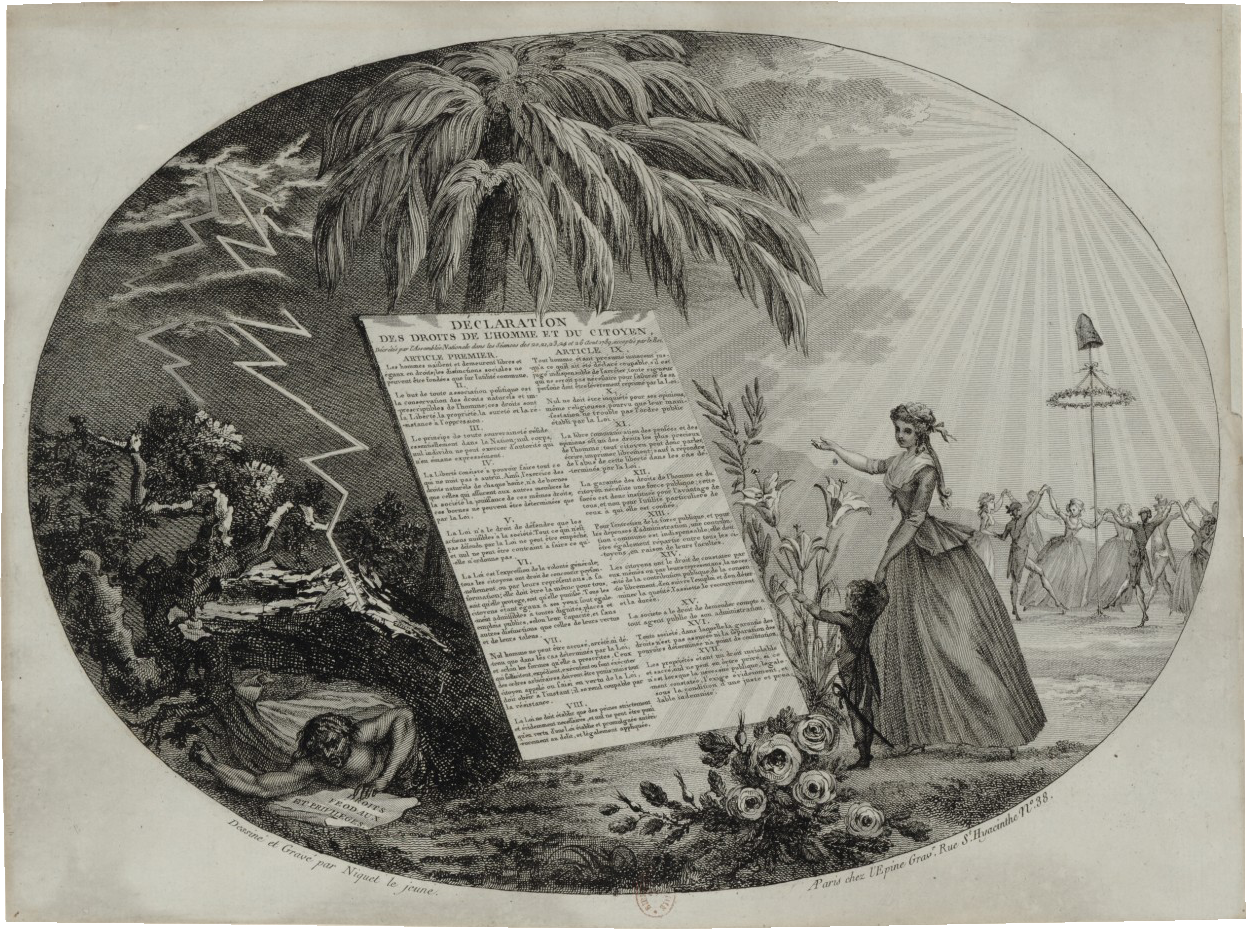

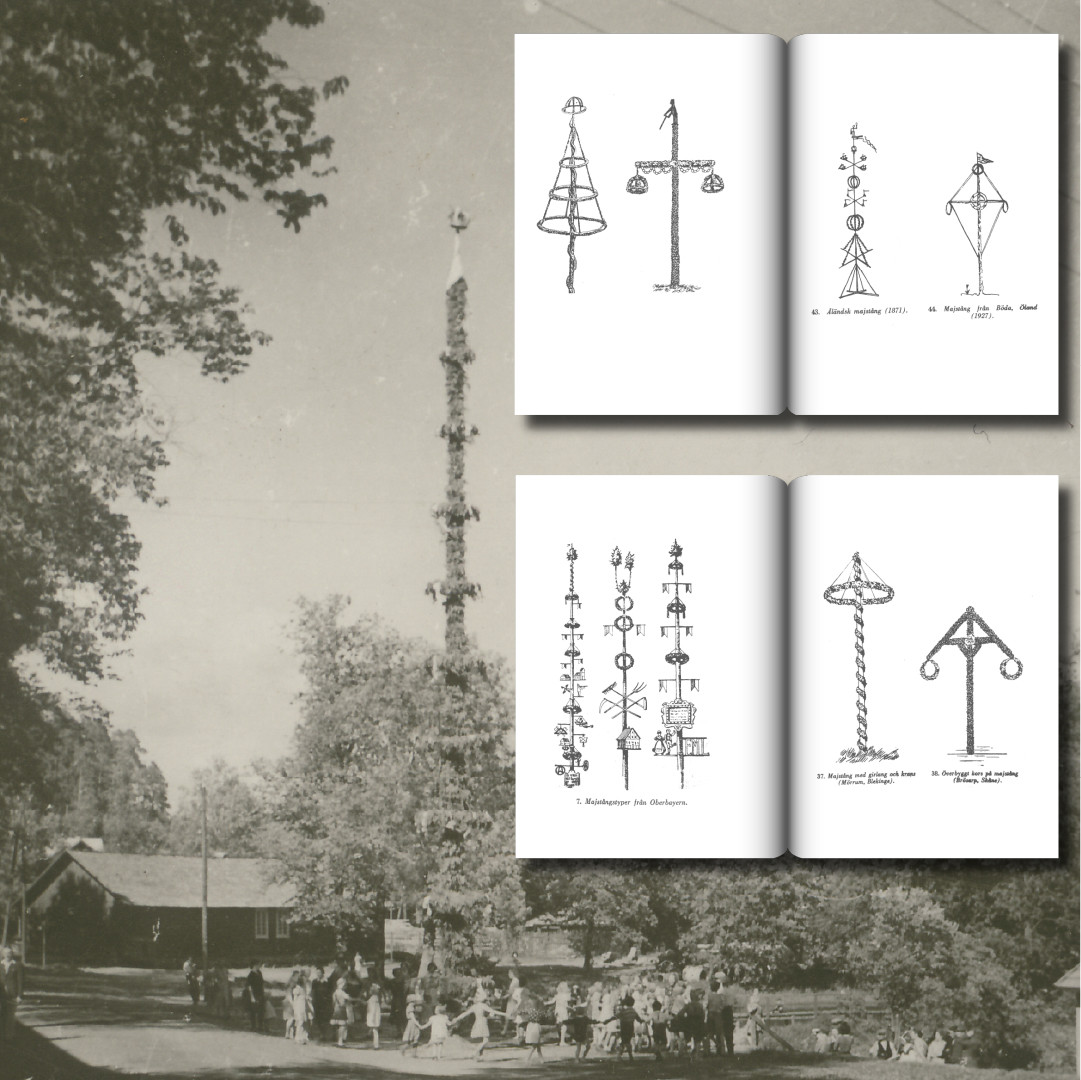

Maypole

Maypole

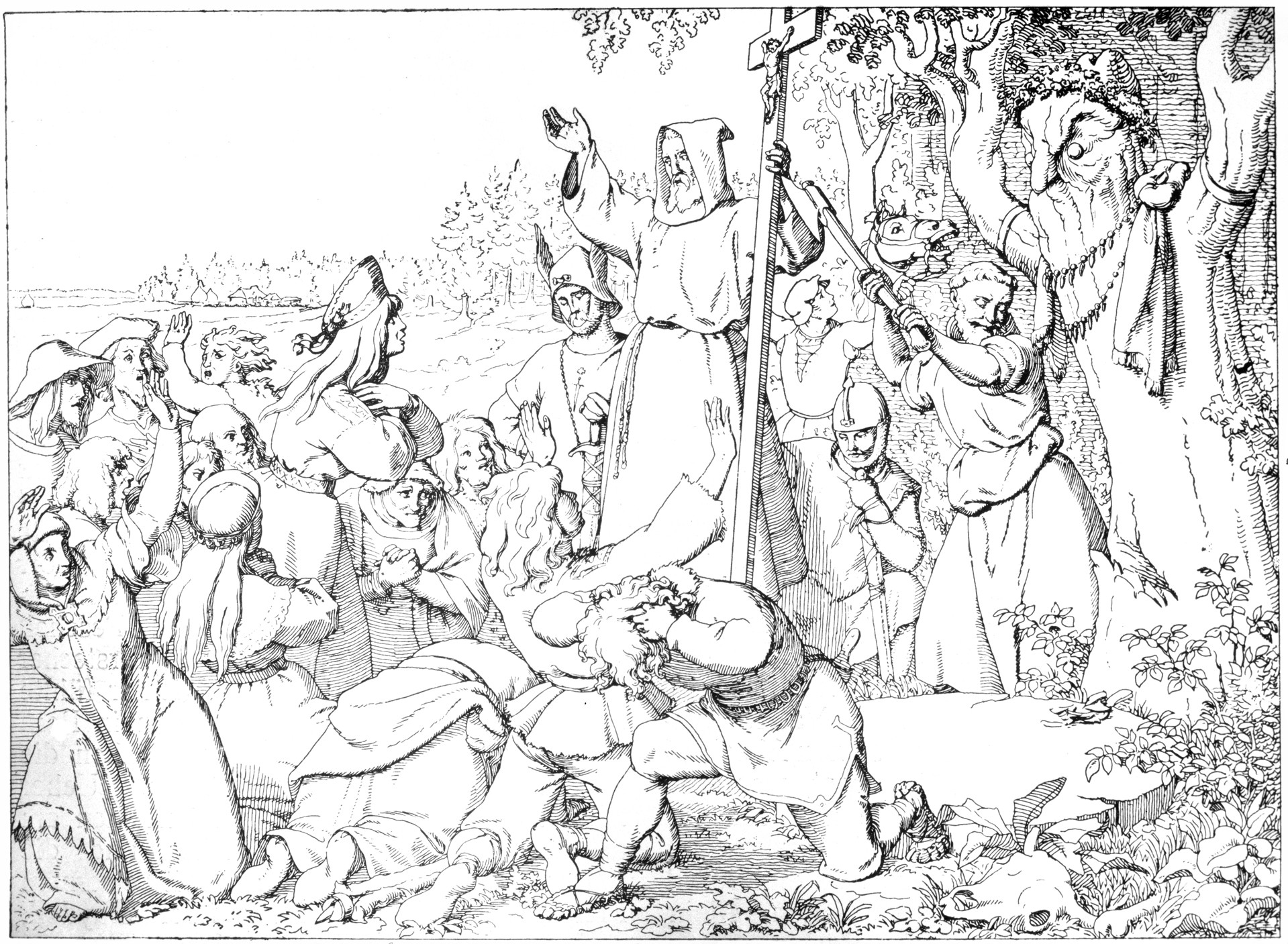

Birch and pine garlands decorated poles (often ship masts), which were erected in offering of good harvests, celebration of the beginning of the 'light days' (Celtic calendar), or as popular tribunals where governors, barons and kings were deposed and punished if ruled guilty. These May Poles were hoisted in fields and meadows known as the 'Ey-commons' or 'Fields of May'. Thus meadows operated as the highest court in popular law - now known for example in England as ‘commons law’.

…

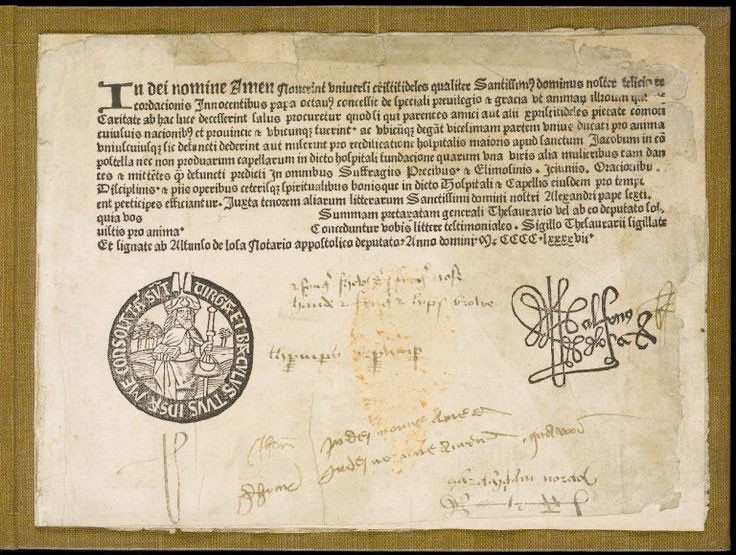

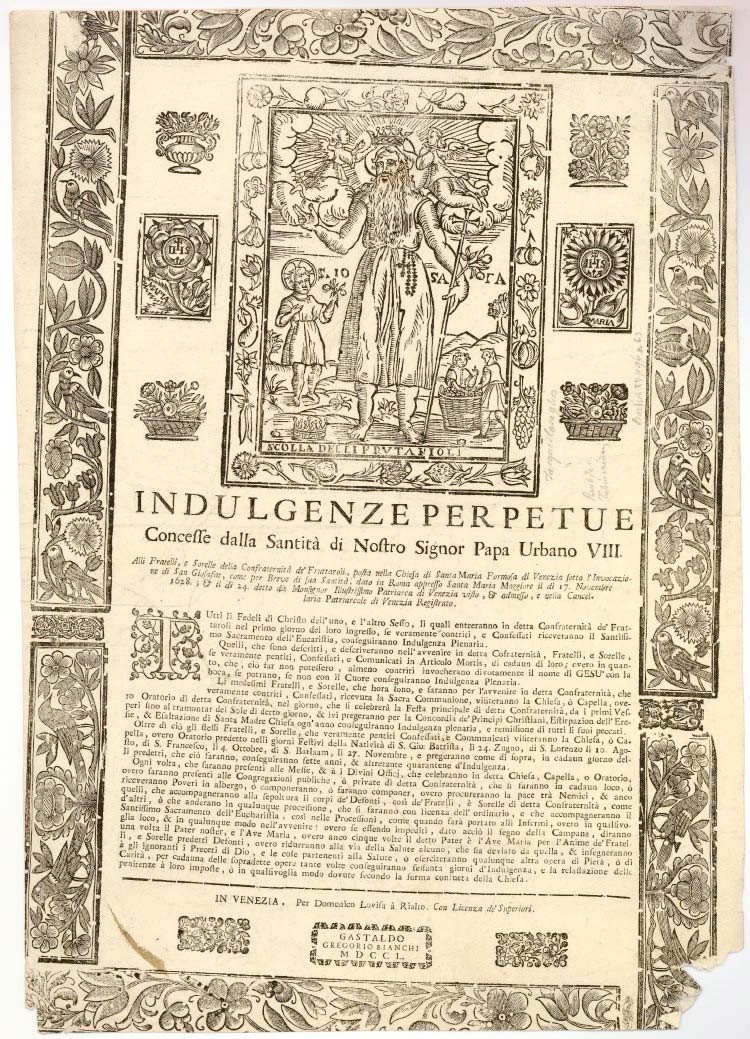

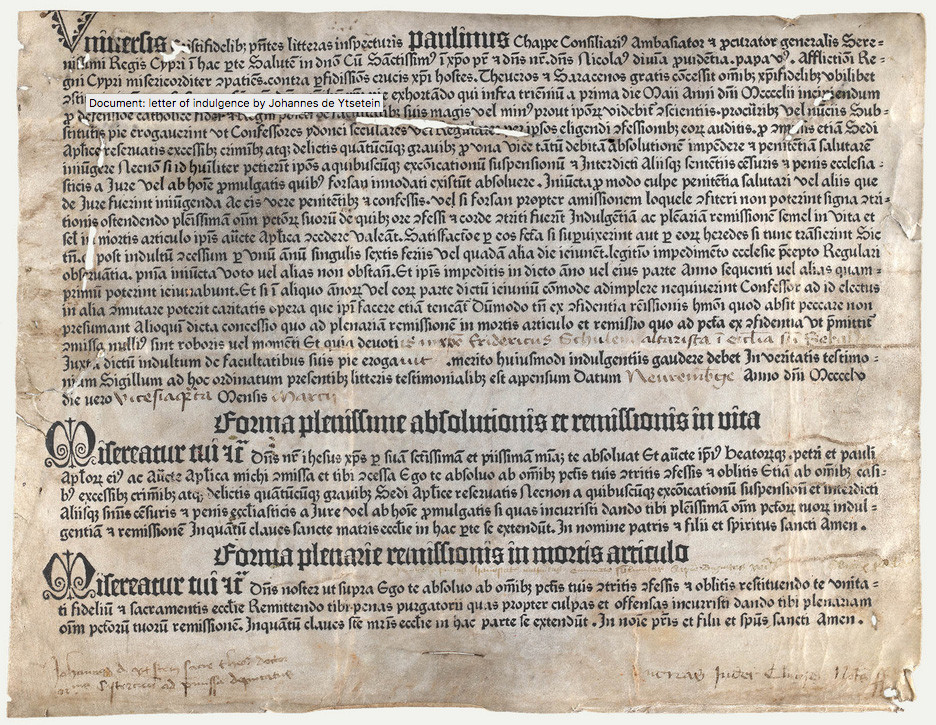

Indulgences

Indulgences

-Mantuan, Lib. 3.

The Vatican had the monopoly of three notable resources during the early modern period: salt, alum and indulgences. Indulgences approximately date back to the third century. At that time, rather than ‘indulgences,’ they were named by Latin terms such as remissio, absolutio, and relaxatio. The beginning of the abuses in indulgence sales started with practices of returning stolen goods. Architectural historian François Icher explains, “thieves and holders of stolen goods were promised absolution and forgiveness on condition that they give up all or part of the goods they held illegally not to the rightful owners, but to the Church.” Redemption was another predecessor of indulgences, given as a reward for charitable actions.

Indulgeo, "to be kind or tender" in latin, derives from Roman Law and biblical sources. Indulgences are a 'quid pro quo', which used in English to mean an exchange of goods or services, in which one transfer is contingent upon the other. It implies remitting the punishment of sin for a price. It does not buy forgiveness, in fact it only lessens the penance imposed. In other words, an indulgence is a remission before God of the temporal punishment for sins, the guilt of which has already been forgiven. The absolution is obtained by a member of the Christian faith under certain and definite conditions with the help of the Church. As the minister of redemption, the Church dispenses redemption from the spiritual “treasury”. The process is roughly analogous to a civil court proceeding in which a person who pleads guilty receives a sentence or penalty from a judge. Judges can suspend the sentence or order community service in lieu of prison time. Granting an indulgence is comparable to commuting a sentence (a commutation is a reduction in sentence, not a pardon).

The intended disposition of an indulgence followed this rationale: the Christian Church was endowed with a spiritual “treasury” of the piteous works bankrolled by merits attributed to Holy figures such as Christ and saints. The Church acted as a bank, storing and distributing at discretion those 'merits'. An indulgence placed at the penitent's disposal from the aforementioned treasury designated retribution for their sinful act. They are often described similar to a “Utopian commonwealth where all the surplus wealth of the successful citizens should be set apart for the poor and needy, and portioned out to them according to their necessities”. In effect, a customary mode of thinking about this was that of 'governing by debt'. Believers would thus be bailed-out through retributory work such as making a pilgrimage, Crusade enrolling, almsgiving, or by performing special prayers. Since these alms provided much of the revenue needed for crusades, and later the costs to build New St. Peter’s, the exchange of indulgences for alms, later deemed “sales,” rose in the years prior to the Reformation. 'Salesmen' refers to those travelling business-priest men sermoning about the urgencies for indulgences. Again Icher explains that “while the building sites depended unquestionably on the rhythm of the seasons, they operated primarily according to the rhythm of money”.

Through the massive emission of indulgences, the Christian Caesar, a.k.a Pope, became the most formidable force in Europe – a prominent power player and art patron. Lorenzo Pucci stated that the mass runs of indulgences rolled off ecclesiastical printing presses. We could think of the Pope as the one-man Tate or MoMA, underwriting the best contemporary artists, using charm, threats, bribes, and flattery to commission the masterpieces of western civilisation. For the Saint Peter cathedral, Agostino Chigi proposed a financial plan: the granting of indulgences. He advised to set up a separate building fund for the basilica and grant an indulgence to anyone who made an annual contribution to it. This idea is similar to pledge drives today, receiving a reduced purgatory sentence. The term "pledge" originates from the promise that a contributor makes to send in funding at regular intervals for a certain amount of time. Prior to that indulgences were an accepted way to raise money for capital projects and charitable causes. The initial methods to finance Church construction was to cut costs, and thereafter to raise money through indulgences.

Both of the churches in Wittenberg were granted indulgences and a special indulgence was issued for the reliquary-museum, which the elector Frederick had collected. An indulgence of 100 days was attached to each of the 5,005 specimens and another 100 to each of the 8 passages between the cases that held them. With the 8,133 relics at Halle and the 42 entire bodies, millions and billions of days of indulgence were associated, a sort of anticipation of the geologic periods of modern demand. To be more accurate, these relics created pardons covering 39,245,120 years and 220 days, and the still further period of 6,540,000 quarantines, each of 40 days.

The main intent of Julius II’s bull 'Liquet omnibus', issued in 1510, was to generate great sums of money to build New St. Peter’s and draw the faithful to Rome. This bull set clear financial conditions to all Christians hoping to gain the indulgence. They were to “deposit in the chest the price determined by the commissioner or his delegates,” and the prices of indulgences were set according to their ability to pay. For instance, Archbishop Albert of Mainz and Magdeburg set the following standards: kings, princes and great prelates paid twenty-five Rhenish gold gulden for an indulgence; abbots, cathedral dignitaries and nobles paid ten gulden; lesser prelates, nobles, and traders with an income over five hundred gulden paid six gulden, burghers and merchants whose revenues were about two hundred gulden paid three gulden; and below these the amount paid was a half to one gulden. If one was too poor to pay anything, they were given other works, initially fasting or prayers, then indentured labour. It might be relevant to recall that labour constituted a great expense, approximately reaching forty percent of the construction budget in large architectural works.

Geologic time

In Rome, the residence of the supreme pontiffs, as we might well have expected, the offer of indulgences was the most copious. According to the Nürnberger relic-collector, Nicolas Muffel, every time the skulls of the Apostles were shown, or the handkerchief of St. Veronica, the Romans who were present received a pardon of 7,000 days, other Italians 10,000 and foreigners 14,000. In fact, the grace of the ecclesiastical authorities was practically boundless. Not only did the living seek indulgences, but even the dying stipulated in their wills that a representative should go to Assisi or Rome or other places to secure for their souls the benefit of the indulgences offered there.

Prayers also had remarkable offers of grace attached to them. According to the penitential book, The Soul’s Joy, the worshipper offering its prayers to Mary received 11,000 years indulgence and some prayers, if offered, freed 15 souls from purgatory and as many earthly sinners from their sins. It professed to give one of Alexander Vl.’s decrees, according to which prayer made three times to St. Anna secured 1,000 years indulgence for mortal sins and 20,000 for venial. The Soul’s Garden claimed that one of Julius II.’s indulgences granted 80,000 years to those who would pray the book’s prayer to the Virgin. No wonder Siebert, a Roman Catholic writer, is forced to say that "the whole atmosphere of the later Middle Ages was soaked with the indulgence-passion”.

Indulgences prevail today, they are namely included in the 1983 Code of Canon Law. Also, in 2013, Pope Francis issued indulgences via his Twitter account to those who followed his Twitter-feed during the World Youth Day event in Rio de Janeiro!

Source: Zutphen, Regionaal Archief, inv. 4.

↓

Practice

…

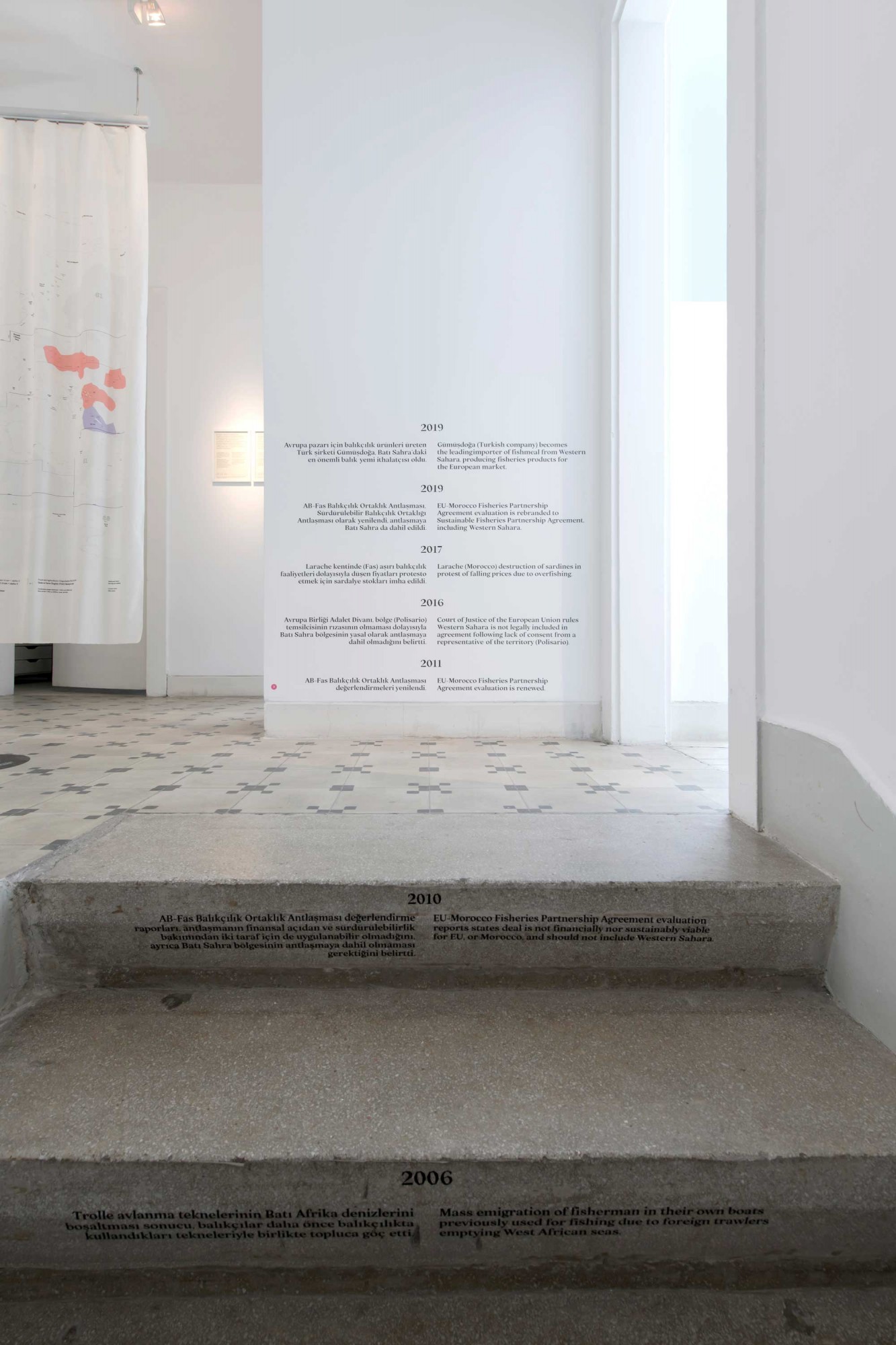

EU Policy Watch Tower

EU Policy Watch Tower

…

Unclaimed Latifundium

Unclaimed Latifundium

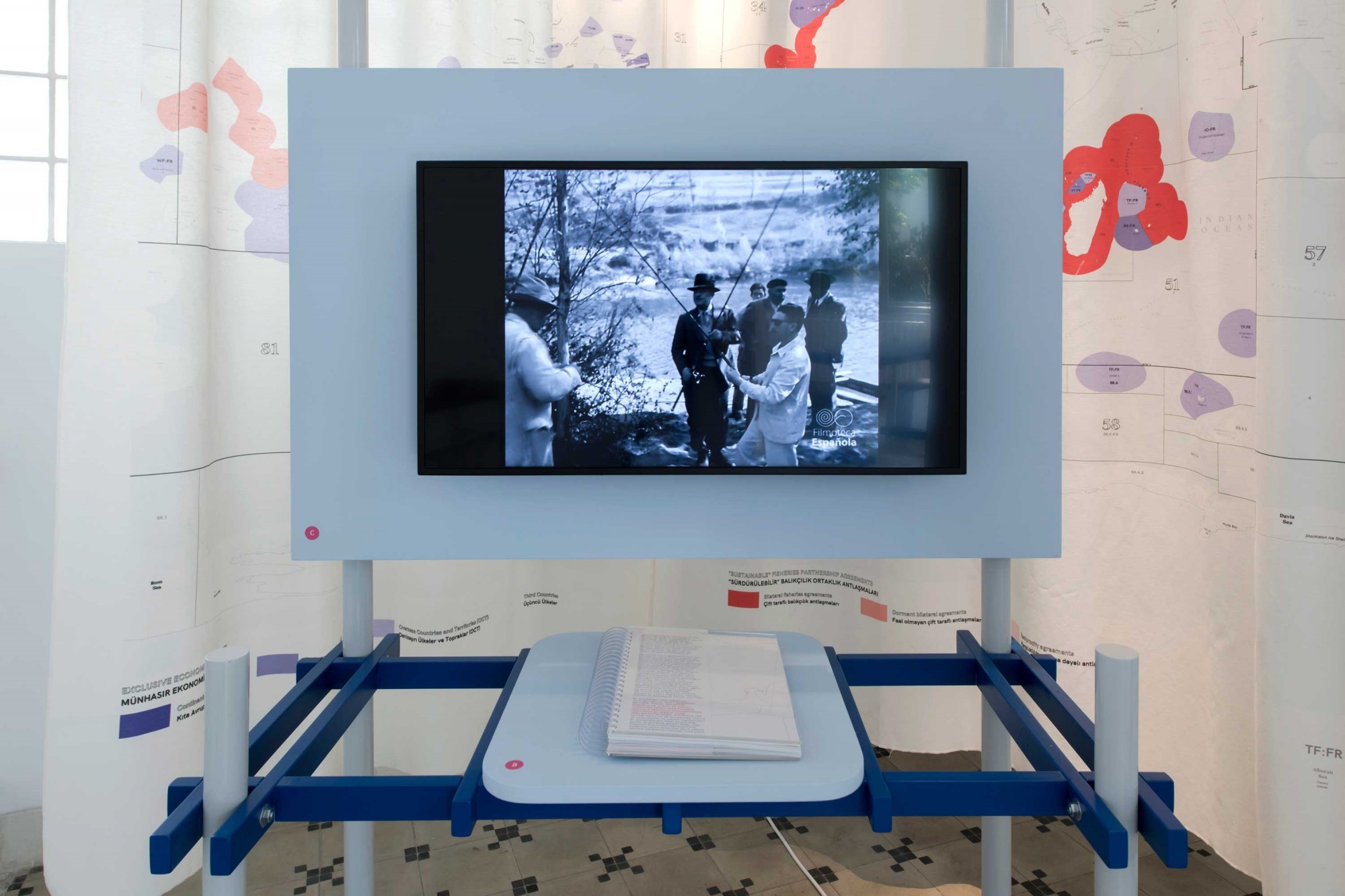

Unclaimed latifundium: Eat more, fish further! Is a video-piece which collates several excerpts from NO-DO newsreels related to Spanish fishing and fisheries propaganda under Franco's regime. His agenda was partly disseminated in cinemas through programmes called ‘NO-DO’, an acronym for 'Noticiarios y Documentales' (news and documentaries). NO-DOs were screened prior to films, usually lasting 30 minutes. These cinematographic preambles slowly constructed the myth of Francoist modernity, the latter including the aggressive development of industrial fisheries supported by the nostalgic backdrop of artisanal river fishing.

'Unclaimed Latifundium' was part of Partnerships, and produced as part of the 5th Istanbul Design Biennial — Empathy Revisited: designs for more than one, organised by the Istanbul Foundation for Culture and Arts, and curated by: Mariana Pestana, Sumitra Upham and Billie Muraben.

…

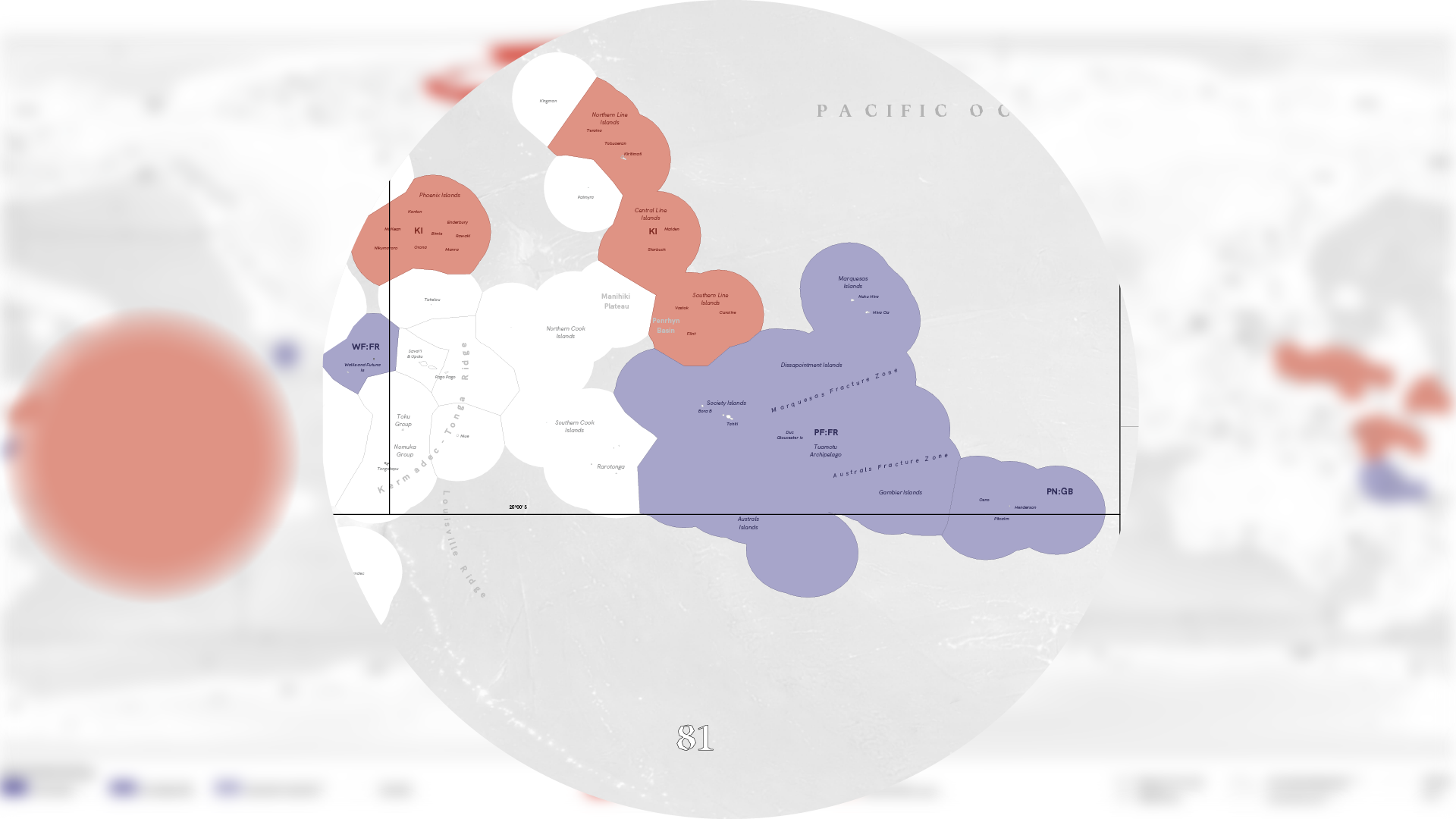

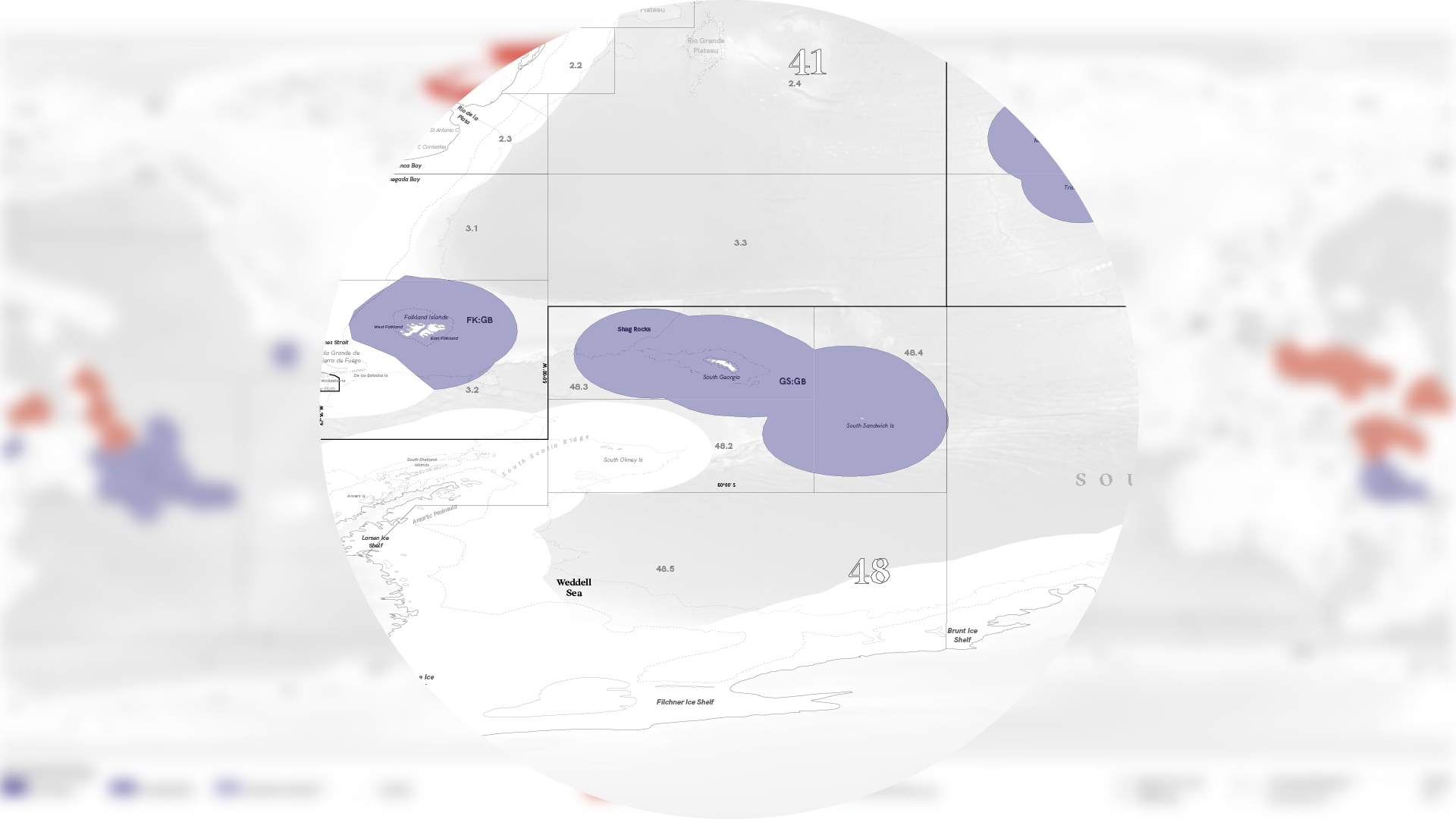

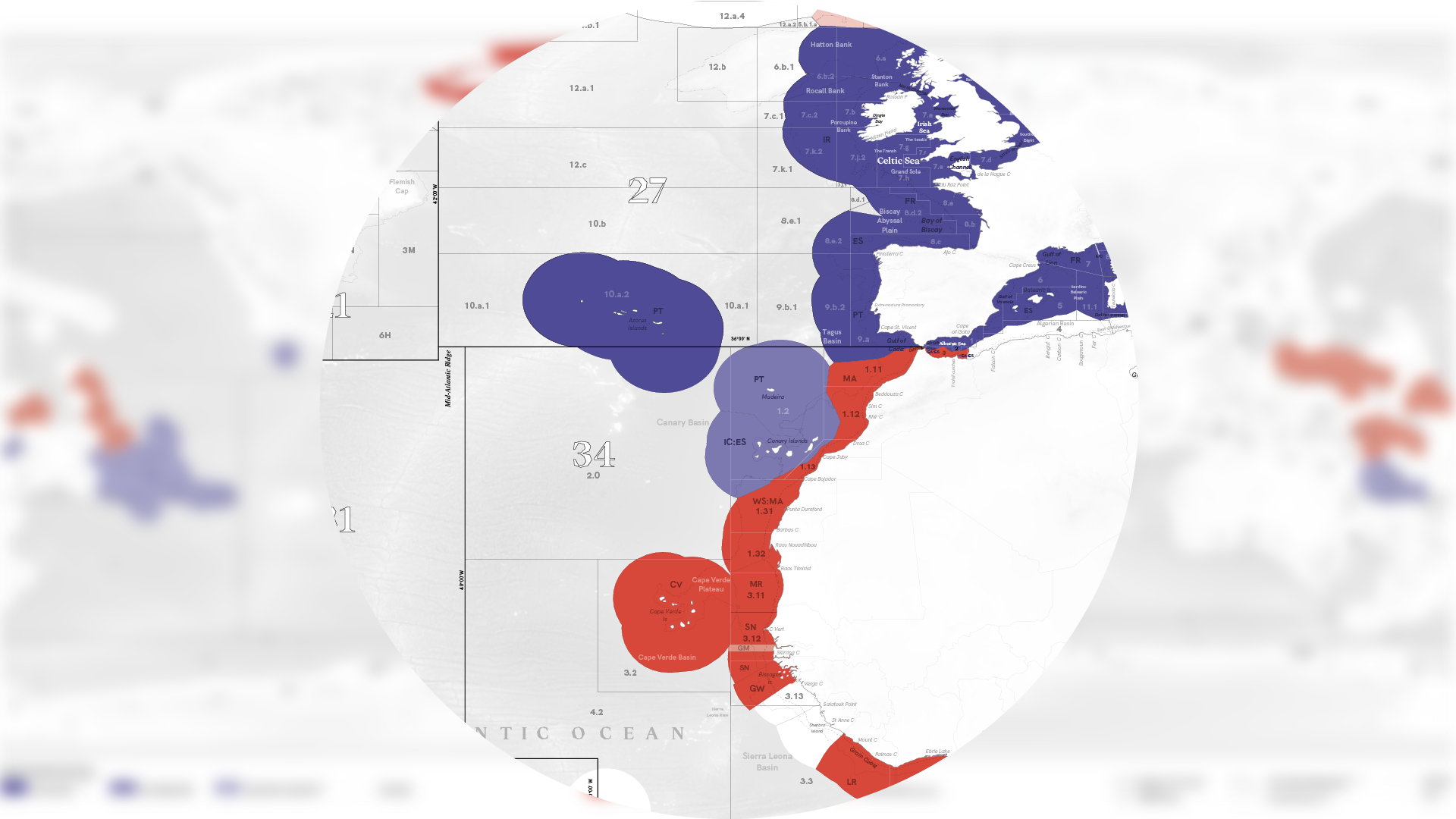

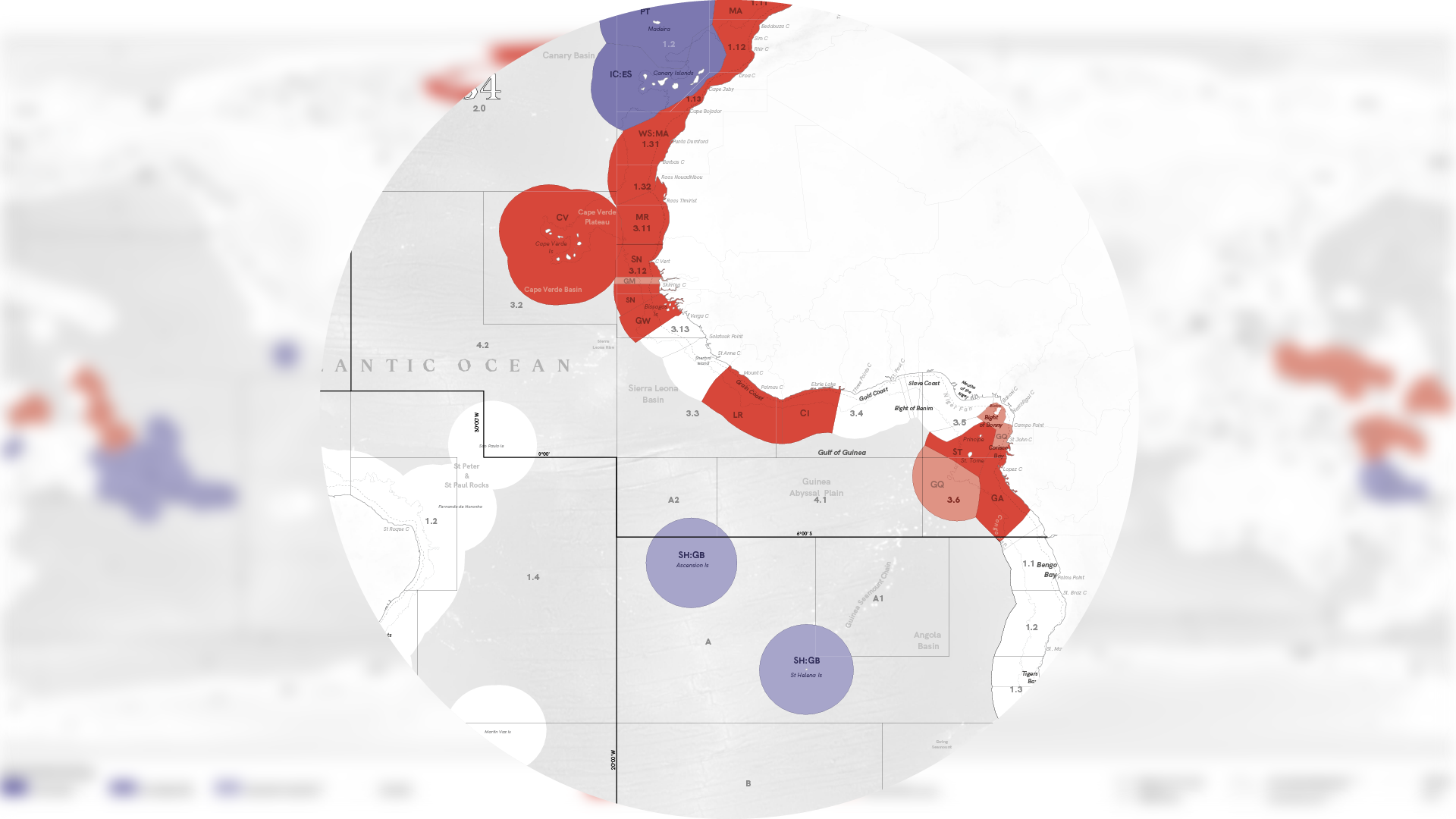

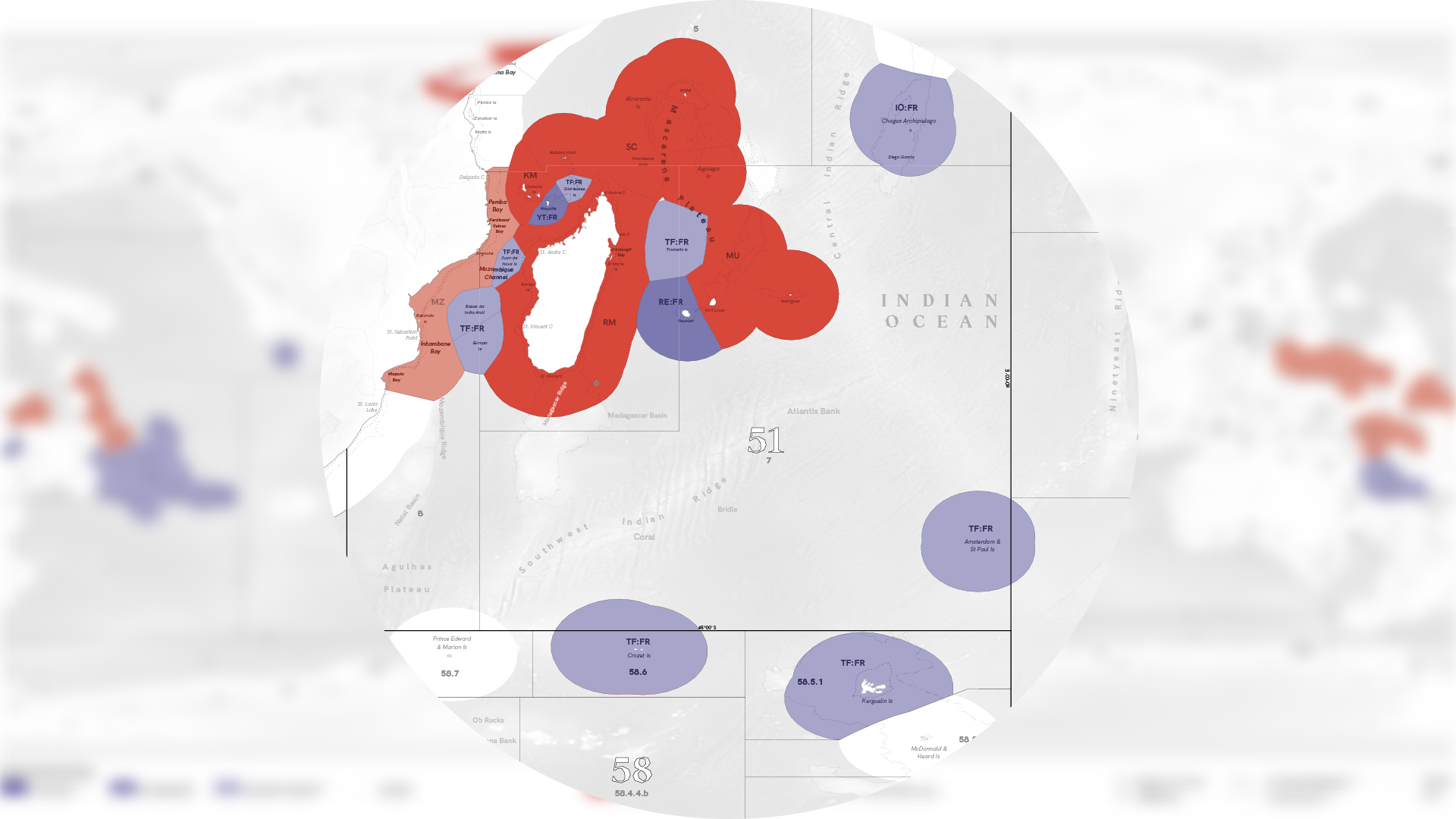

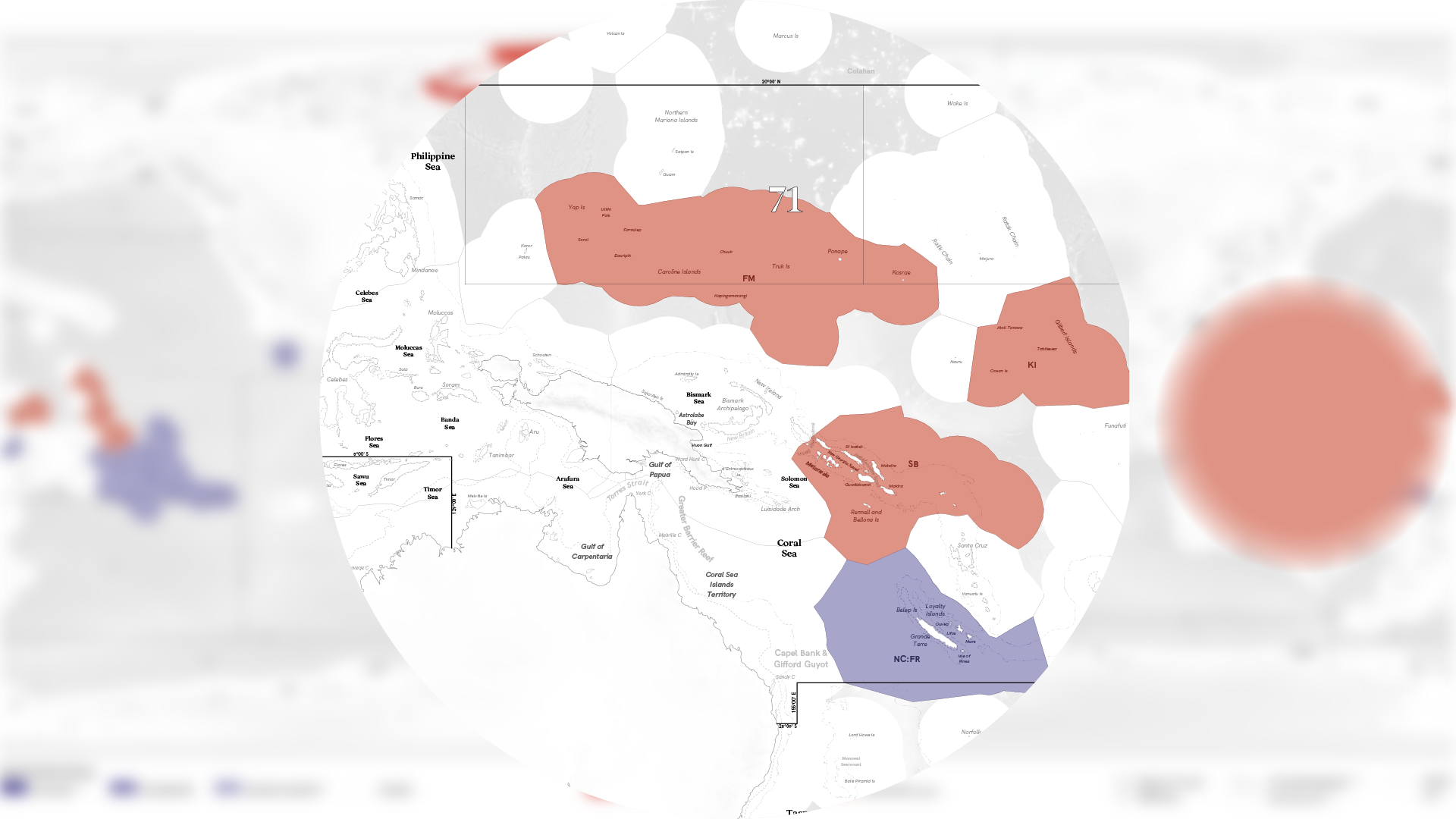

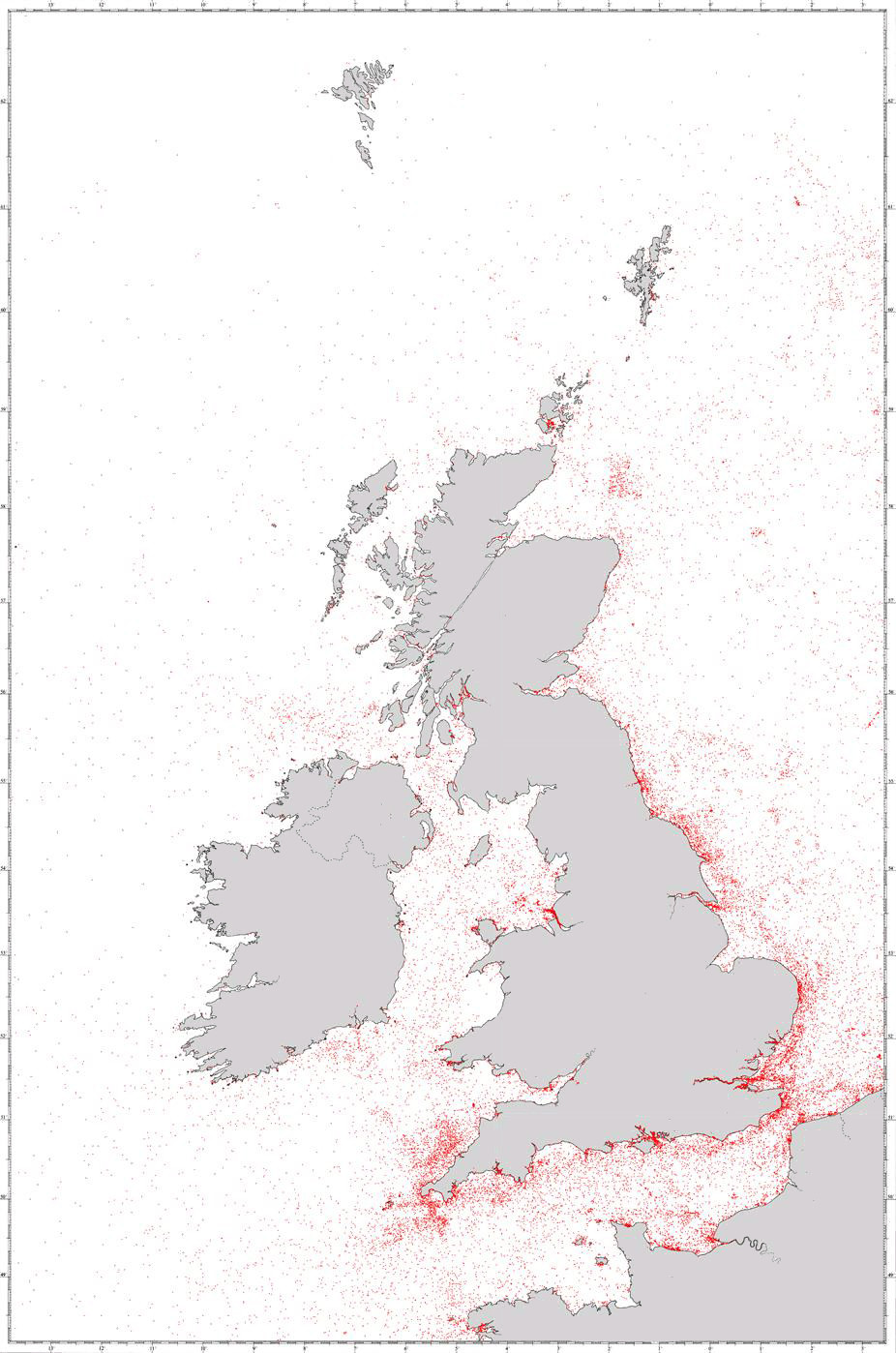

To Reap without Sowing Map

To Reap without Sowing Map

…

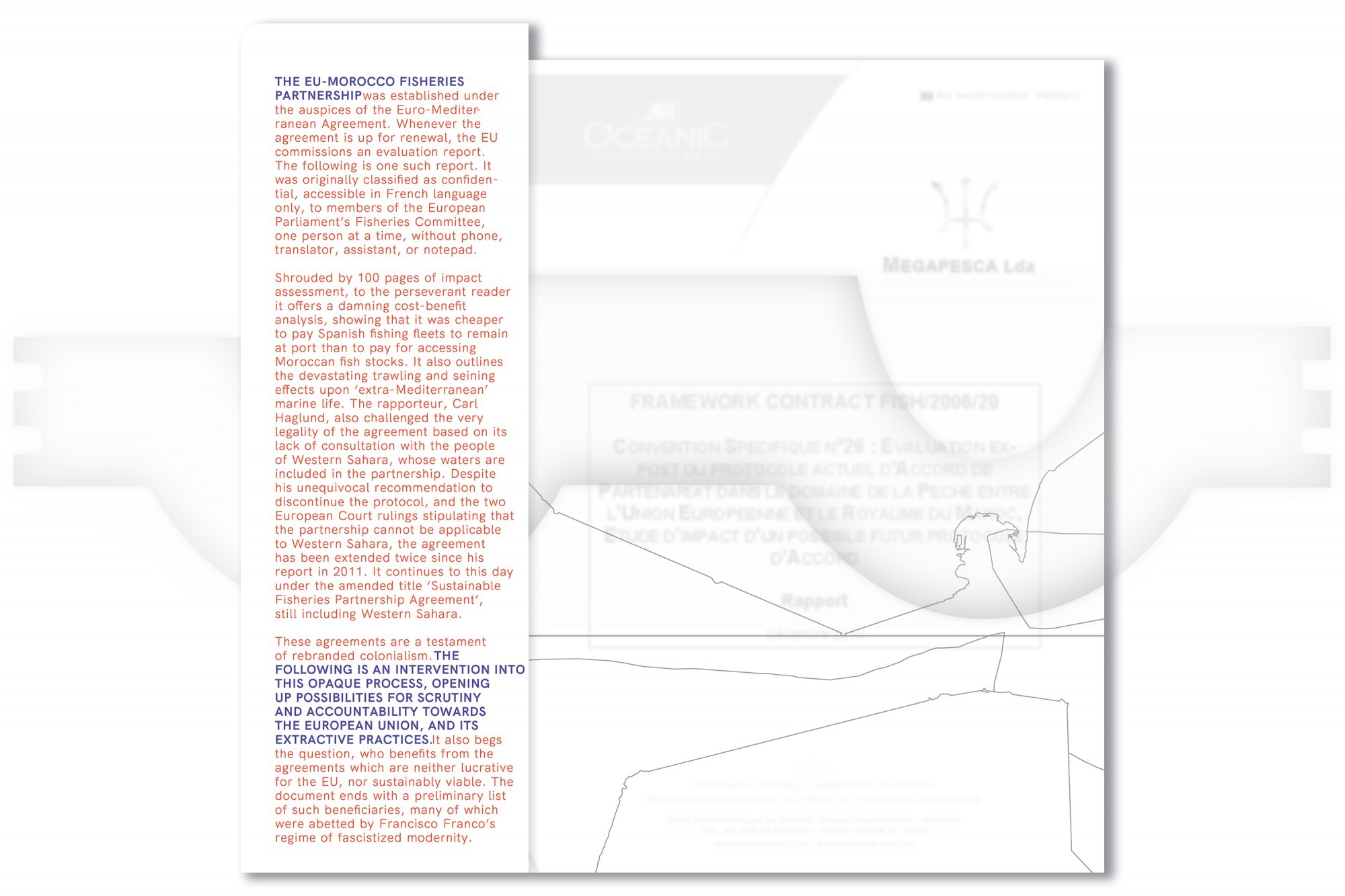

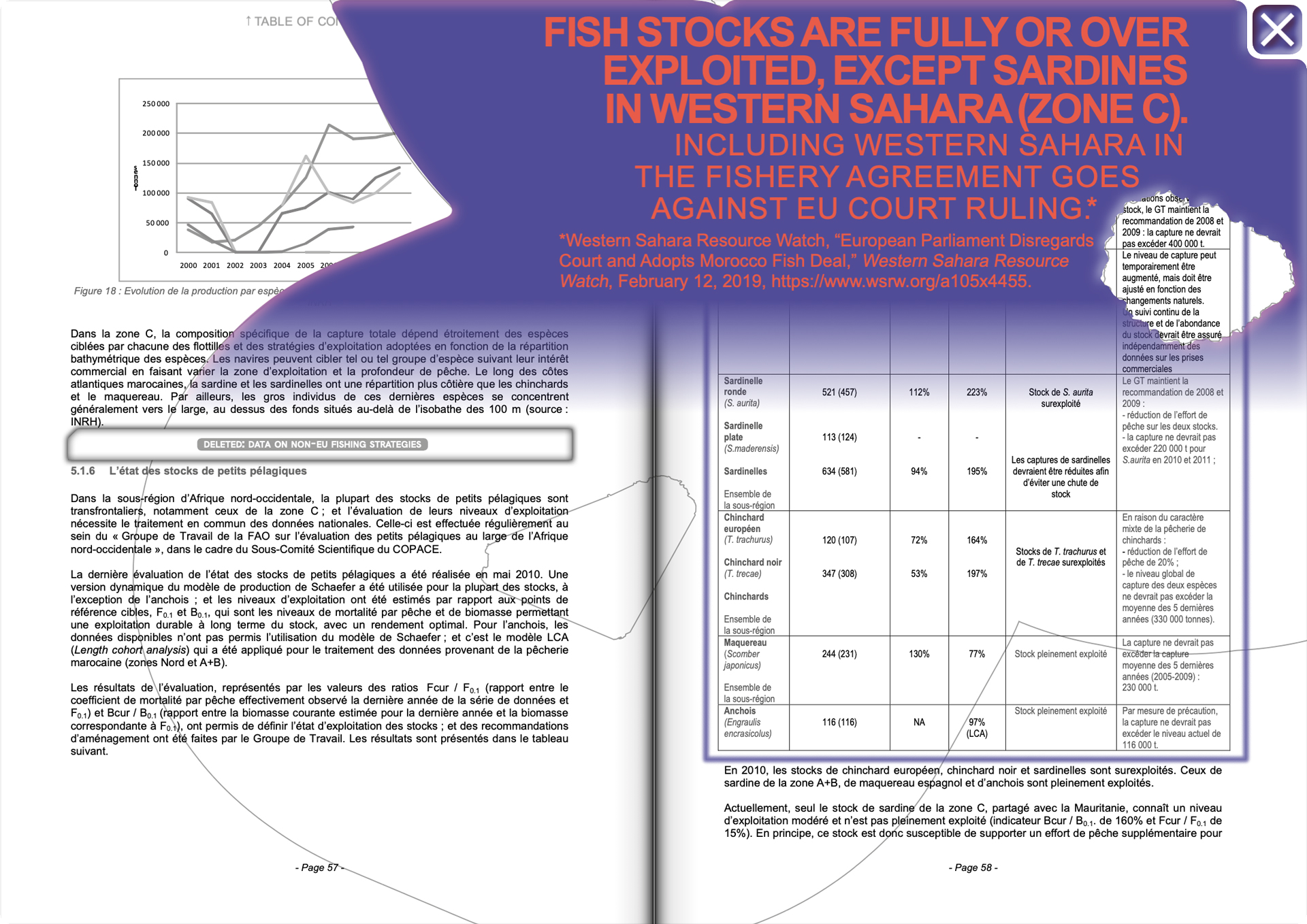

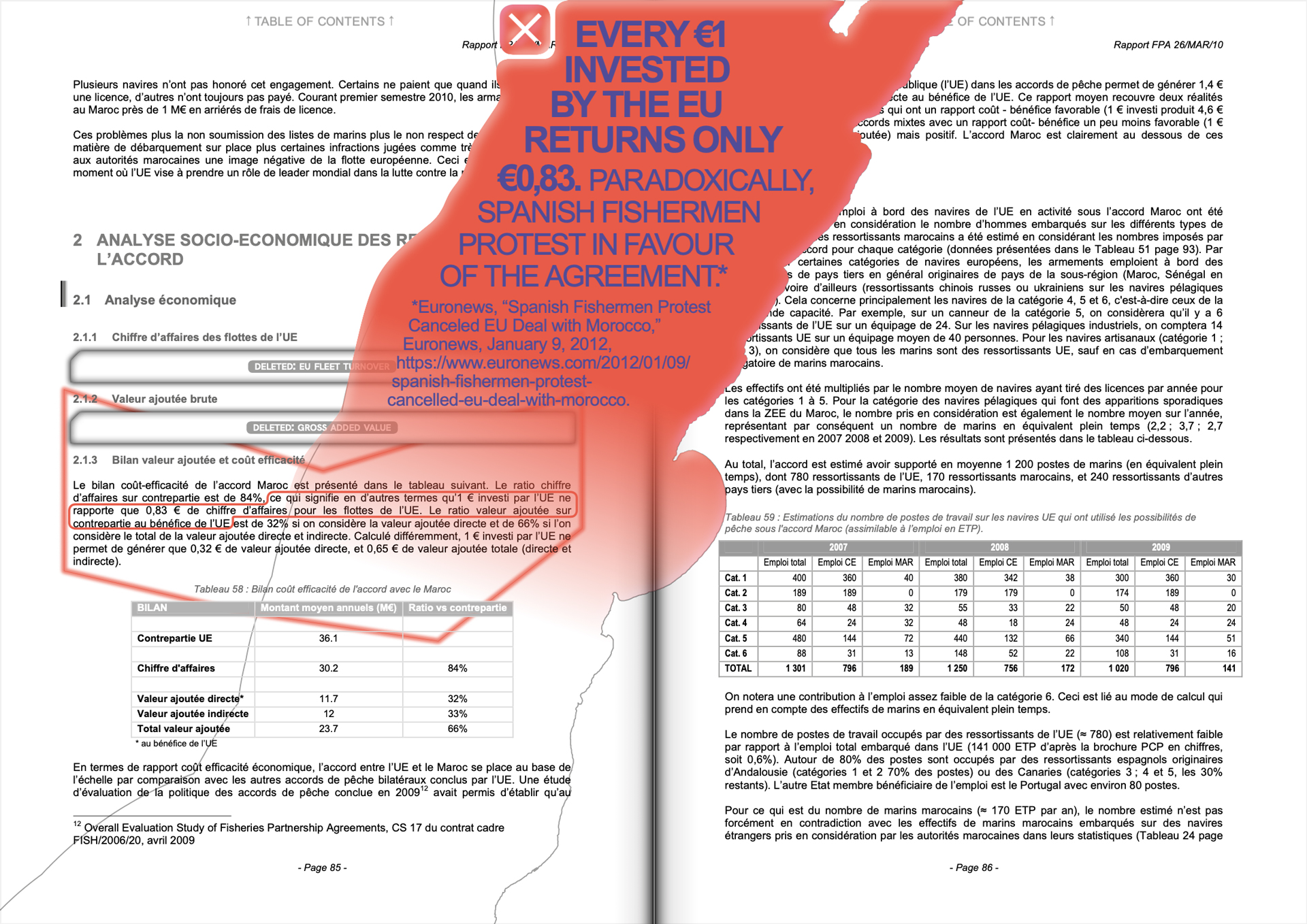

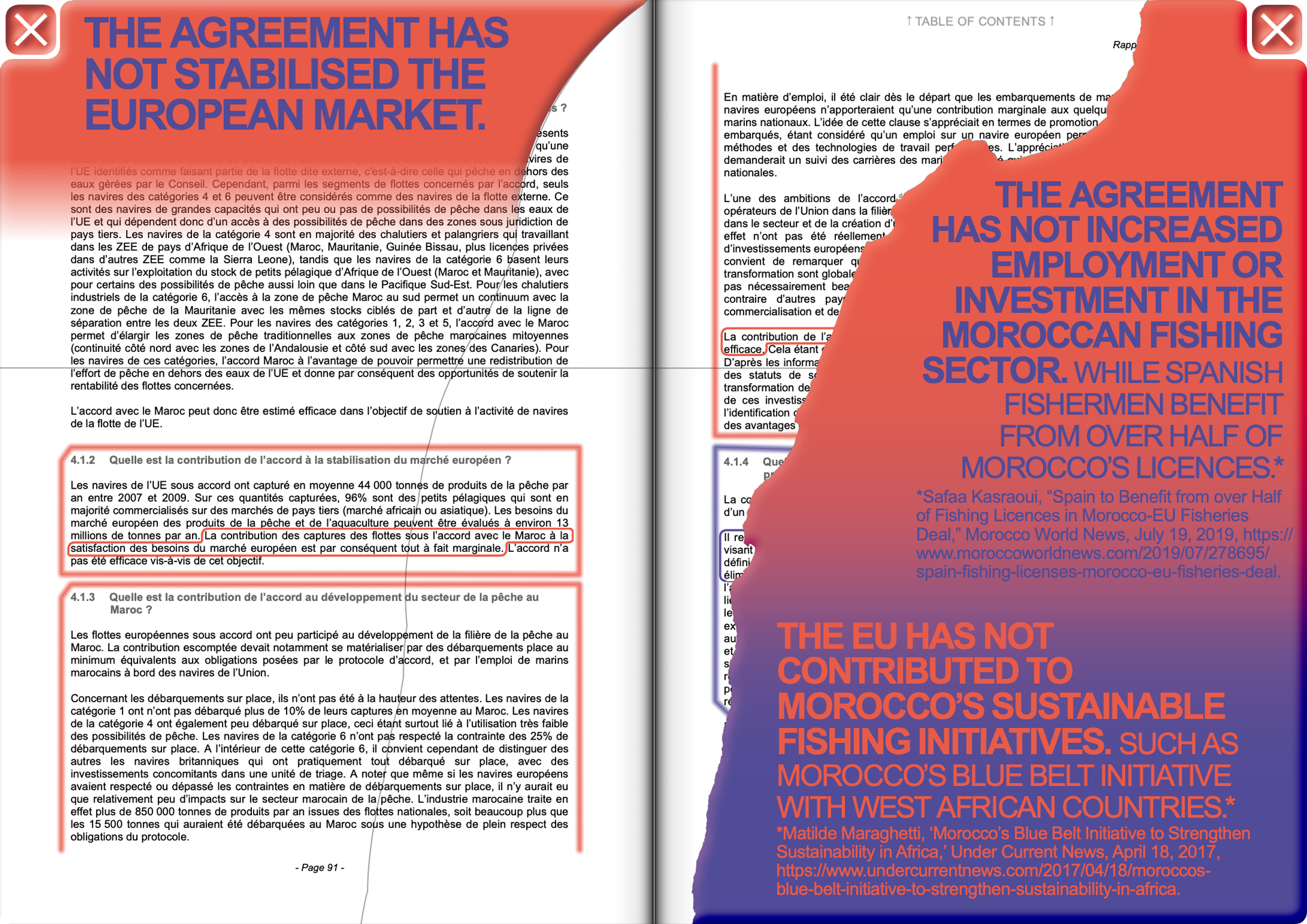

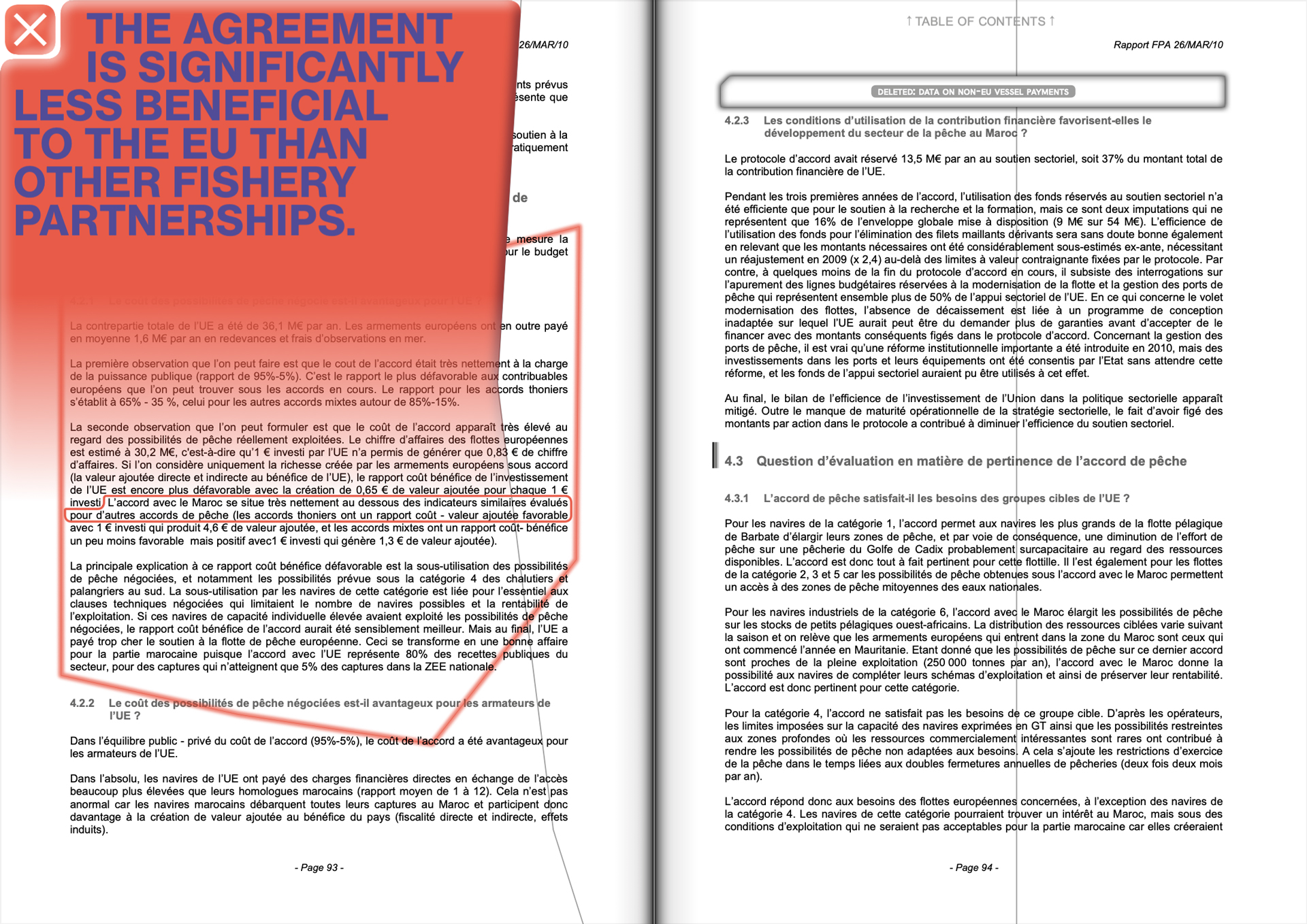

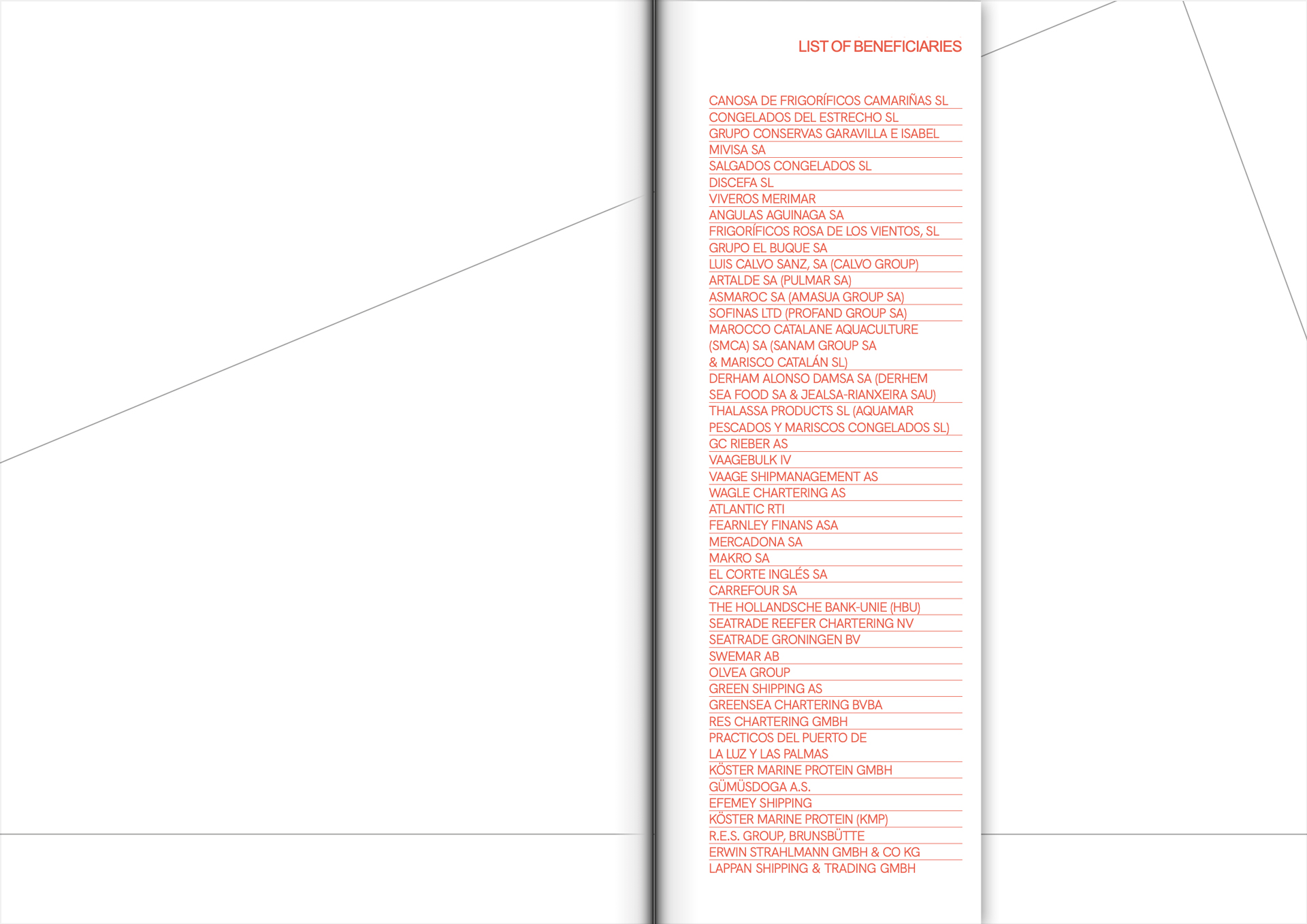

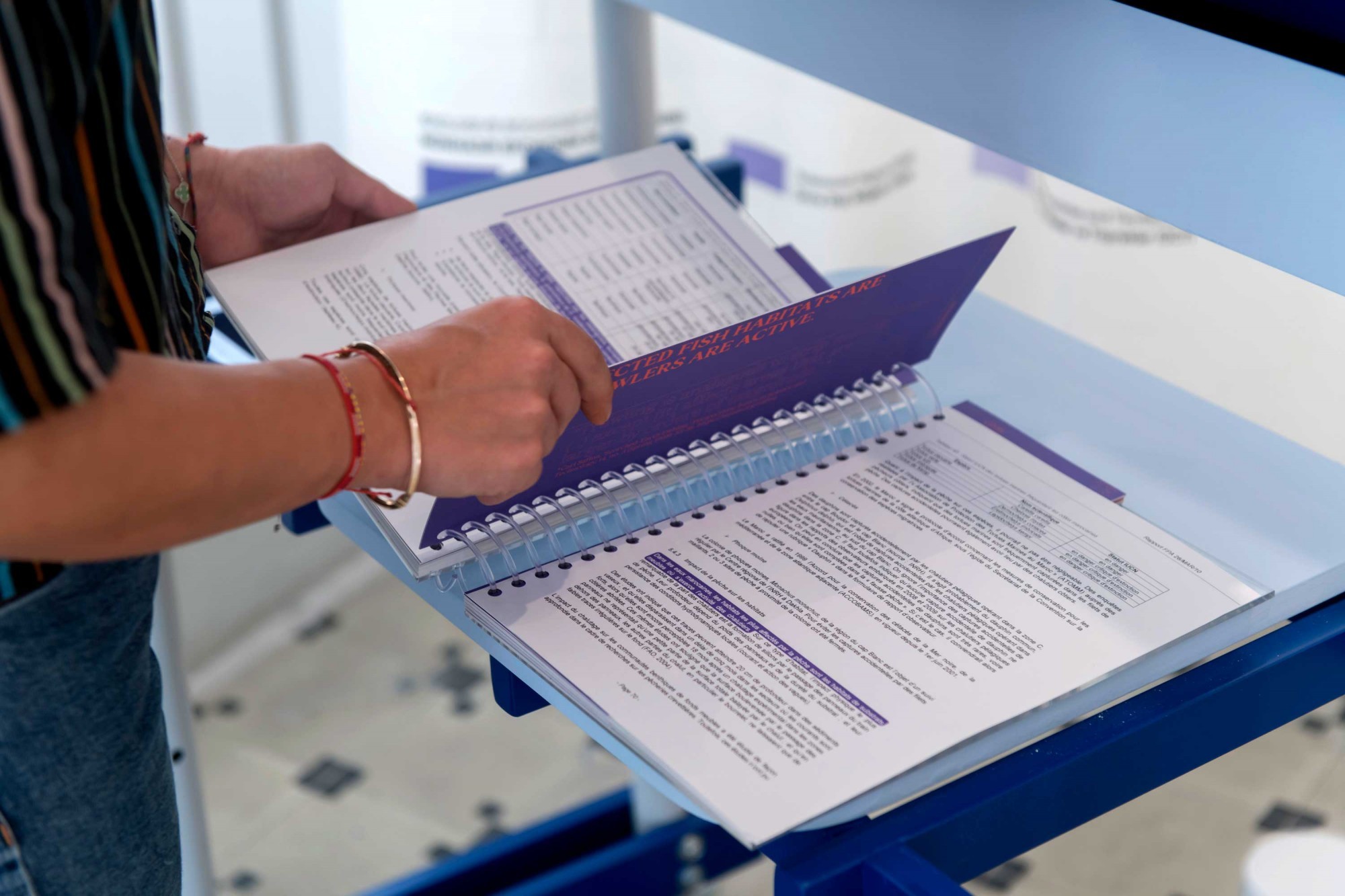

Ex-Post Re-evaluation Report

Ex-Post Re-evaluation Report

The controversial evaluation report of the EU-Morocco Fisheries Partnership Agreement (FPA) was also classified. Following the protocol of classified documents, the report was made available in a small room, adorned with a lightbulb, a chair, and a table. It was accessible only to members of the European Parliament’s Fisheries Committee, one person at a time, without phone, translator, assistant, or notepad. The document available for consultation, in French language only, offered a cost-benefit analysis, which showed that it was cheaper to pay Spanish fishing fleets to remain at port than to pay for accessing Moroccan fish stocks. It also outlined the devastating trawling and seining effects upon ‘extra-Mediterranean’ marine life.

The rapporteur, Carl Haglund, states in his draft recommendation to the European Council’s Fisheries Committee that the “economical, ecological, environmental and procedural problems with the Agreement are so grave that they outweigh the possible counterargument for giving consent to the extension of the Protocol”. He also challenged the very legality of the agreement based on its lack of consultation with the people of Western Sahara whose waters are included in the partnership. Despite his unequivocal recommendation to discontinue the protocol, and the two European Court of Justice rulings stipulating that the FPA is not applicable to Western Sahara, the agreement has been extended twice since his report in 2011 and continues to this day under the amended title ‘Sustainable Fisheries Partnership Agreement’, still including Western Sahara. According to Ignacio Cembrero, former journalist at El País covering the Maghreb, the “European Commission discovered a means by which European ships were able to continue to fish in Saharan water - making 91% of catches - all whilst respecting, according to them, the spirit of the Court’s rulings”.

This revised document is an intervention into opaque EU processes, opening up possibilities for scrutiny and accountability towards the European Union and its extractive practices. It also begs the question, who benefits from the agreements which are neither lucrative for the EU, nor sustainably viable?

…

Playa Taurito

Playa Taurito

…

Playa Mogan

Playa Mogan

…

EURion

EURion

…

Jable Pardo Tours

Jable Pardo Tours

jablepardo.tours

…

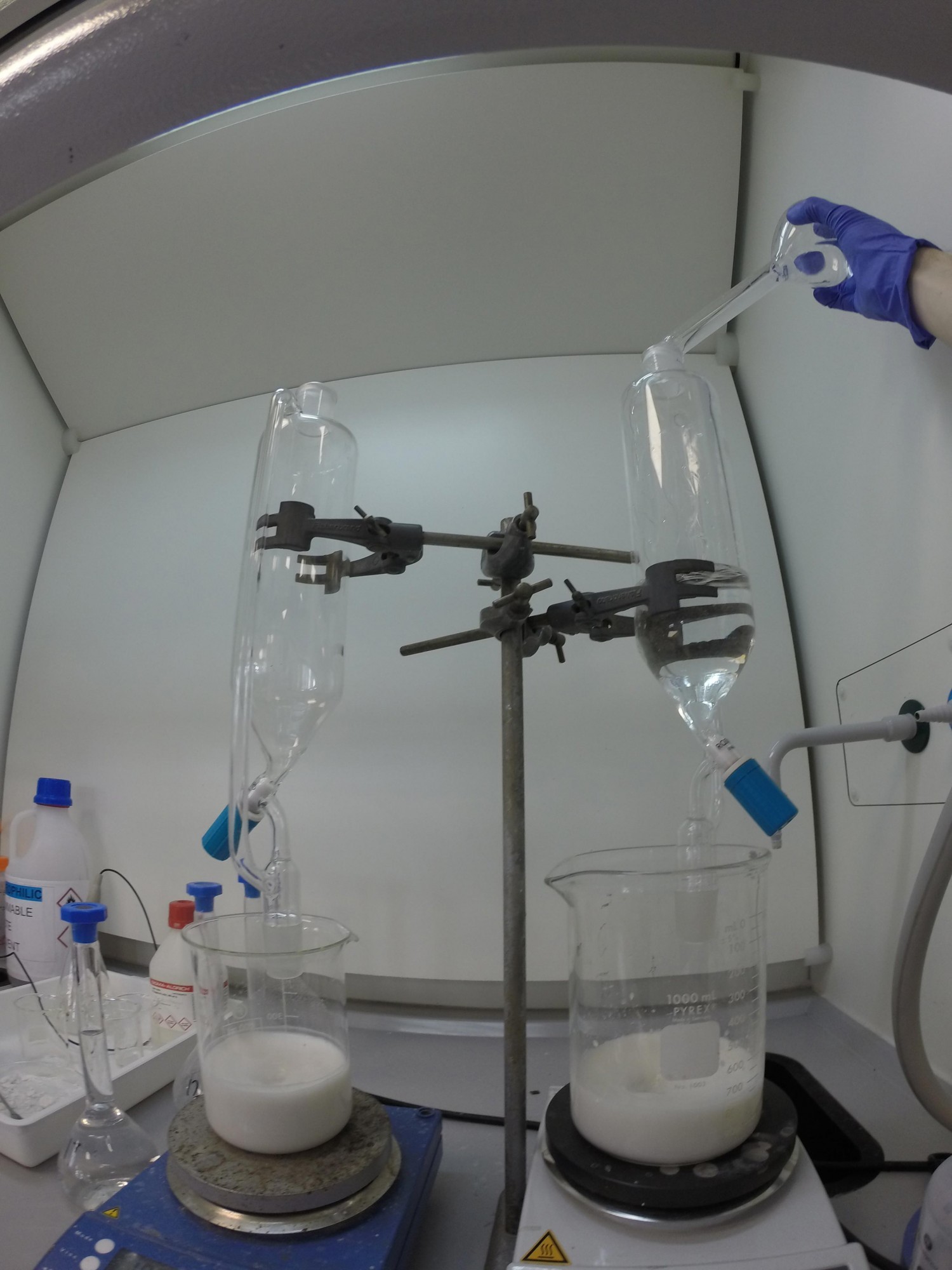

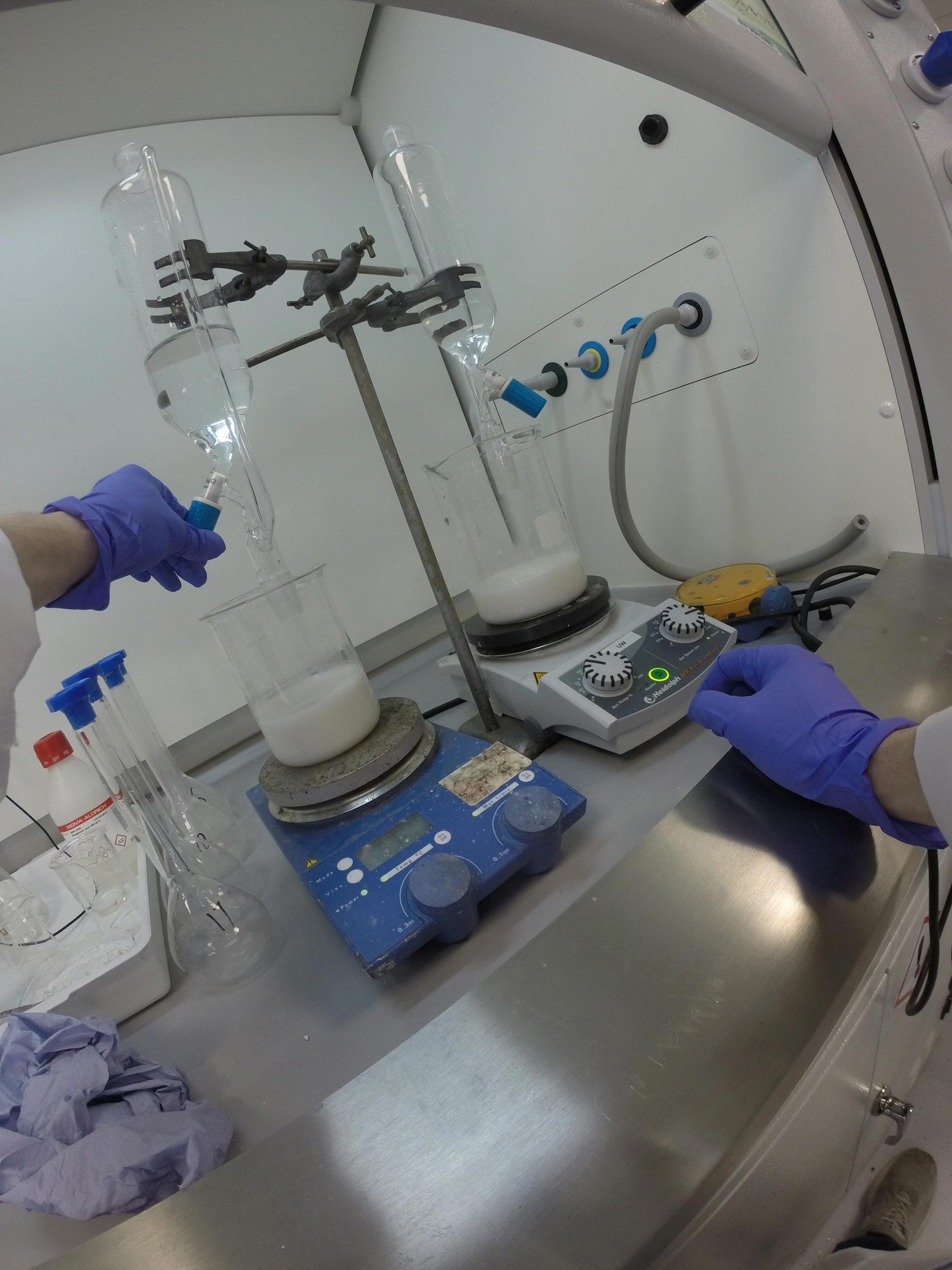

Phosphate Pigment

Phosphate Pigment

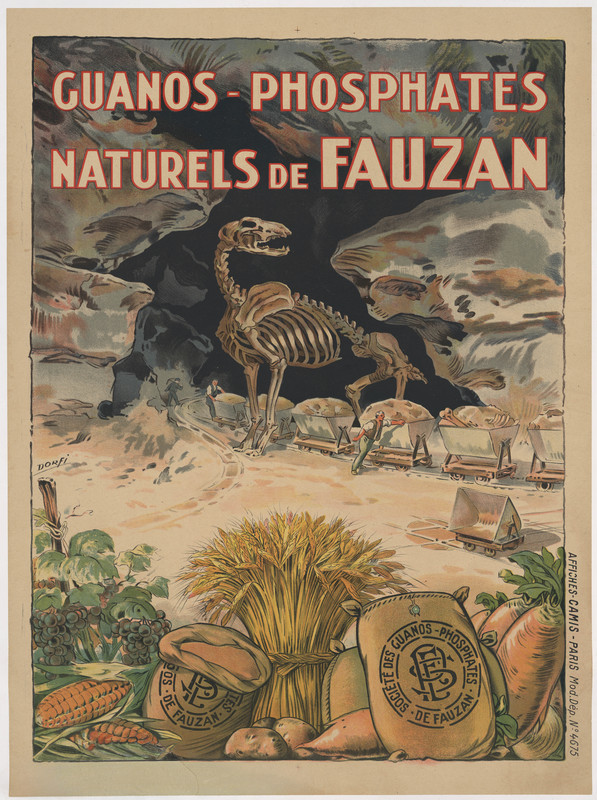

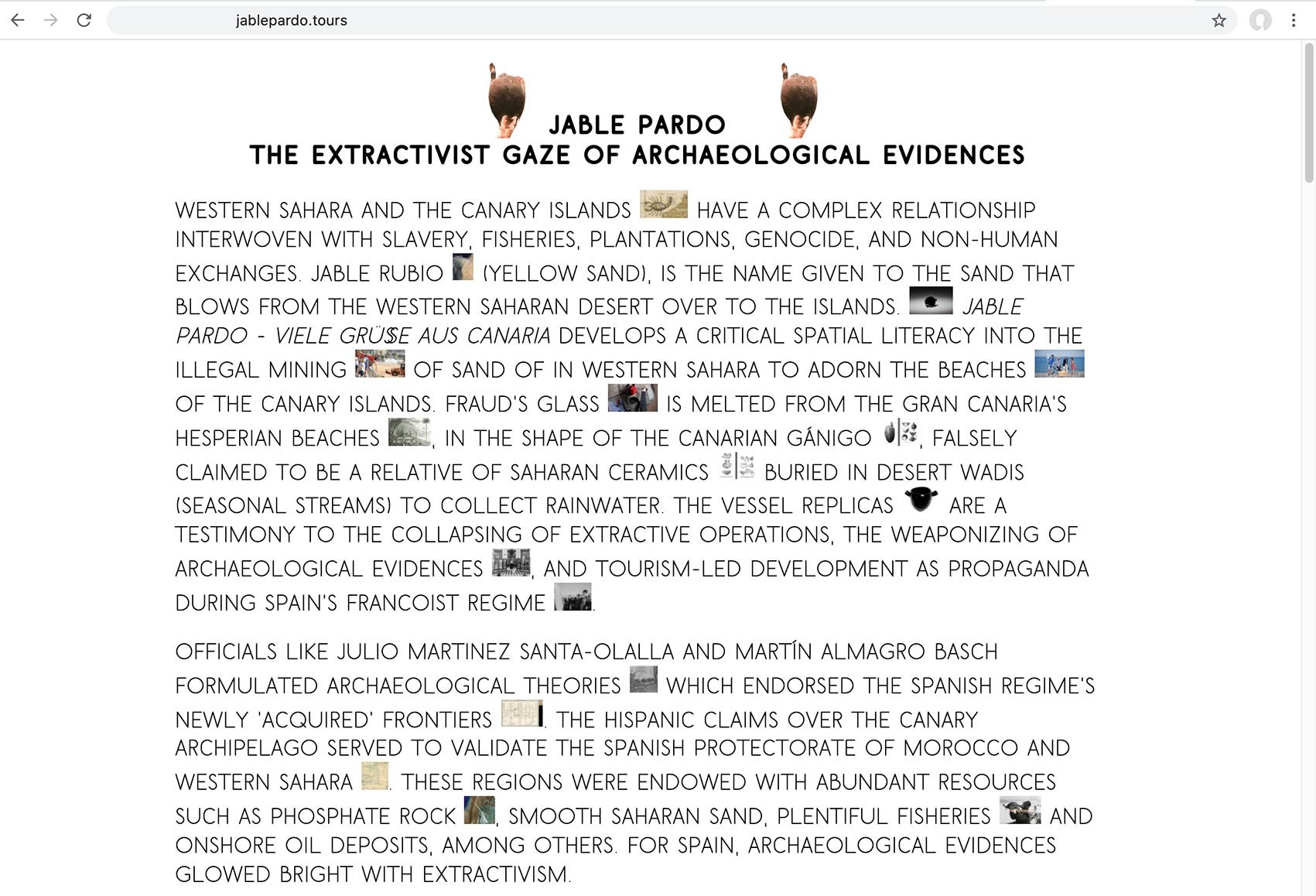

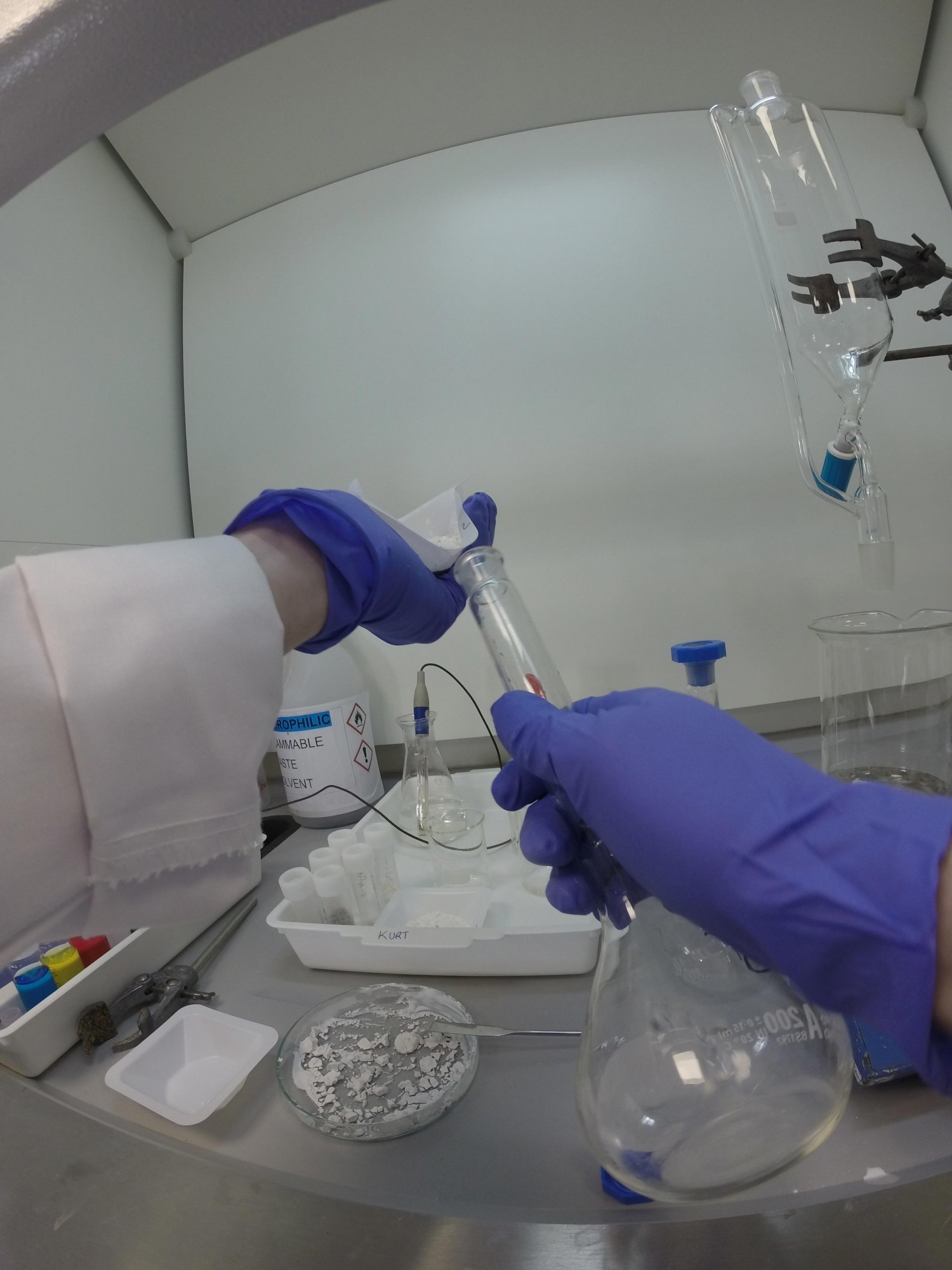

Phosphate is listed twice in the EU CRM list, under 'Phosphate Rock' and 'Phosphorus'. Phosphorus is mainly made from Phosphate Rock, and Phosphate is made of Phosphorus atoms combined with Oxygen. Phosphate rock is a finite, non-manufacturable resource whose global demand was carved by the Green Revolution’s crave for synthetic fertilizer. It is now a resource critical for the normal operation of agrobusiness. 71% of the world’s fertiliser comes from Western Sahara, currently occupied by Morocco, mostly from the Bou Craa mine. Western Sahara was occupied by Morocco immediately after gaining independence from Spain in 1975. Franco's regime sold its occupied territories for fisheries' rights and phosphate operations in the Bou craa mines. The dependancy to this mineral is thus tightly embroiled with (im)possibility of self-determination for the Saharawi people, who have largely lived in exile, in camps along the Algerian border since 1975.

In addition to its use in fertiliser, phosphate is the basis of the elemental phosphorus. Phosphorescence, a property of phosphorus in which light emission occurs over an extended period, is the oldest known chemiluminescing system. Phosphorus is also an essential mineral for the functioning of the human and more-than human bodies (stored with calcium in bones). The phosphate mines are the result of very old marine life deposits (fossilised bone). Thus, phosphate embeds a unique set of qualities and inherent tensions; it can emit light under certain conditions, and it is essential to the possibility of life while being equally central to its precarity.

As a means of 'staying with the trouble' of critical minerals, we have been working with Prof. Sandie Dann in the Chemistry Department of Loughborough University to develop a phosphorescent pigment made with the phosphate used in British fertiliser which is mined in Morocco (Bou Craa mine in Western Sahara) and Tunisia (Gafsa).

…

Décollage

Décollage

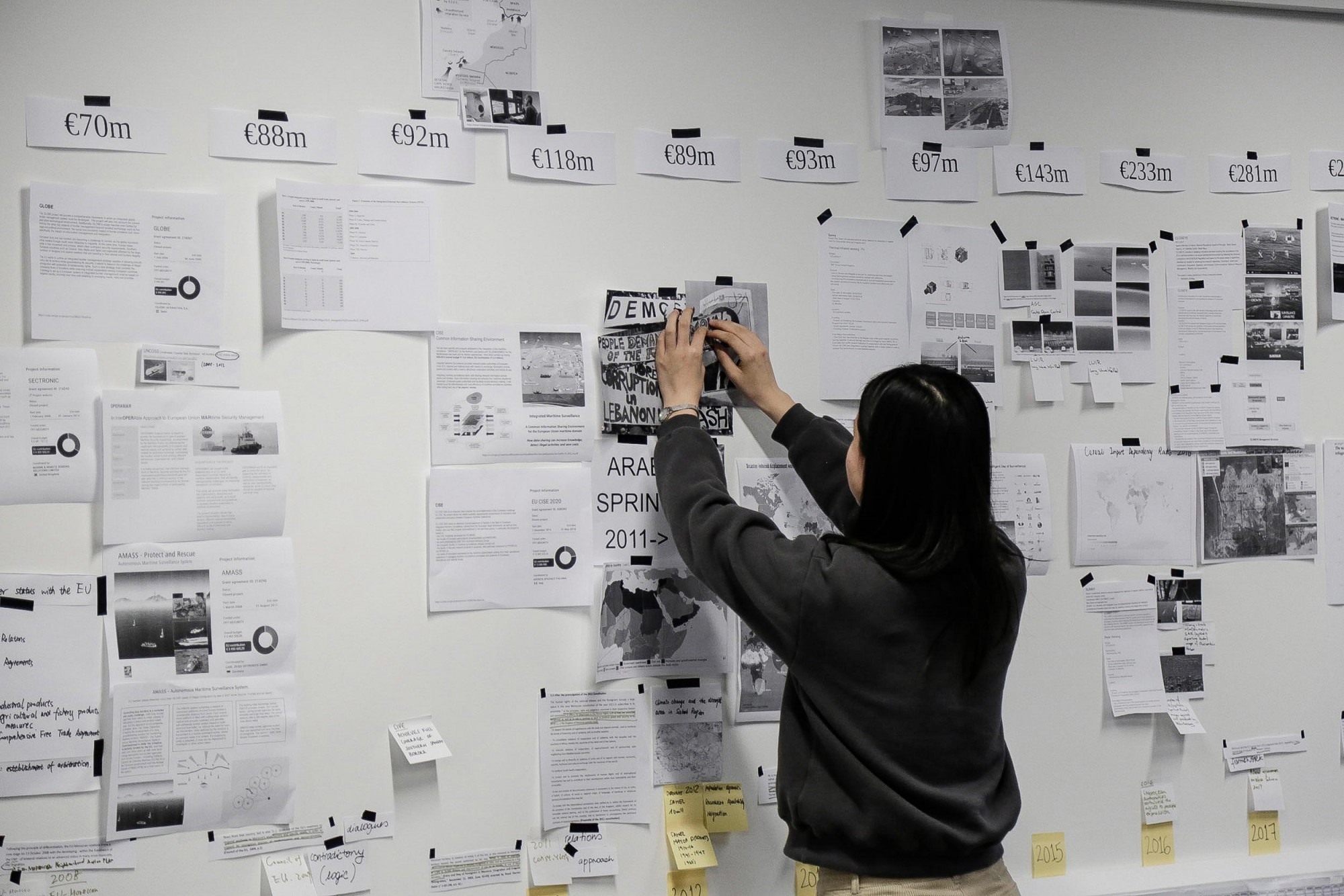

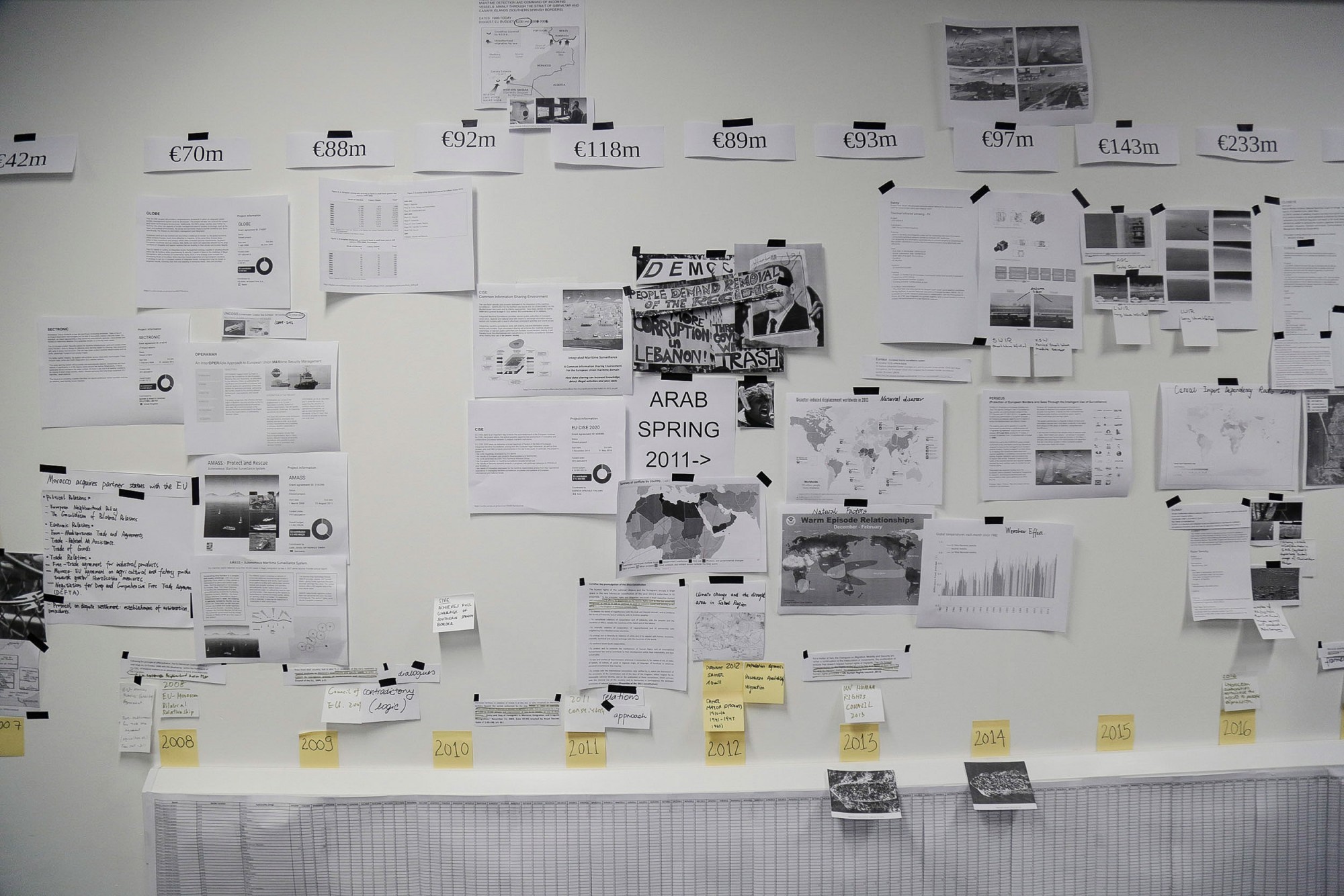

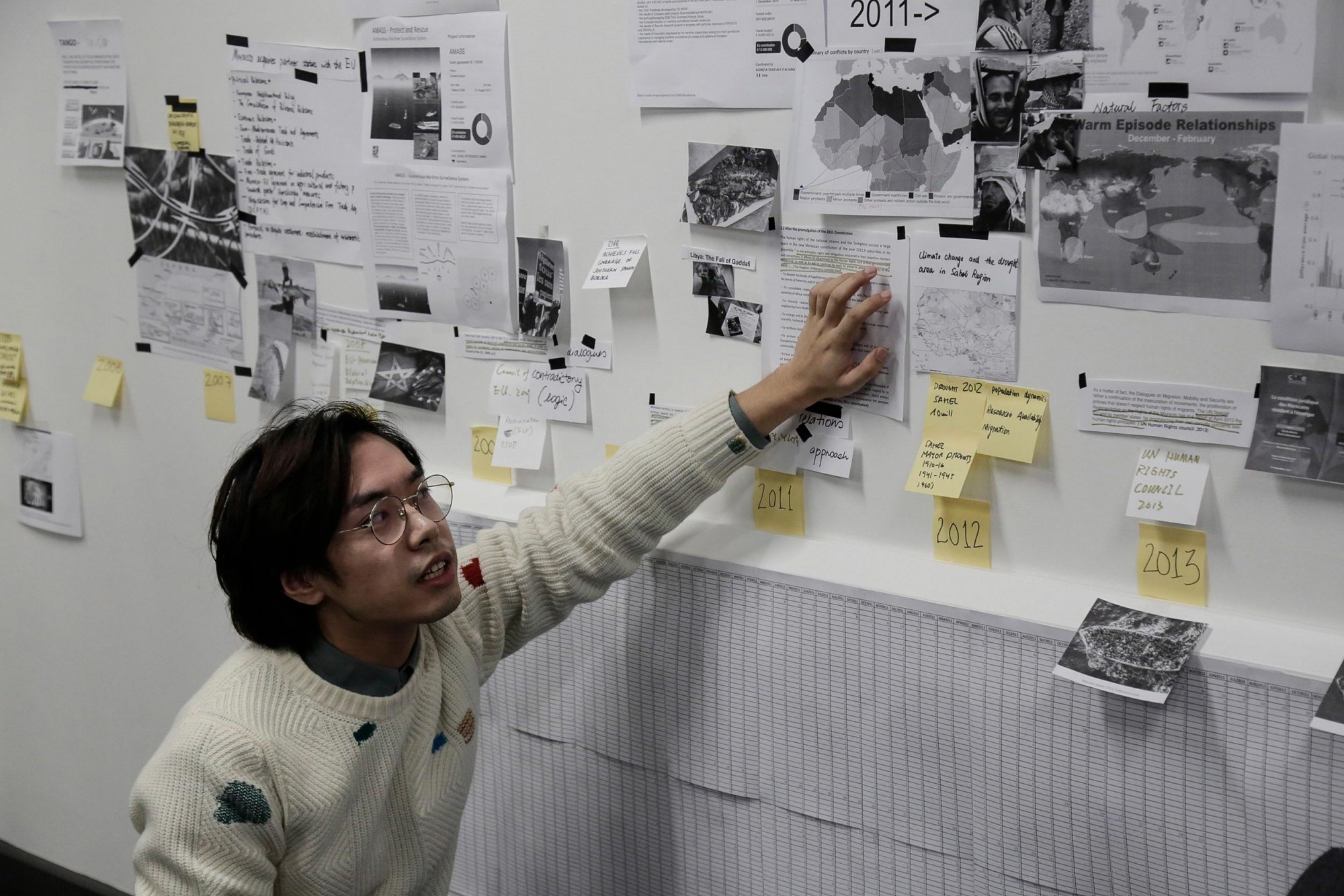

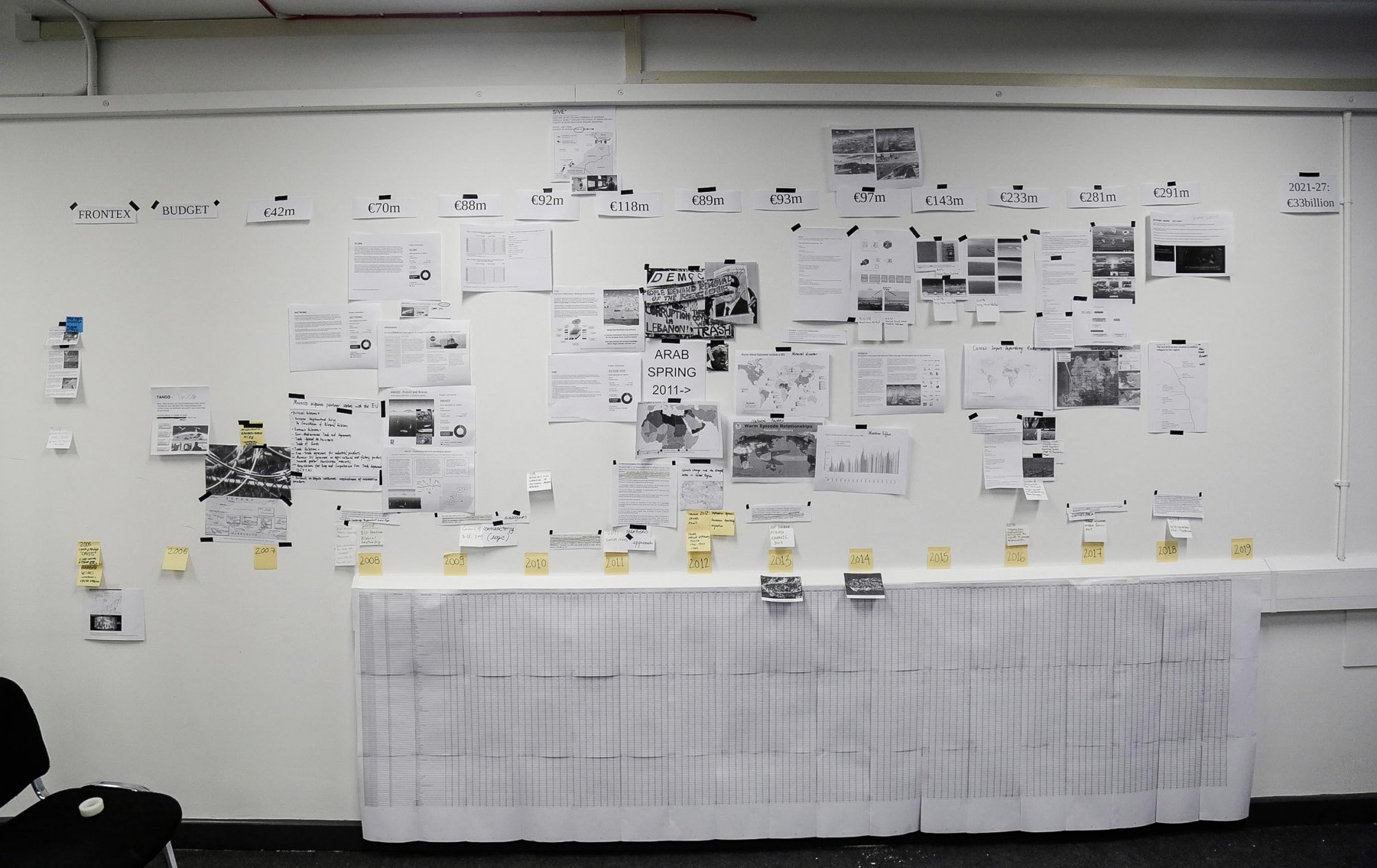

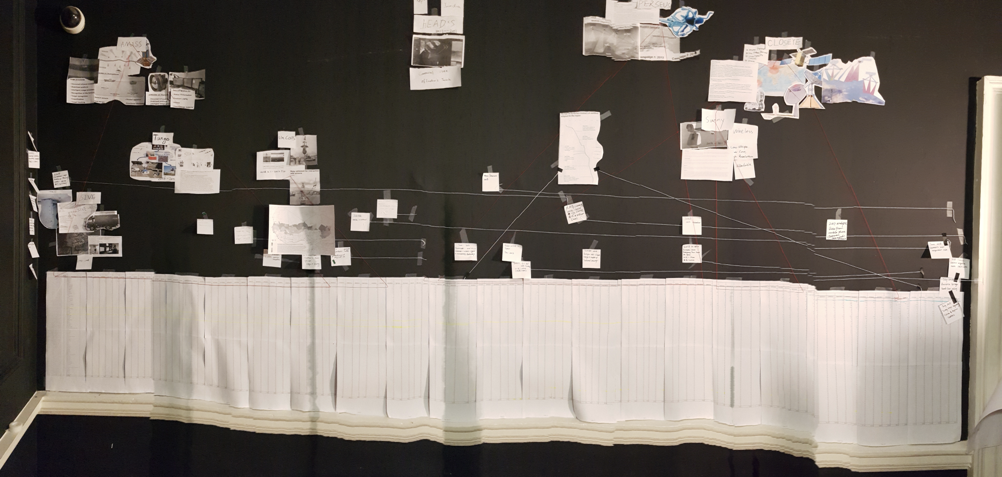

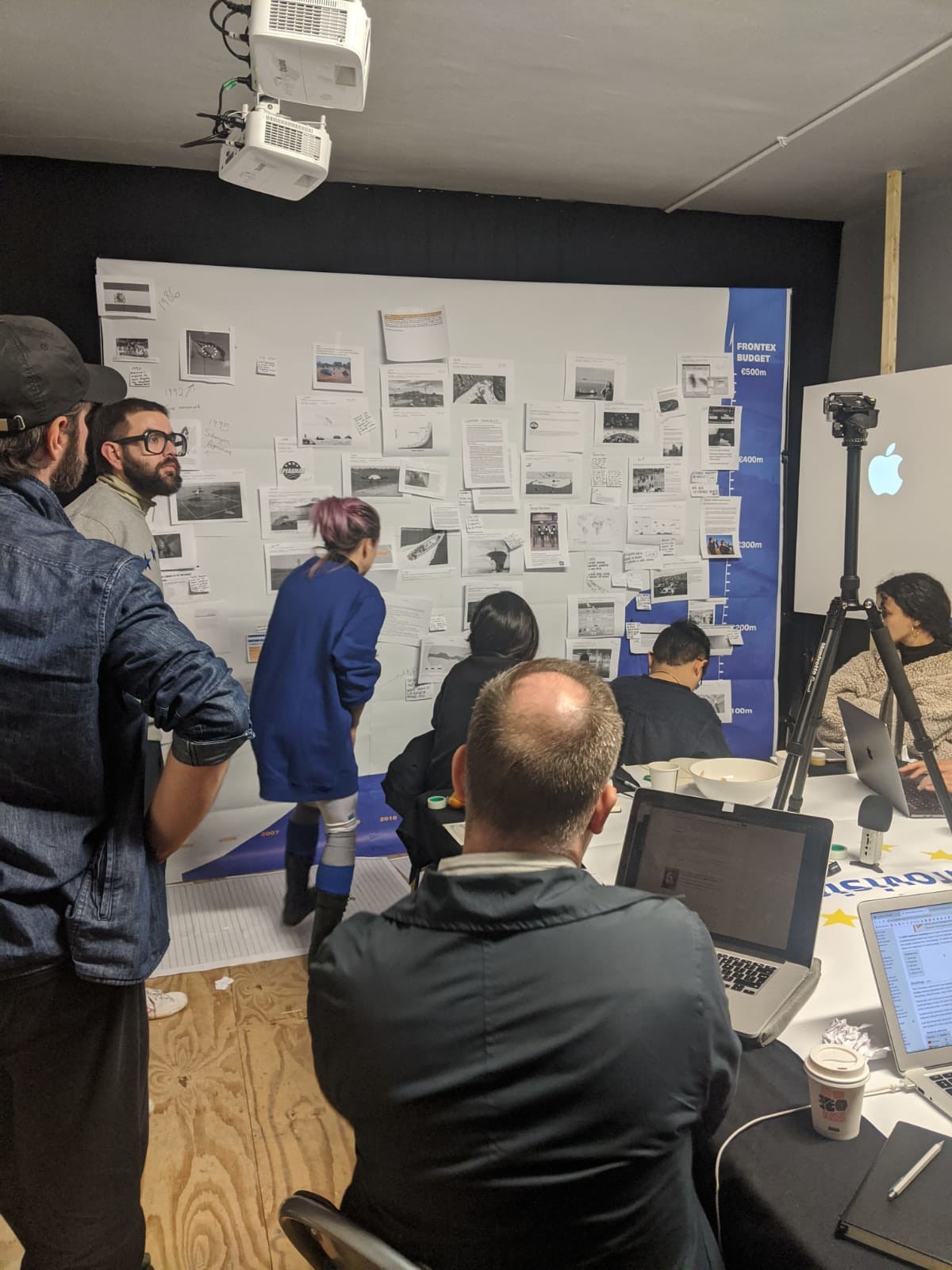

We have developed décollage as research method, based on the artistic method that usually consists of multiple layering which are then selectively ripped off. Fluxus artists popularised this method, namely artists such as Wolf Vostell.

The uncovering that is central to décollage is the basis for its reappropriation as an artistic-research method. Décollage inscribes itself within critical technical practice, concerned with revealing obfuscated material conditions of production and to critically chart affective modes of power entangled in a specific issue. As a pedagogical model, it is a collaborative, interactive tool which affords the broaching of complex and otherwise potentially overwhelming issues, to understand the multiplicity of factors and their interconnectedness.

In its essence, décollage is a method to approach and unpick a multifaceted subject. We use multiple divergent lenses to study a specific issue. These are grouped in ‘research islands’. Participants in each island delve into their area of the topic, and place their findings along a timeline that is common to the entire group. The convergence of items on the timeline form clusters, or patterns, which make visible intricate connections between seemingly disparate elements. These observable relations form the basis for further discussion, research and/or artistic response. Examples of student outputs from previous décollage workshops include discussions, a glossary, a booklet, a cooking show, and a conveyor belt.

-

See Patricia Reed's musings on complexity in Constructing Assemblies for Alienation. Mould Issue #1, eds. Markus Miessen, Milan: Mould Press, 2014. ↩

…

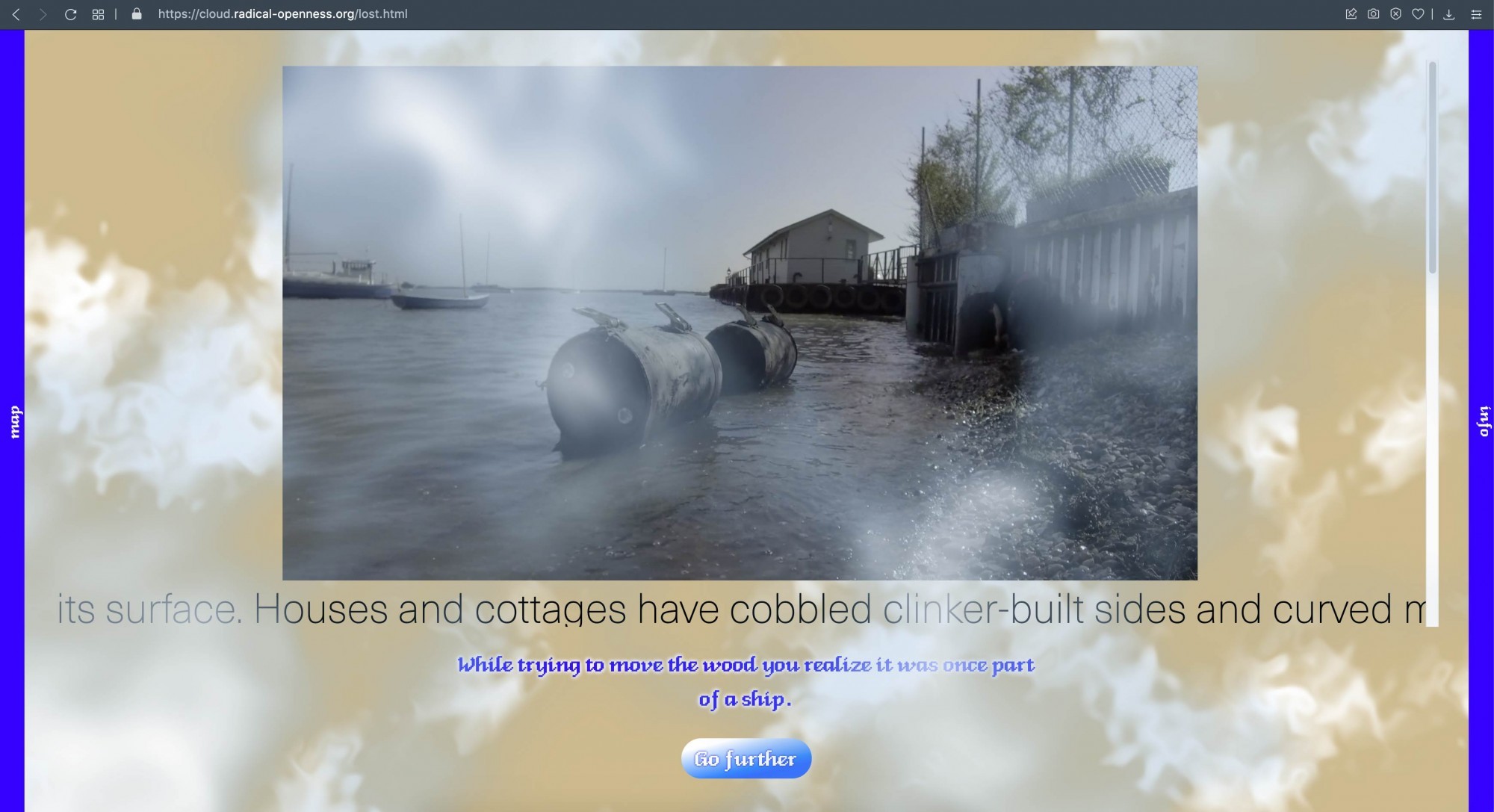

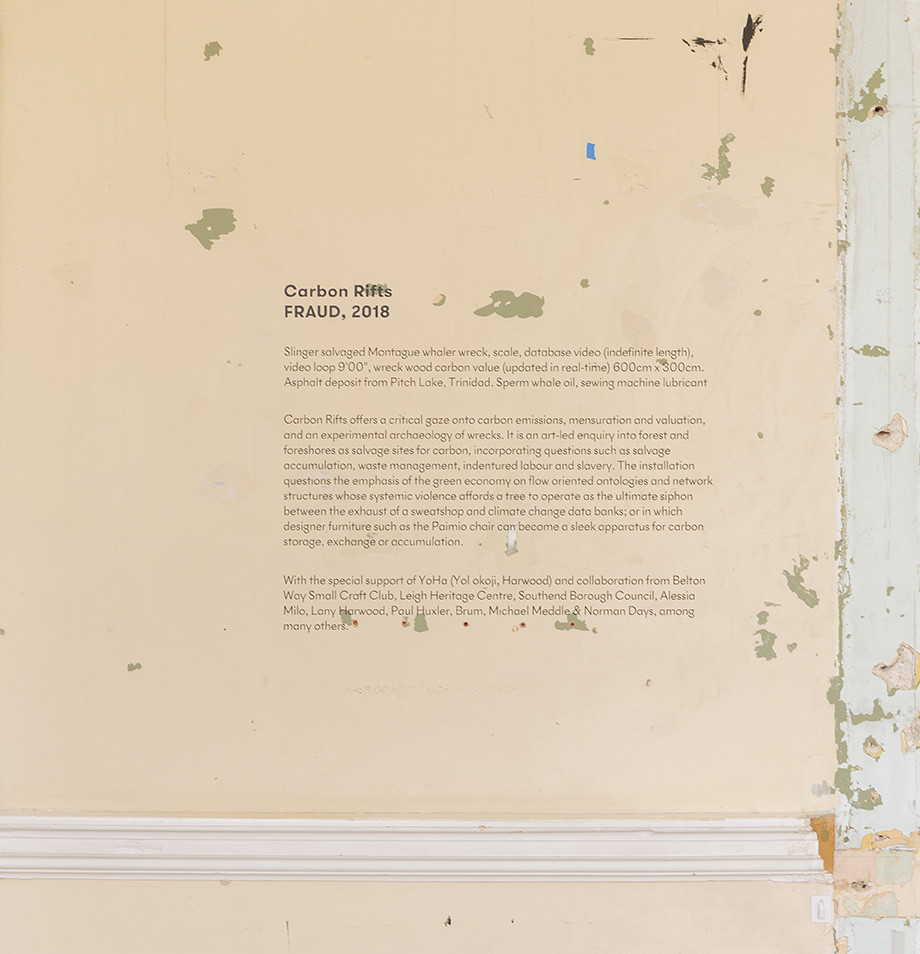

Carbon Rifts

Carbon Rifts

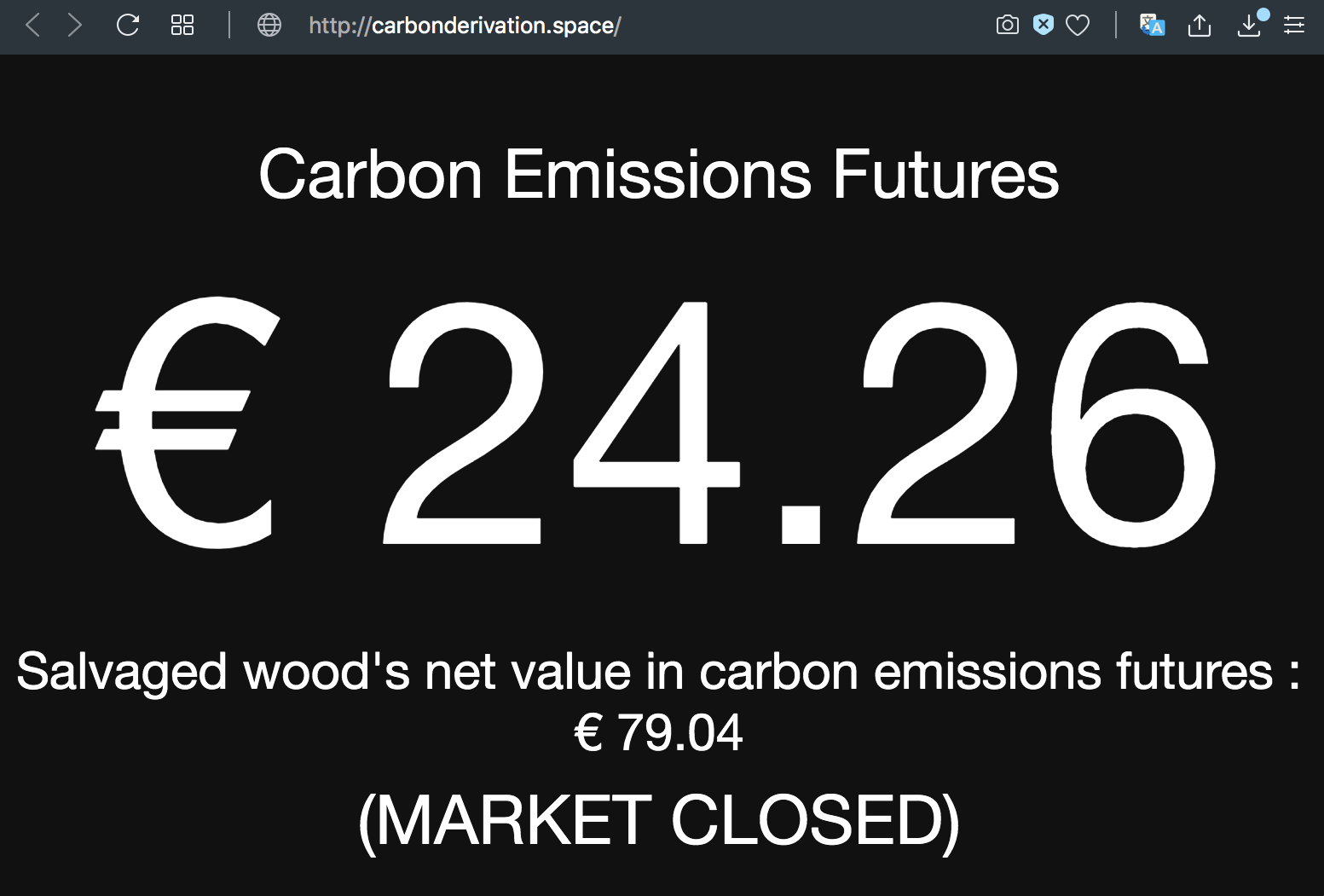

See online Carbon Rifts interface.

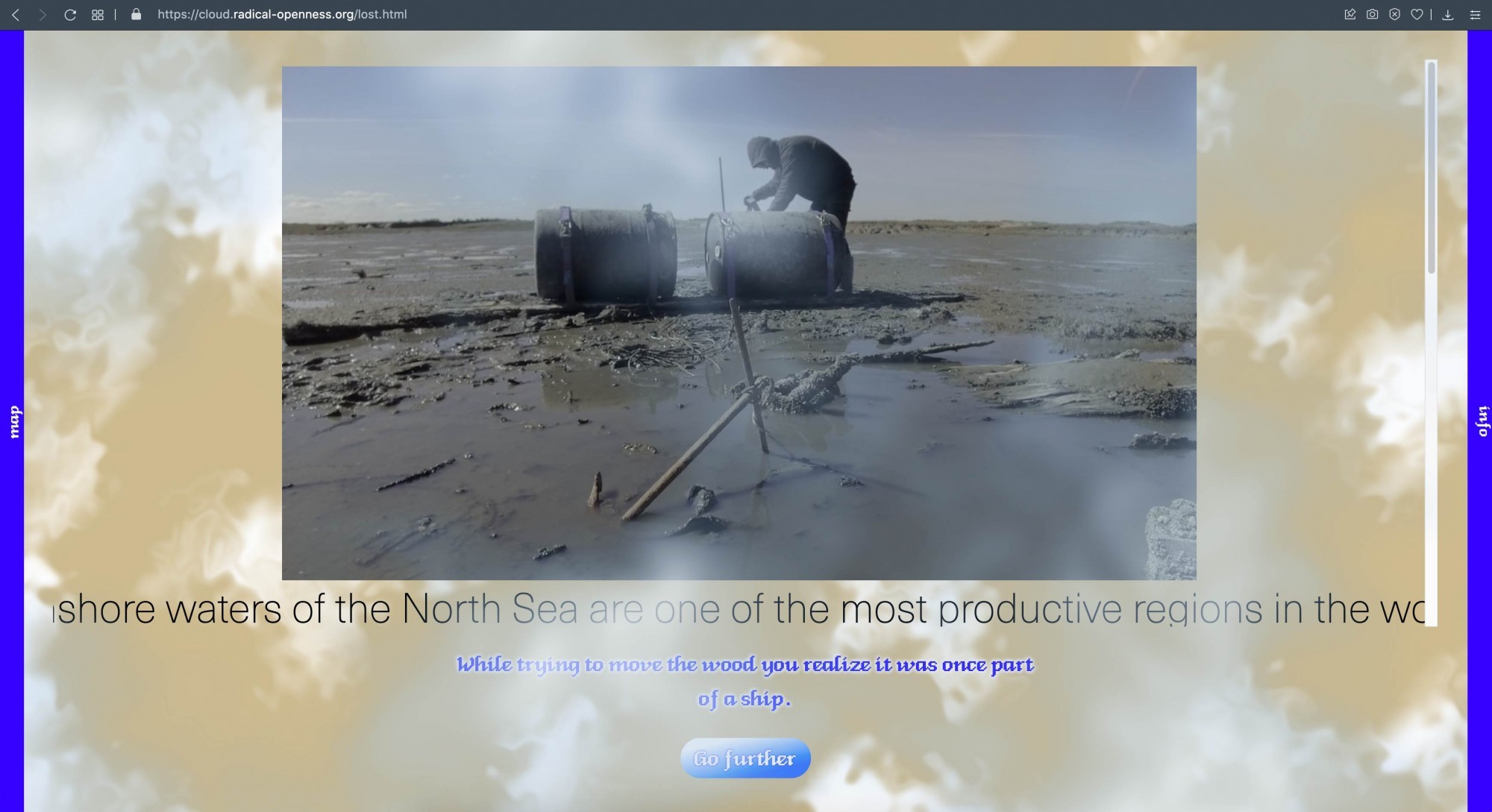

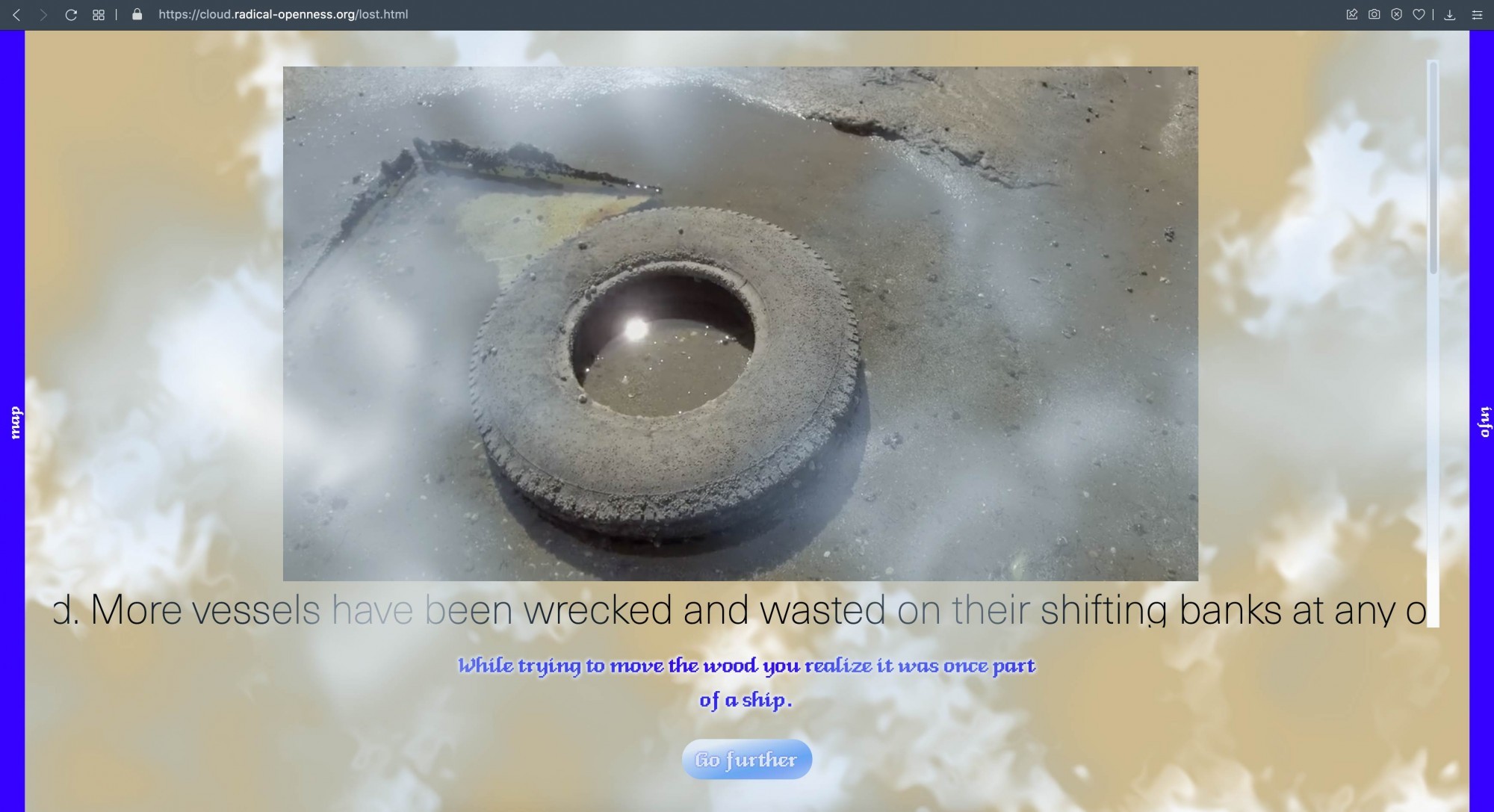

His approximate computation: 550 crafts per year: 1.5 per day on average. At any given moment, more boats lay wrecked than are circumnavigating its surface. An 80-guns ship required 2000 tons of wood, a forest like Epping in Essex would be consumed by building only 60 top rate ships at a rate of 40 acres of forest per vessel. As Britain's submerged forests are still vaster than the standing ones, and the carbon market has become the world’s largest commodity market. These humped shoals emerge as Britain's biggest carbon derivative.

…

Indulgentia

Indulgentia

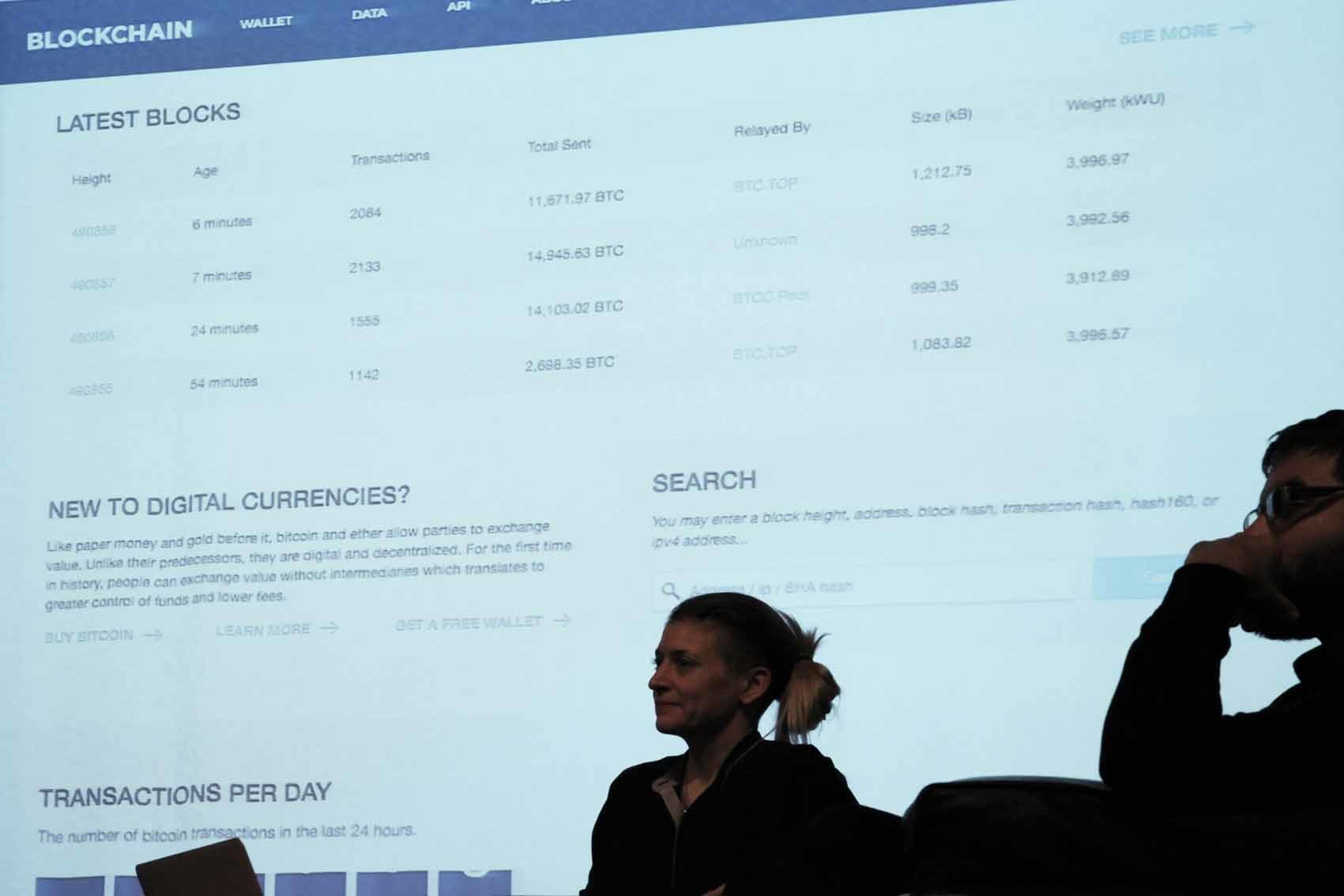

Indulgentia launched its initial coin offering with ‘Carbon Derivatives’ at the Palazzo Trevisan degli Ulivi in Venice on October 20th, 2017.

The Indulgence Coin engages with material and cultural discourses that legitimise green trade and the affective powers that emerge from it. The current epoch undergoing northern climate change and globalised anthropogenic impact can be putatively defined by the affective power embedded in flows of carbon and carbon derivatives: hydrocarbons fueling engines or metabolic processes, and financial trading systems such as green bonds, or emissions trading systems (ETS).

Utilising trees as carbon storage has the effect of abstracting their biological function to a commodity for the service economy, framing carbon as both material and economy. This argument facilitates the replacement of boreal forest by industrial forests, with more efficient carbon yield. In turn, these efficient storage sites increase a country’s collateral for the emissions trade.

This carbon market is contentiously emerging, while simultaneously destroying ecosystems and indigenous knowledge systems.

Indulgentia harnesses the power of the blockchain to offer a decentralised and anonymous approach to carbon trading, while exploring the relationship between speculation and carbon resources.

History of indulgentiārum

Indulgences were awarded by the Catholic Church as a remission of sin through a donation of money in the Middle Ages. The copious repenting of sinners funded the crusades (such as those against the ‘Turkish invasion’ of Venice) as well as the building of such monuments as the St Peter's Basilica. Indulgences are also the earliest dated printed European document by movable type, made possible by the Gutenberg press. The later printed indulgences as a side job while working on the Bible. It has been suggested by H.D.L. Vervliet that the invention of the press itself may have been prompted by the recognition of the need for large numbers of identical Indulgentia documents. With the printing of Indulgentia also emerged the automisation of labour rendering large amounts of scribes redundant.

Thus, the notion of capitalisation on repentance and deskilling labour is nothing new. Tried, tested and true, these have repeated throughout history and once again with carbon trading. As Richard Sandor tells us, with good derivatives “You CAN Put a Price on Nature”. Carbon credits emerged as a way to include ‘nature’ in the balance sheet, to insure that it would not be overlooked as a resource. Since these humble beginnings, the carbon market is projected to become the world’s largest commodity market by 2020. To ensure that companies do not resort to ‘carbon leakage’, that is to shift production to countries with less ambitious climate measures, manufacturing industries thought to be at risk of carbon leakage get free emission allocations. Free indulgence masked as emission control. Because industrial sectors are receiving more free pollution permits than the amount of CO2 they emit, which they then sell, they incur windfall profits. In short, speculation and EU regulations have facilitated the transfer of money from taxpayers to industry to the order of billions of EUR.

…

Tar Sorbet

Tar Sorbet

2 (13- to 15-ounce) cans full-fat coconut milk

1/2 cup sweetener, such as agave syrup, maple syrup, honey, turbinado sugar, or cane sugar

1/4 teaspoon salt

2 tablespoons cornstarch, or 1 tablespoon arrowroot starch

1 1/2 teaspoons flavour extract

Tar flavour (0.5dl of terva)

1/4 cup activated charcoal

…

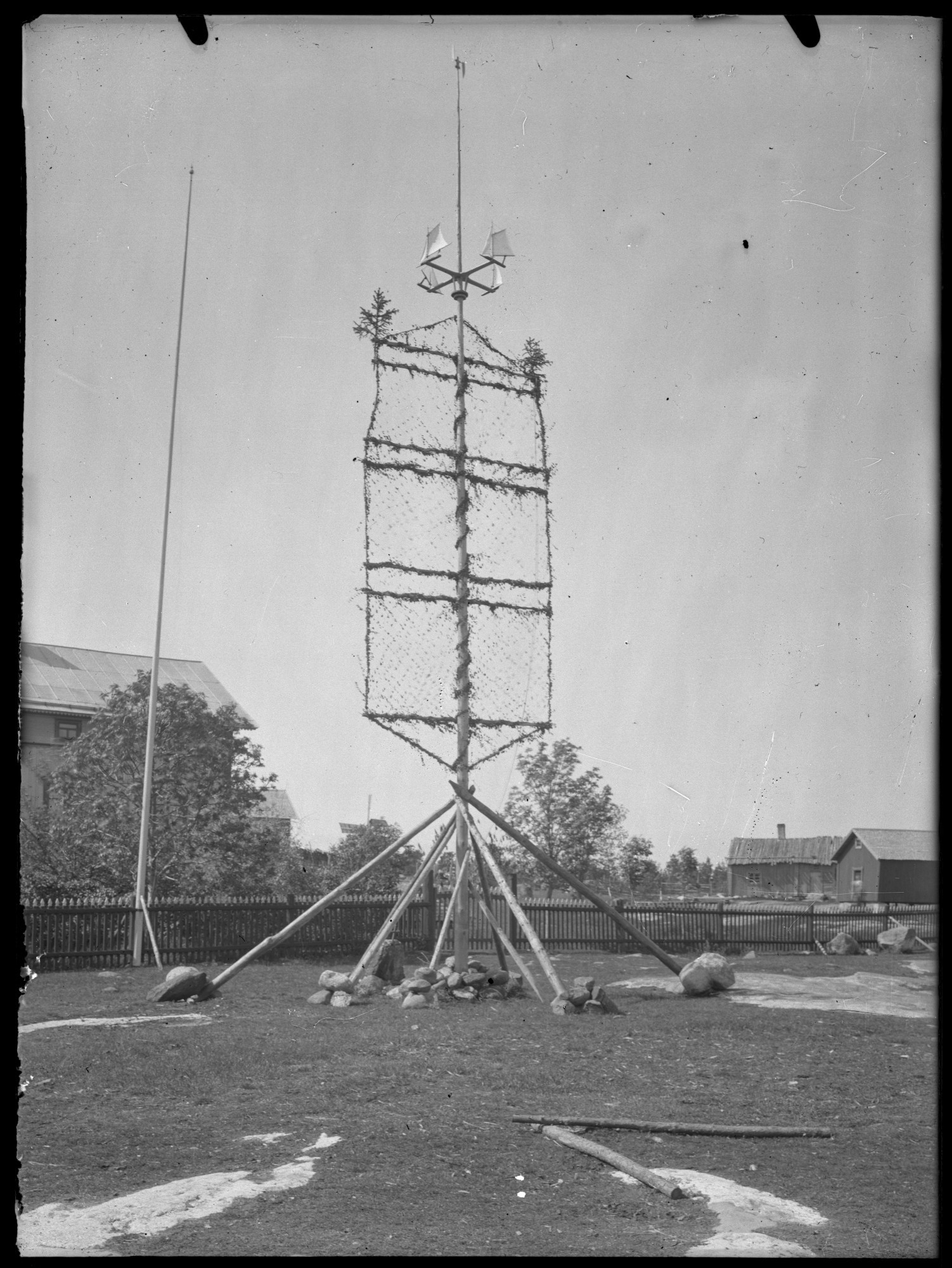

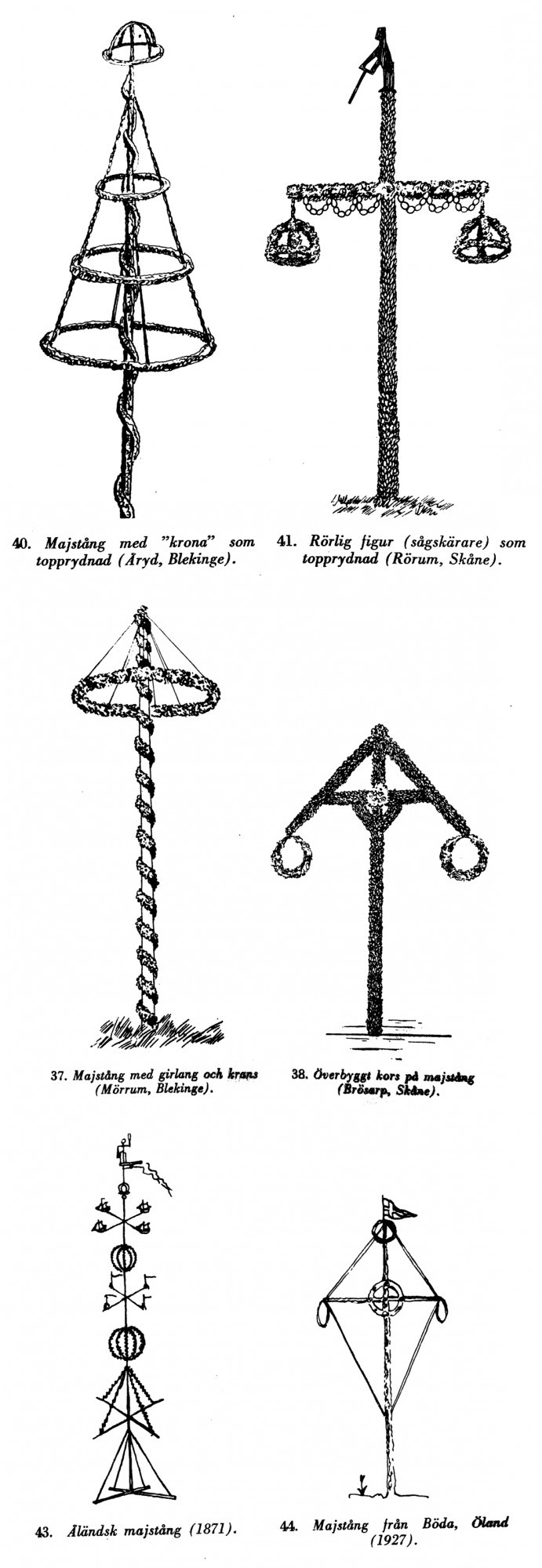

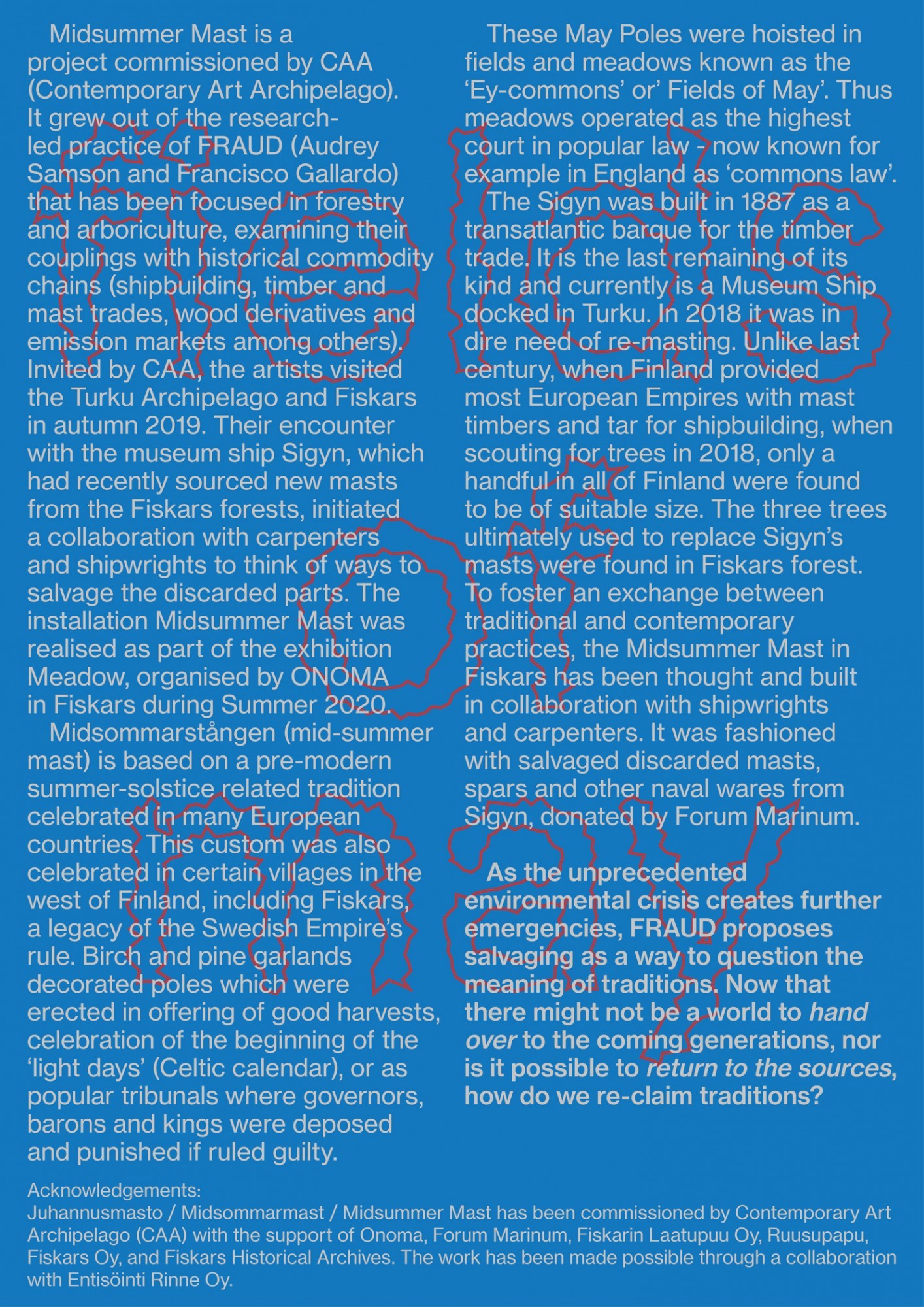

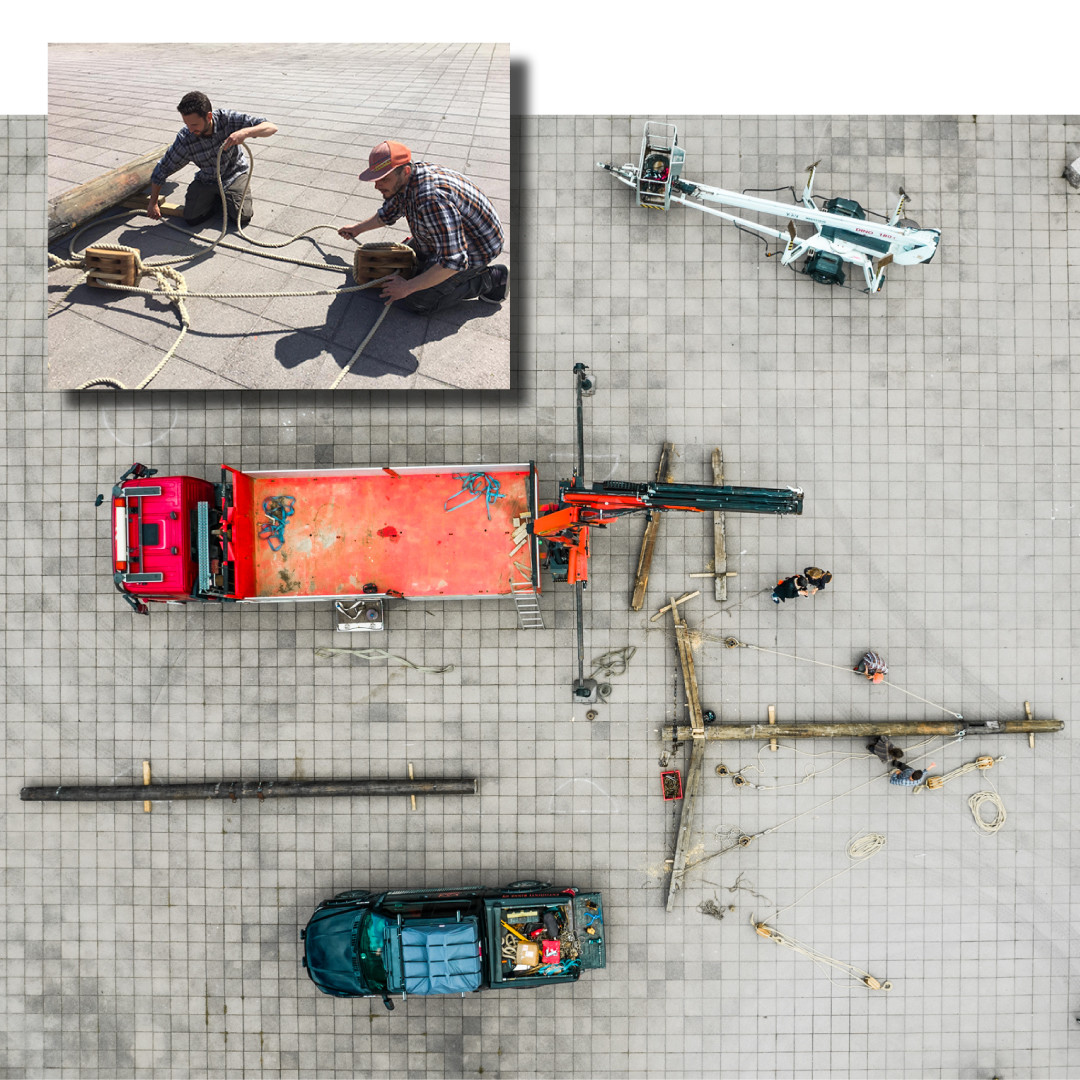

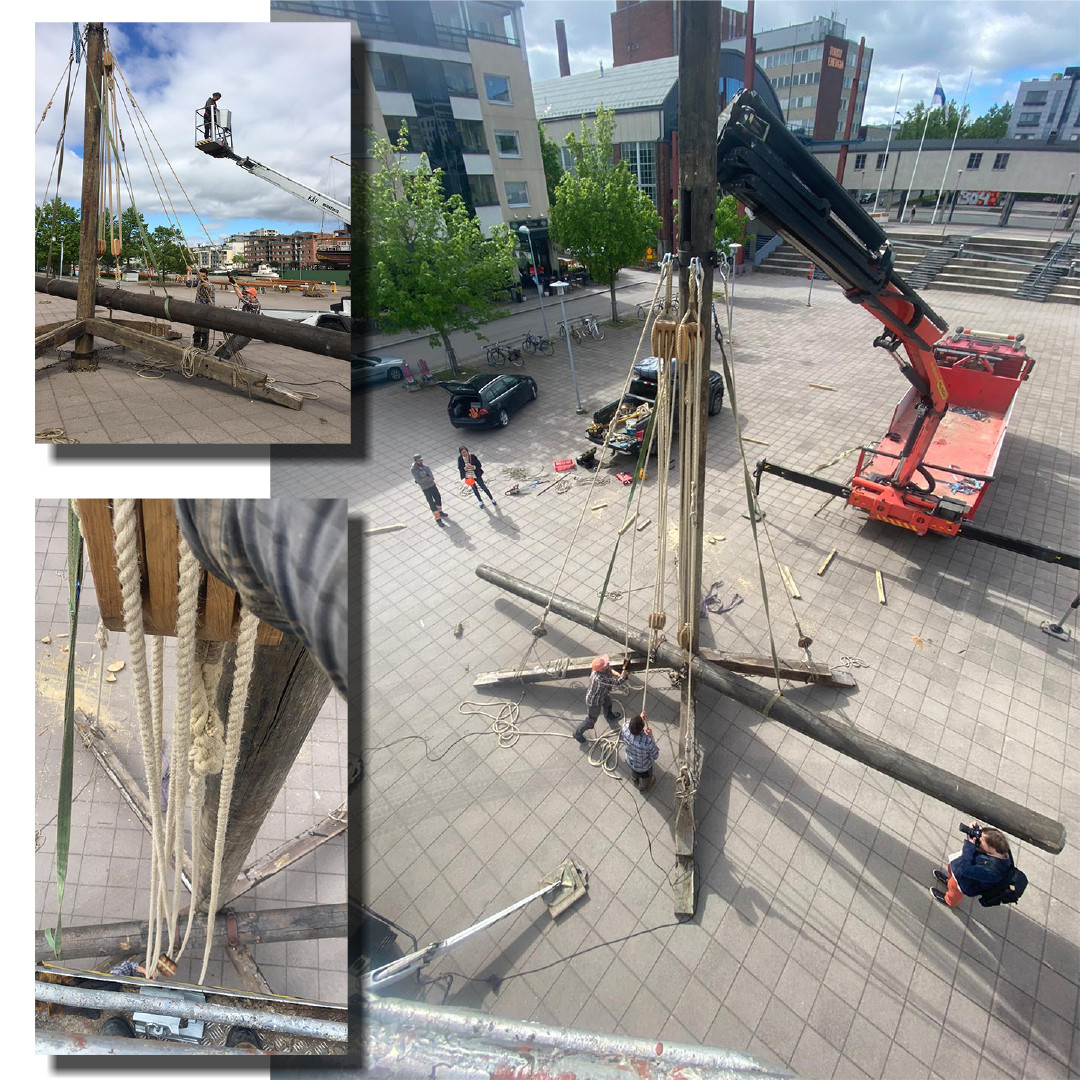

Midsummer Mast

Midsummer Mast

Midsummer Mast grew out of a research-led practice focused in forestry and arboriculture, examining their couplings with historical commodity chains (shipbuilding, timber and mast trades, wood derivatives and emission markets among others). Invited by CAA,

Context:

The mid-summer pole is a pre-modern summer-solstice related tradition celebrated in many European countries. This custom was also celebrated in certain villages in the west of Finland, including Fiskars, a legacy of the Swedish Empire’s rule.

Birch and pine garlands decorated masts which were erected in offering of good harvests, celebration of the beginning of the ‘light days’ (Celtic calendar), or as popular tribunals where governors, barons and kings were deposed and punished if ruled guilty. These May Poles were hoisted in fields and meadows known as the ‘Ey-commons’ or’ Fields of May’. Thus meadows operated as the highest court in popular law - now known for example in England as ‘commons law’.

The Sigyn, built in 1887, needed new masts in 2018. This wooden barque that crossed the oceans and seas for trade a hundred years ago, the last remaining of its kind, is now a museum ship in Turku. Unlike last century, when Finland provided most European Empires with the timber and tar to build their fleets, when scouting for the mast material in 2018, only a handful of trees in all of Finland were found to be of suitable size. The three trees ultimately used to re-mast Sigyn were found in Fiskars forest.

To foster an exchange between traditional and contemporary practices, the mid-summer mast in Fiskars has been conceptualised and built in collaboration with shipwrights and carpenters. It is made from salvaged discarded masts, spars and other maritime wares from the Sigyn, donated by Forum Marinum.

As the unprecedented environmental crisis creates further emergencies,

The work was supported by ONOMA, Forum Marinum, Sigyn Foundation, Fiskarin Laatupuu Oy, Ruusupapu, Fiskars Oy, and Fiskars Historical Archives. The work was made possible through a collaboration with Entisöinti Rinne Oy.

Acknowledgements:

A great many individuals have contributed to this project, we extend our gratitude to: Heikki Aska, Taru Elving, Emilia Hänninen, Matleena Kalajoki, Elias Lähdesmäki, Tommi Lavonen, Robert Louhimies, Tapio Maijala, Ville Poikola, Atte Pylvänäinen, Tuomo Rinne, Jukka Salo, Tapio Santala, Kenneth Silver, Saskia Suominen, Rhys Thomas, and Hanna Utriainen.

Main background image: Stump of larch tree in Fiskars forest which was cut to remast the Sigyn ship in 2018. Only a handful of suitably sized trees were available in all of Finland.

Main background image: the old mast donated to

↓

Exhibitions

…

Istanbul Design Biennale

Istanbul Design Biennale

Partnerships is a research-led archive which engages with the EU-Morocco Fisheries Partnership Agreement and its devastating effects upon ‘extra-Mediterranean’ marine life, such as the exhaustion of fish stocks and local fisheries. Contextualised within a broader framework that examines the genealogy of the European Union’s extractive capitalist gaze, it aims to cultivate the active, intercultural and critical building of a counter-colonial cosmogony.

Partnerships has been produced as part of the Library of Land and Sea in the 5th Istanbul Design Biennial – Empathy Revisited: designs for more one, organised by the Istanbul Foundation for Culture and Arts, and curated by: Mariana Pestana, Sumitra Upham and Billie Muraben.

We acknowledge the support of the Canada Council for the Arts and Arts Council England.

…

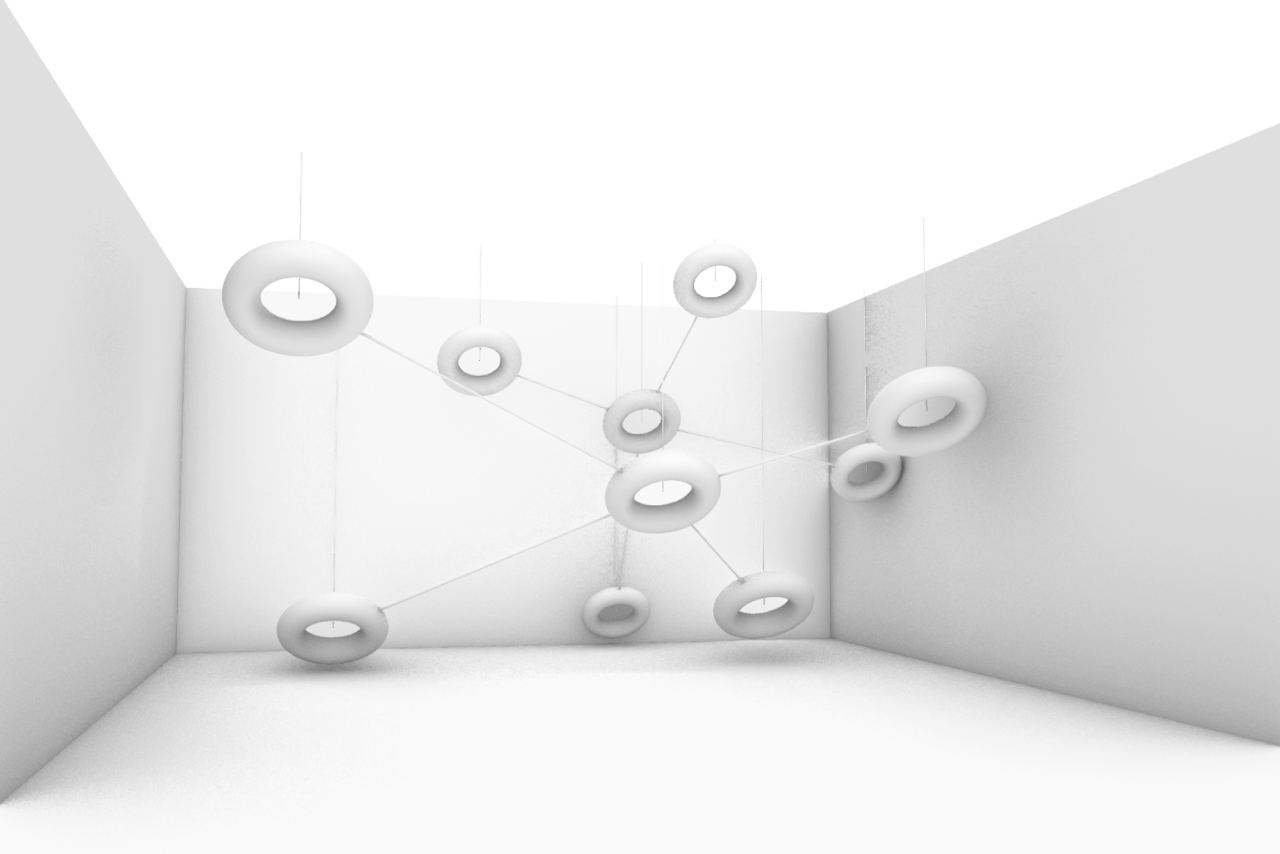

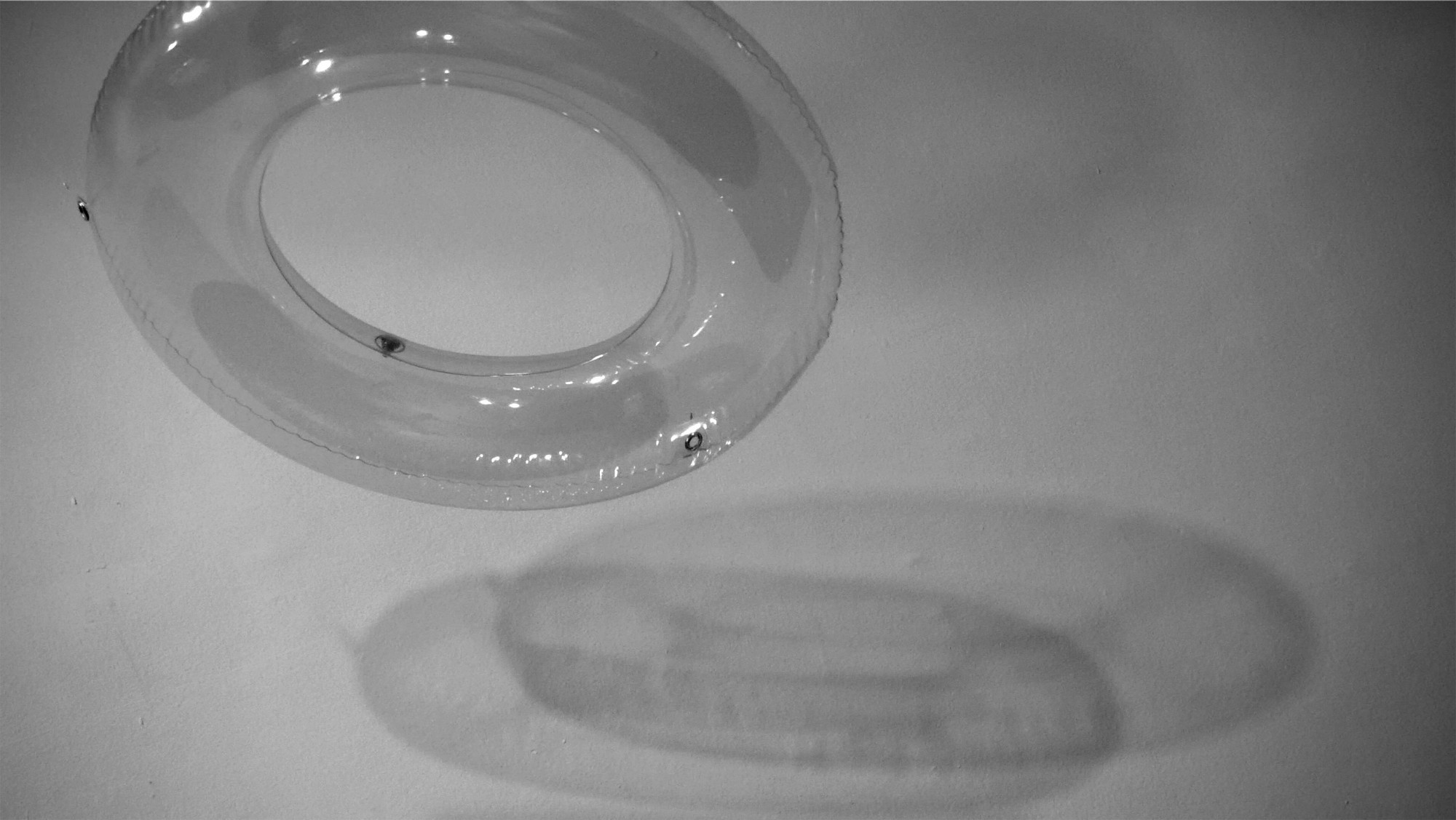

HBK Gallery

HBK Gallery

Further info: Jable Pardo

Acknowledgements:

Videographer: RYAN.MEDIA

Glass blowing: Torsten Rötzsch and Louise Lang

Art Handler: Sabrina Basten

With the incommensurable help of Manuel Ballehr, Sandra Bödecker, Clara Brinkmann, Hannah Jung, Peter Keyser, André Linpinsel, Martin Salzer, Keramik-Kraft, Western Sahara Resource Watch, and our Gran Canaria attaché.

With the mentorship of Prof Raimund Kummer, the support of HBK Braunschweig's BS Projects programme, and the Canada Art Council.

…

AMRO20 Festival

AMRO20 Festival

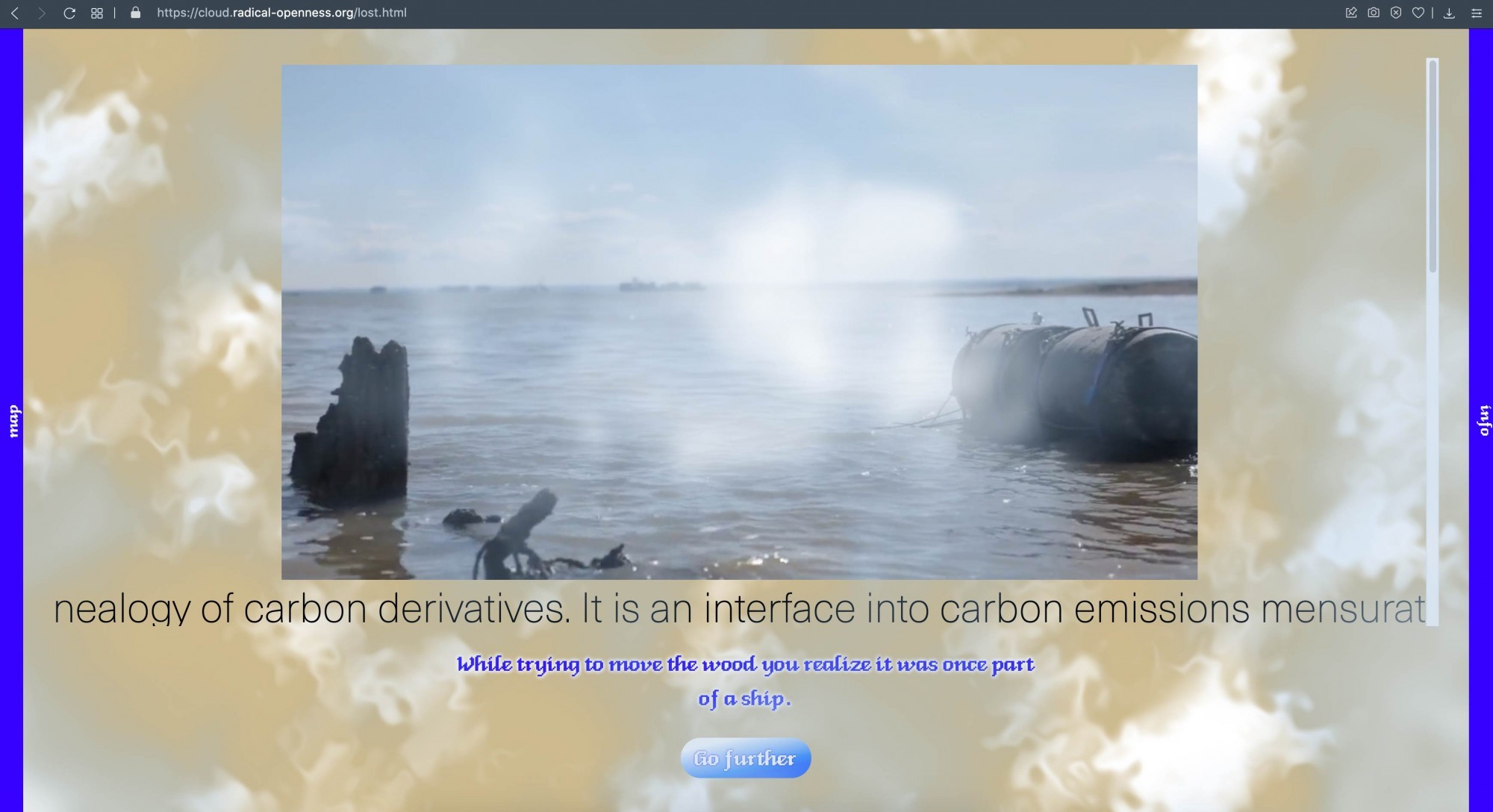

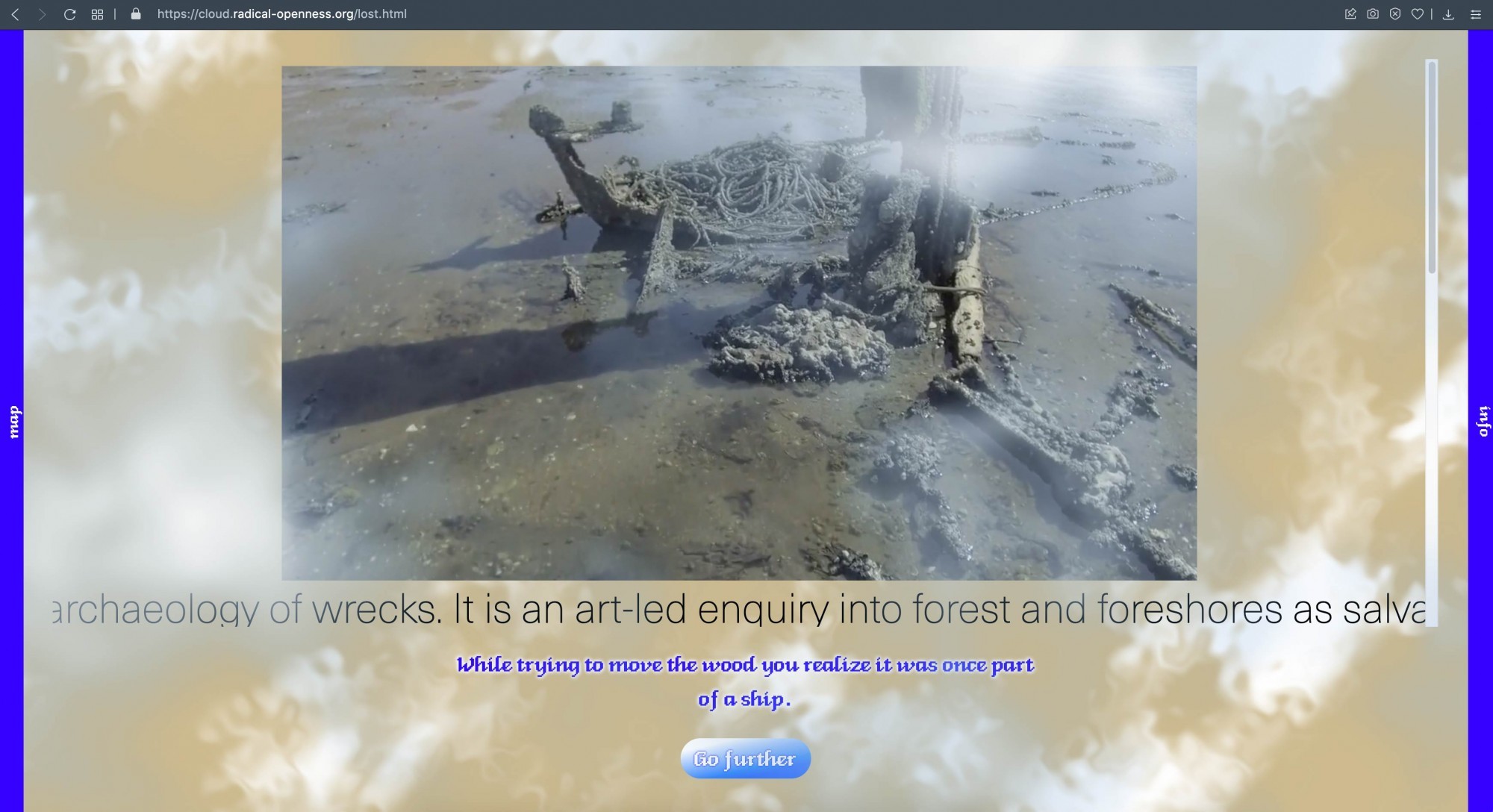

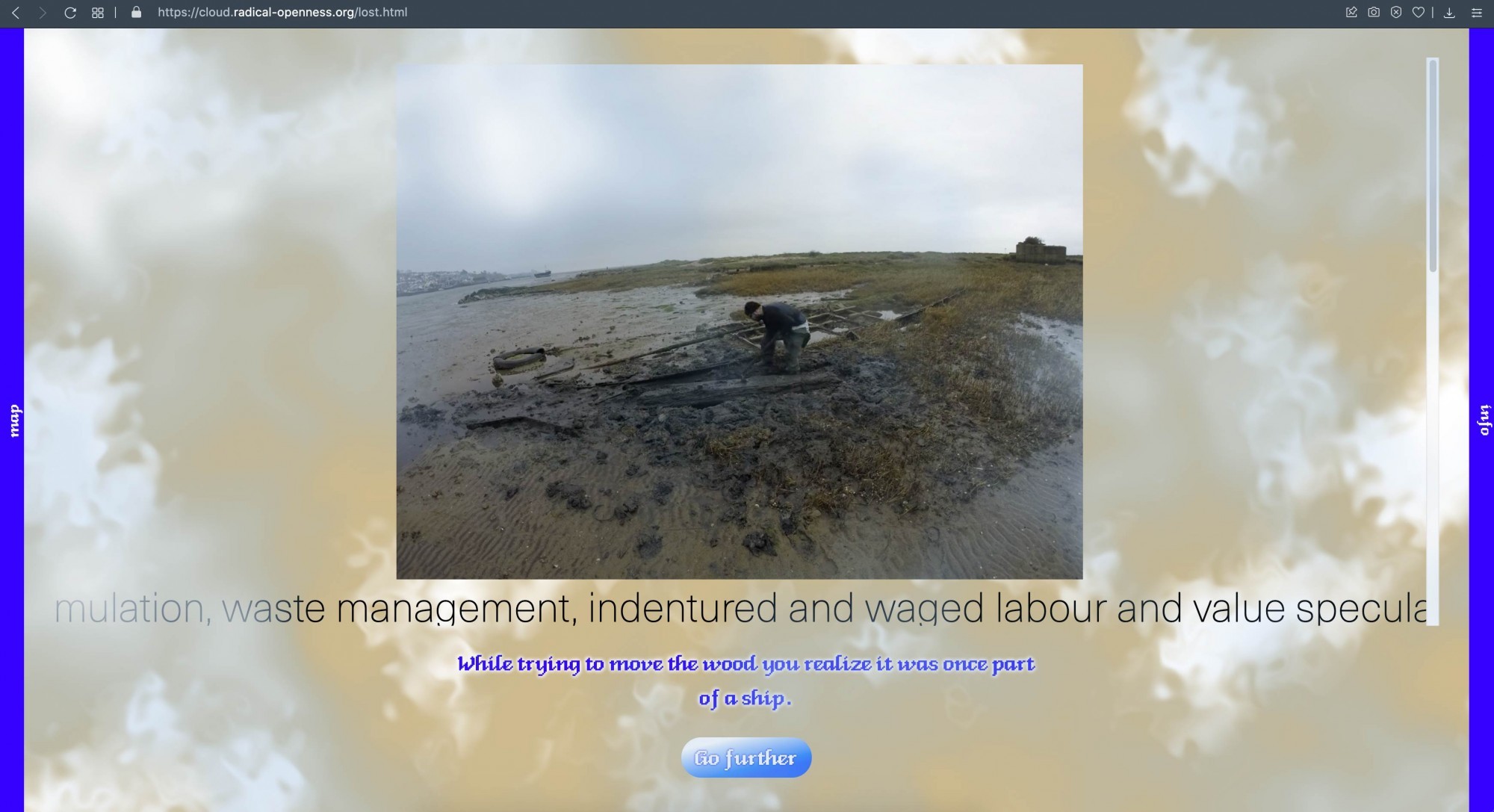

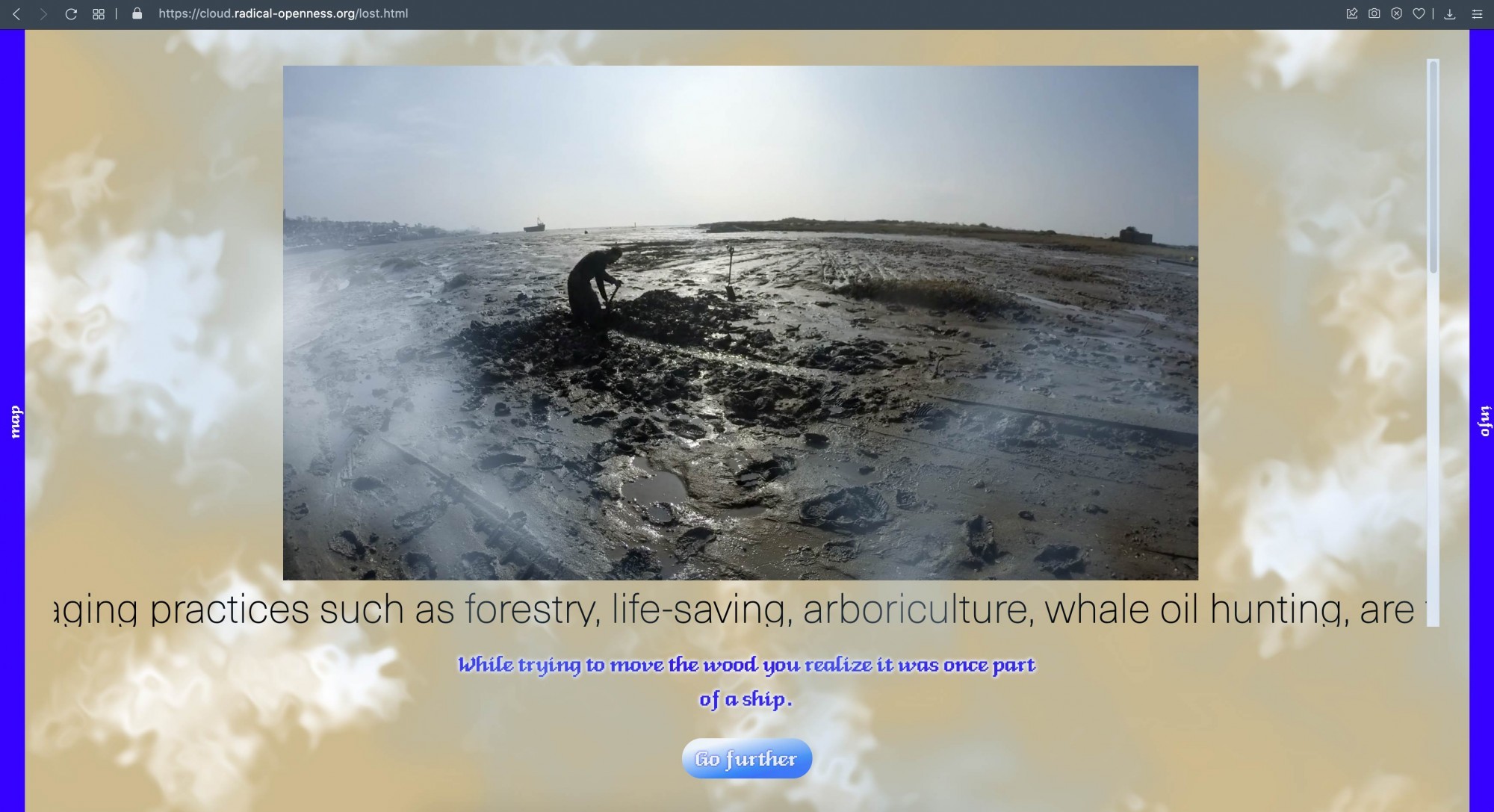

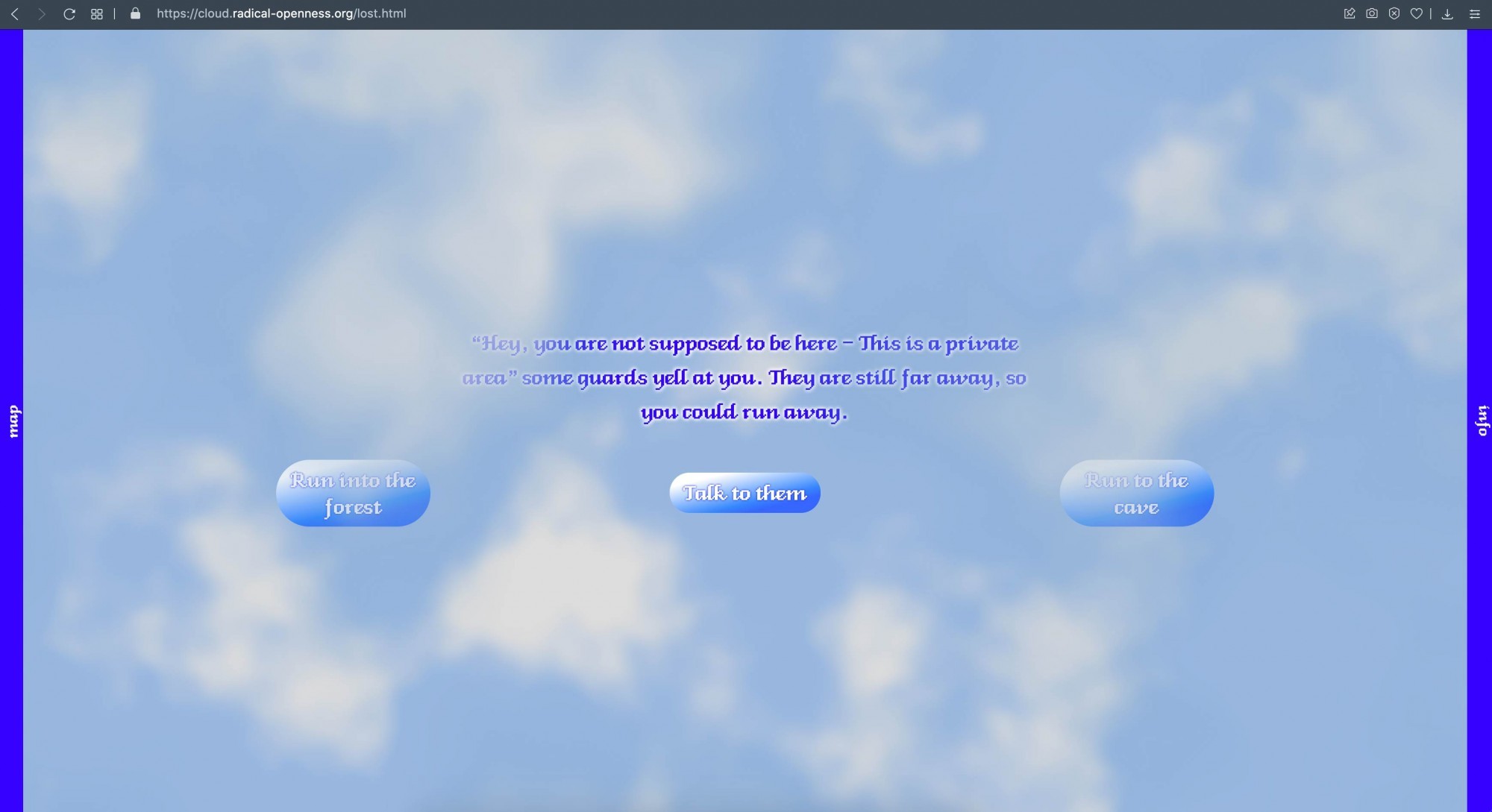

Carbon Rifts offers a critical gaze onto carbon emissions, mensuration and valuation through an experimental archaeology of wrecks. It is an art-led enquiry into forests and foreshores as salvage sites for carbon incorporating questions such as salvage accumulation,

waste management, and indentured labour. It ultimately questions the abstraction of valuing ‘nature’ by its weight in carbon.

rifts.fraud.la

Carbon Rifts was commissioned with the generous support of the London Community Foundation and Cockayne - Grants for the Art.

…

Somerset House Studios

Somerset House Studios

Carbon Rifts is an art-led enquiry which considers the ambiguity and complexity of carbon as a unit of measurement (of nature) and of abstraction. The installation offers a critical gaze onto carbon emissions, mensuration and valuation, through an experimental archaeology of wrecks. It proposes forests and foreshores as salvage sites for carbon incorporating questions such as salvage accumulation, waste management, indentured labour and slavery.

The installation questions the emphasis of the green economy on flow oriented ontologies and network structures whose systemic violence affords a tree to operate as the ultimate siphon between the exhaust of a sweatshop and climate change data banks; or in which designer furniture such as the Paimio chair can become a sleek apparatus for carbon storage, exchange or accumulation.

It contains an interface that randomly loads clips from a large database of Carbon Rifts documentation (the process of unearthing (floating) and gathering wreck wood), a "Slinger" salvaged Montague whaler wreck, a scale, a database video (indefinite length), a video loop 9'00", a wreck wood carbon value (updated in real-time) 600cm x 300cm, asphalt deposit from Pitch Lake (Trinidad) and Sperm Whale oil.

Credits:

The interface is a fork of YoHa's automaton editor.

Live carbon futures pricing was programmed by Alessia Milo, and can be found at carbonderivation.space.

Acknowledgements:

Carbon Rifts would not have been possible without the special support of YoHa (Yokokoji, Harwood) and collaboration from Belton Way Small Craft Club, Leigh Heritage Centre, Southend Borough Council, Alessia Milo, Lani Harwood, Paul Huxler, Brum, Michael Meddle, & Norman Day, among many others. Carbon Rifts was commissioned with the generous support of the London Community Foundation and Cockayne - Grants for the Art, for the Complex Value$ exhibition at the Somerset House Studios.

…

Salon Suisse

Salon Suisse

Carbon Derivaties examined the conflicts arising from market involvement in the management of ‘nature’, and the ties between the forest as a storage resource of carbon, the boreal forest’s disappearance and emission trading systems (ETS). For ATARAXIA,

…

TEA Tenerife Espacio de las Artes

TEA Tenerife Espacio de las Artes

Para que haya fiesta tiene que danzar el bosque is curated by Michy Marxuach in collaboration with multiple transhemispheric voices. The show runs from the 2nd of July to the 26th of September 2021 at TEA Tenerife Espacio de las Artes in the Canary Islands, Spain.

…

Fiskars Village

Fiskars Village

Meadow was curated by Taru Elfving and produced by The Cooperative of Artisans, Designers and Artists in Fiskars ONOMA.

…

Varvintori Square

Varvintori Square

On the occasion of its hoisting, Midsummer Mast was adorned on Saturday 29th May with a birch garland, wild flowers and medicinal herbs in collaboration with artist Lotta Petronella. On Sunday 30th May we began the collection of testimonies before the mast, inspired by the tradition of Fields of May as popular tribunals, to interrogate blue growth and the bioeconomy. This is part of an ongoing project that will continue on the island of Seili (see Fields of May).

Midsummer Mast is commissioned and produced by CAA as part of Spectres in Change project, funded by Kone Foundation. It is presented in Turku in co-operation with Forum Marinum and supported by the City of Turku. The mast was first presented in Fiskars as part of the exhibition Meadow during summer 2020 in collaboration with ONOMA.

…

Contemporary Art Archipelago

Contemporary Art Archipelago

The installation consists of salvaged discarded masts, spars and other maritime wares donated from the museum-ship Sigyn (Turku, FI), a wooden barque built in 1887 that crossed the Atlantic and Indian oceans - as well as the North and Baltic seas - for trade. As Seili is situated next to the old Baltic maritime timber trade route, where passenger ferries pass today, Sigyn routinely sailed past this island. In 2018, the ship needed new masts. Unlike last two centuries, when Finland provided most European Empires with the timber and tar to build their fleets, when scouting for mast timber in 2018, only a handful of trees were found to be of suitable size. The masts which compose the seating area bear witness to the commodification of trees, the transatlantic timber trade as much as to the changing nature of Finnish forests, now largely servicing pulp production or the blue bio-economy at large.

Fields of May is commissioned by Contemporary Art Archipelago as part of Spectres in Change, and it is funded by Canada Art Council, Acción Cultural Española, and Kone Foundation.

A

B

C

D

E

F

G

H

I

J

K

L

M

N

O

P

Q

R

S

T

U

V

W

X

Y

Z

Critical Raw Materials

Critical Raw Materials (CRMs) are resources deemed economically and strategically important for the economy of a sovereign state, and have a high-risk associated with their supply. Criticality is not derived from scarcity, but rather through the covalence between significant economic importance, high-supply risk and the lack of feasible substitutes. In the EU, this has been overseen by the Critical Raw Material Initiative (CRMI) established in 2008. The landing page of this website shows the current CRMI graph. FRAUD argues that the relationship between international relations, trade, economic policy and border security come into focus through the lens of these national resource management initiatives.

Commercial Extinction

Commercial extinction is a term derived from environmental economics that designates a decline of a resource to a level where harvesting is no longer profitable.1 It has been used marginally to explain technological succession - the eternal discussion between VHS and BETA for instance. However, it appears mostly in discussions around fisheries conservation. Species extinction and commercial extinction are related concepts—the latter often precedes the former. On the other hand, such forms of exhaustion disentangle from one another in the case of the highly sought-after Bluefin Tuna. A nearing extinction in this case drives an exponential price increase, carefully managed by the very international organisations tasked for their conservation.2 However, these modes of depletion (species vs commercial extinction) fail to apprehend the complex technosocial assemblages that saturate such phenomena.

Commercial extinctions have been embedded in many European imperial and colonial projects such as in the case of forest laws. Rules, laws, and policies directed at the conservation and management of forests were not always instituted after veritable evidences, but rather under a growing fear of resource scarcity.3 Environmental historians also remind us that the exhaustion of marine resources was one factor among many pushing sea-bound communities into fishing on deeper and further waters, across the Atlantic and through the Northwest Passage.4 Importantly also, is the fact that technological innovation and development in fishing gear had nothing to do with increasing efficiency and or performance. More often than not, the adoption of novel fishing technologies or methods was tied to the need to keep similar catch volumes as fish stock plummeted.5 In contrast to fishing communities, who often understood the complex fragility of marine environments, marine scholars often depicted the sea as boundless or immortal - outside of history - throughout most of the 19th and 20th centuries.

Commercial extinction entails death from economic, social, or cultural realms but not from the total—and virtual—inventory of marine life. That is to say, a community of organisms remain, just not enough to catch commercially. Commercial extinction is a form a “slow death” in Lauren Berlant’s terms: a “mass physical attenuation under global/national regimes of capitalist structural subordination and governmentality.”6 Such modes of extinction point toward the relative and destructive nature of capital. While commercial extinction reduces fishing grounds to mere objects of exploitation, it also shows the very exhaustion of exhaustion. It often paradoxically affords the survival of a species.7

-

National Marine Sanctuaries (2018) ‘Fisheries Glossary - Voices of the Bay,’ National Marine Sactuaries [Web]. ↩

-

Telesca, J. (2020) Red Gold: The Managed Extinction of the Giant Bluefin Tuna. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press. ↩

-

Radkau, J. (2012) Wood: A History. Cambridge and Malden: Polity Press. ↩

-

Galloway, J.A. (2017) “Fishing in Medieval England,” in Balard, M. & Buchet, C. (eds.) The Sea in History: The Medieval. Suffolk: Boydell & Brewer, pp. 629–642. ↩

-

Bolster, J.W. (2012) The Mortal Sea: Fishing the Atlantic in the Age of Sail. Cambridge and London: Harvard University Press. ↩

-

Lauren Berlant, Cruel Optimism, (Durham: Duke University Press, 2011), 95. ↩

-

Gallardo F.J.F, & Samson, A. (2018) “Commercial Extinction: the Exhaustion of Exhaustion,” in Fernandez Pascual, D. & Schwabe A. (eds.) The Empire Remains Shop. London and New York: Columbia University Press, pp. 109-119. ↩

Drago

Dracaena draco, the Canary Islands dragon tree or drago, is a subtropical tree. It is native to the Canary Islands, Cape Verde, Madeira, and western Morocco as well as to much of the scenes of the classical imaginary of the Hesperides Garden. It was revered by local peasants and its blooming fearfully observed for its forecast: "[i]f the tree flourished on the north side, the year was rainy in the highlands; if on the south, drought was to be expected. And woe to our fields when the dragon trees did not bloom! An observer noted that in 1851 all dragon trees bloomed in August - followed by the most dreadful drought on the island. However, the following winter rains were copious, which covered the coastal areas and the midlands with the greenest fields." 1

-

Rodríguez, L (1947). Los Arboles Históricos y Tradicionales de Canarias. Santa Cruz de Tenerife: La Prensa, pp. 105-6. ↩

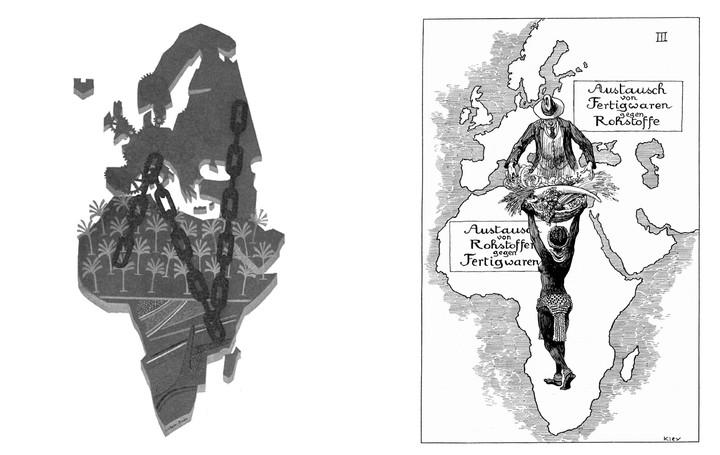

EURAFRICA

Eurafrica was (and still is) an intellectual and geo-political vehicle by which the ultimate success of the European integration project (i.e., ECSC, EEC, or the EU) was made contingent upon access to resources from the African continent. As Peo Hansen and Stefan Jonsson explain, the Eurafrican project “consolidated colonial inequality in the mid-twentieth century and perpetuated it into the contemporary world order”.1 It was conceived and articulated in the interwar period by Richard Coudenhove-Kalergi or Paolo D’Agostino Orsini di Camerota among others.2 After WWII, Eurafrica was notably problematised by France’s efforts to integrate its own colonial empire (i.e. Algeria) into the European political sphere.3

-

Hansen, P., & Jonsson, S. (2014). Eurafrica: The untold history of European integration and colonialism. Bloomsbury Publishing. ↩

-

Thorpe, B. J. (2018). Eurafrica: A Pan-European Vehicle for Central European Colonialism (1923–1939). European Review, 26(3), 503-513. ↩

-

For further information on the latter, see Samson, Audrey and Francisco Gallardo. Interview by FRAUD. “Stefan Jonsson and Peo Hansen: Eurafrica.” EURO—VISION. EURO—VISION podcast. January 28, 2021. ↩

Free Trade Zones

Free Trade Zones, Special Economic Zones, Foreign Trade Zones, Export Oriented zones, or just Free Zones are one of the many dirty secrets of modernity.1 They are enclaves carved out of national territories that are granted exceptional administrative and/or economic freedoms allowing to circumvent labour rights, environmental law and national taxation. Used as a weapon to de-industrialise occupied economies, Free Ports transformed territories into underdeveloped peripheries reliant upon resource extraction and tariff-free trade.2 After the Cold War, Free Trade Zones (arguably, resulting from the evolution of Free Ports) became a mandatory recipe and prescription from the International Monetary Fund and the World Bank to secure bailouts. Labour in these zones is disposable at "any moment, "at any moment or for any reason or hint of a reason."3 The COVID pandemic and consequent economic crisis has fuelled a mushrooming of FTZs around the world. In the UK, these newly de-territorialised areas have been heralded as the solution to the economic crisis compounded by Brexit.

-

Tazzara, C. (2018) 'Capitalism and the Special Economic Zone, 1590-2014', in Fredona, R. and Reinert, S.A. (eds.) New perspectives on the history of political economy. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, pp. 75-102. ↩

-

Easterling, K. (2014) Extrastatecraft: the Power of Infrastructure Space. London and New York: Verso. ↩

-

Bolaño, R. (2004) 2666. Barcelona: Anagrama. ↩

Fisheries Partnerships Agreements

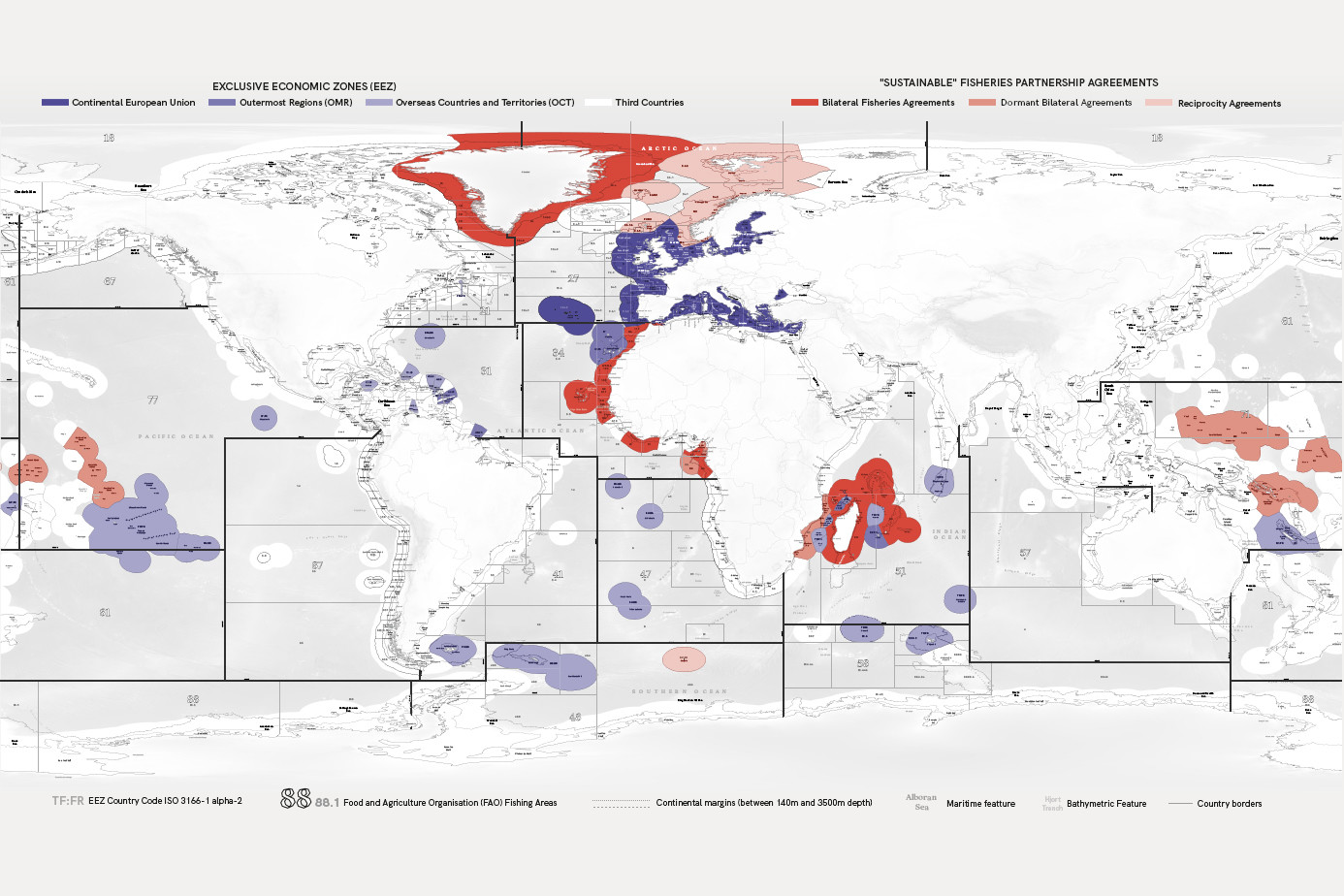

Fisheries Partnership Agreements (FPA) are bilateral agreements between the EU (which negotiates fishing access on behalf of member states) and third parties. They currently involve financial contributions in exchange for fishing possibilities as well as a contribution to partnership actions such as stock assessments, control monitoring and surveillance activities, which are broadly aligned to the EU’s Sustainable Development Strategy.1 In this way, FPAs not only govern access to water resources, they constitute an integral part of contemporary international developmental and human rights agenda.2 FPAs proliferated in anticipation of the 1982 United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS), which saw the establishment of exclusive economic zones (EEZ), severely restricting access to waters 200 nautical miles from a nation’s coast. Importantly also was the stamping by the UNCLOS of the obligation to not leave fisheries unexploited in its article 62, also known as ‘use it or lose it clause’. 3 It is through these agreements that the EU widens its sovereign waters. 4

However, these associations are often undeserving of the term partnership, 1 for as Saiba Bayo and Ernst Krose argue in the context of Economic Partnership Agreements (EPA), this is an alien word for the EU.5 The majority of FPAs are concluded with African, Caribbean and Pacific (ACP) States, former colonies of many member states. FPAs rarely include reference to the interests of small-scale fisheries sectors of the signatory country, 5 and constitute the locale for intersecting overfishing with migration. So-called ‘irregular immigration’ into Europe during the 1970s took place on large fishing trawlers.6 Nearly 80% of crews calling for Spanish fishing ports like Vigo are originally from regions in which FPAs have decisively contributed to the collapse of local fisheries like Senegal and/or Mauritania.7 The EU claims that its fishing efforts only target surplus species. In effect, it outsources pelagic exhaustion from the North Sea waters, all the while stock assessments remain to be undertaken (notwithstanding the instrumentality of such calculations for the management of extinction of species such as bluefin tuna).8

-

Mundt, M. (2012) ‘The Effects of EU Fisheries Partnership Agreements on Fish Stocks and Fishermen: The Case of Cape Verde,’ in Evans, T., Eckhard, H., Hansjörg, H., Kronauer, M., and Mahnkopf, B.(eds.) Institute for International Political Economy Berlin, Working Paper, No. 12/2012. ↩ ↩

-

Antonova, A.S. (2016) ‘The Rhetoric of “Responsible Fishing”: Notions of Human Rights and Sustainability in the European Union's Bilateral Fishing Agreements with Developing States,’ Marine Policy, 70(1), pp. 77-84. ↩

-

Campling, L. and Colás, A. (2021) Capitalism and the Sea: The Maritime Factor in the Making of the Modern World. London and New York: Verso Books. ↩

-

European Commission (2009) ‘Fishing in Wider waters,’ Common Fisheries Policy: An user’s guide, Luxembourg: Office for Official Publications of the European Communities. ↩

-

Bayo, S., and Krose, E. (n.d.) 'Los Acuerdos de Colaboración Económica (EPA) entre la Unión Europea y África: La Cara Oculta del Neocolonialismo y de las Migraciones Africanas hacia Europa.' ↩ ↩

-

Brent, Z. W., and Thibault J. (2020) ‘Migration and fisheries: exploring the intersections,’ The Transnational Institute, July 1st. ↩

-

Van den Bossche, K. and Van Der Burgt, N. (2009) ‘Fisheries Partnership Agreements under the European Common Fisheries Policy: An External Dimension of Sustainable Development?,’ Studia diplomatica, 1(1), pp.103-125. ↩

-

Telesca, J.E. (2020) Red Gold: The Managed Extinction of the Giant Bluefin Tuna. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press,. ↩

FRAUD

FRAUD (Audrey Samson and Françîcco Gayardo) is an artist duo whose work has been exhibited internationally. Their artistic and investigate practice poses questions that aim to de-centre dominant legal and policy systems validating and perpetuating resource- and commodity-oriented relations. Their current work is centred around the managerial domain of Critical Minerals (UK) / Critical Raw Materials (EU), examining how such strategies grant access, institutionalise maximum utilisation, standardise, segregate, represent difference, or uphold systems of gender and racial dominance. FRAUD aims that such effort(s) will inspire and foster different cultural practices, political imaginations, networks of mutuality and relations, and even modes of (under)world (un)making.

Somerset House Studios alumni, the duo, currently Stanley Picker Fellows, has also been selected for Artangel’s Making Time, as well as awarded the HBK Braunschweig Fellowship (2020), the King’s College Cultural Institute Grant (2018) and has been commissioned by Contemporary Art Archipelago (2022), the Istanbul Design Biennial (2020), RADAR Loughborough (2020) and the Cockayne Foundation (2018). Audrey is a professor/poètes in More-Than-Computational Arts at l’École de Recherche Graphique. Formerly an andariegos, Françîcco is an architect and geographer who was awarded the Wellcome Trust People Awards (2016) and authored Talking Dirty published by Arts Catalyst (2016). They are Studio Tutor in Architecture at Loughborough University and in Fine Art at Central Saint Martins. FRAUD’s work is part of the permanent collections of the European Investment Bank Institute (LU) and the Art and Nature Centre – Beulas Foundation (SP).

i: @la_fraud

w: FRAUD's site

Public-Private Partnerships

Public-Private Partnerships (PPPs) have been described by developmental economists as budgetary time bombs.1 Technically, they are long-term contractual arrangements whereby institutional investors and asset managers agree to finance and manage certain public services such as hospitals, highways, energy production plants, housing, or the supply of water and sewage - in so far as the state agrees to bears the brunt of some or all associated risks. It represents risk-free investment for the private investor, the risk being shouldered by the tax payer. PPPs are sometimes called Blended Investment, these have been heralded by Boris Johnson as key in attracting foreign investment. Ndongo Samba Sylla explains PPPs in further detail in Ep 3 of the EURO—VISION podcast series: Colonial Currencies and Other Investment Stratagems.2

-

Samba Sylla, D. & Gabor, D. (2021) "Planting budgetary time bombs in Africa: the Macron Doctrine En Marche," Committee for the Abolition of Illegitimate Debt cadtm.org, 14 January [Online]. ↩

-

Samson, Audrey and Francisco Gallardo. Interview by FRAUD. “Ndongo Samba Sylla: Colonial Currencies & Other Investment Stratagems.” EURO—VISION. EURO—VISION podcast. April 21, 2021. euro-vision.net ↩

Witness Seminar

A Witness Seminar is a format in which people with a specialised interest around a topic, issue of concern, or an event, gather and verbally exchange, discuss, and debate with the aim of advancing critical dialogue on the matter of address.

During a seminar, participants are invited to speak from their position of situated knowledge and experience for a short period as a means to initiate and stimulate discussion. These conversations are often chaired, and recorded. The seminar transcript becomes an archival source for future use that emphasises the capacities of interdisciplinary collaboration and embodied practice. Though witness seminars have often situated themselves in contradistinction to oral history. FRAUD proposes an interpretation that welcomes constituencies outside academia as specialists in their own right, and integrates oral history as an affirmative grounding force, while manoeuvring the legitimacy conferred through the archival form.

✕